How The Boston Globe uncovered fraud at Massachusetts nonprofits

Recently, the Internal Revenue Service made more than 2.3 million forms filed by nonprofits from all over the country available in an online database, open to the public. Todd Wallack, a reporter for The Boston Globe who has worked as an investigative and data reporter with the Spotlight team since 2013, downloaded all 2.3 million documents, organized and analyzed the data, and identified about a half-dozen charities in Massachusetts that have reported some form of fraud or embezzlement.

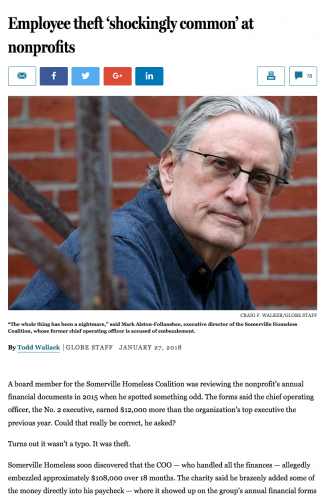

His story, “Taking from charity: employee theft ‘shockingly common’ at nonprofits” was published in late January and brought to light some of the shady behavior that’s plagued more than 1,000 nonprofits around the country.

Wallack spoke with Storybench about his role at The Globe, how the story came to be and his process of sifting through millions of electronic documents to find a story.

How did the nonprofit embezzlement story come to be?

How did the nonprofit embezzlement story come to be?

I really came into this story because I was interested in using the new IRS data. I read an item online somewhere that the IRS had recently lost a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit and was going to be required to start providing electronic versions of filings for non-profits that filed them in electronic form. Then at some point I noticed a story from The Wall Street Journal that used that data to identify people across the country who were earning salaries of $1 million or more from non-profits and that was a reminder that this data exists and, not only does this data exist, but reporters have started using the data to report stories. So, that’s what prompted me to start spending the time to figure out how to download this data and how to start analyzing other types of stories.

How long did it take you to report out the story?

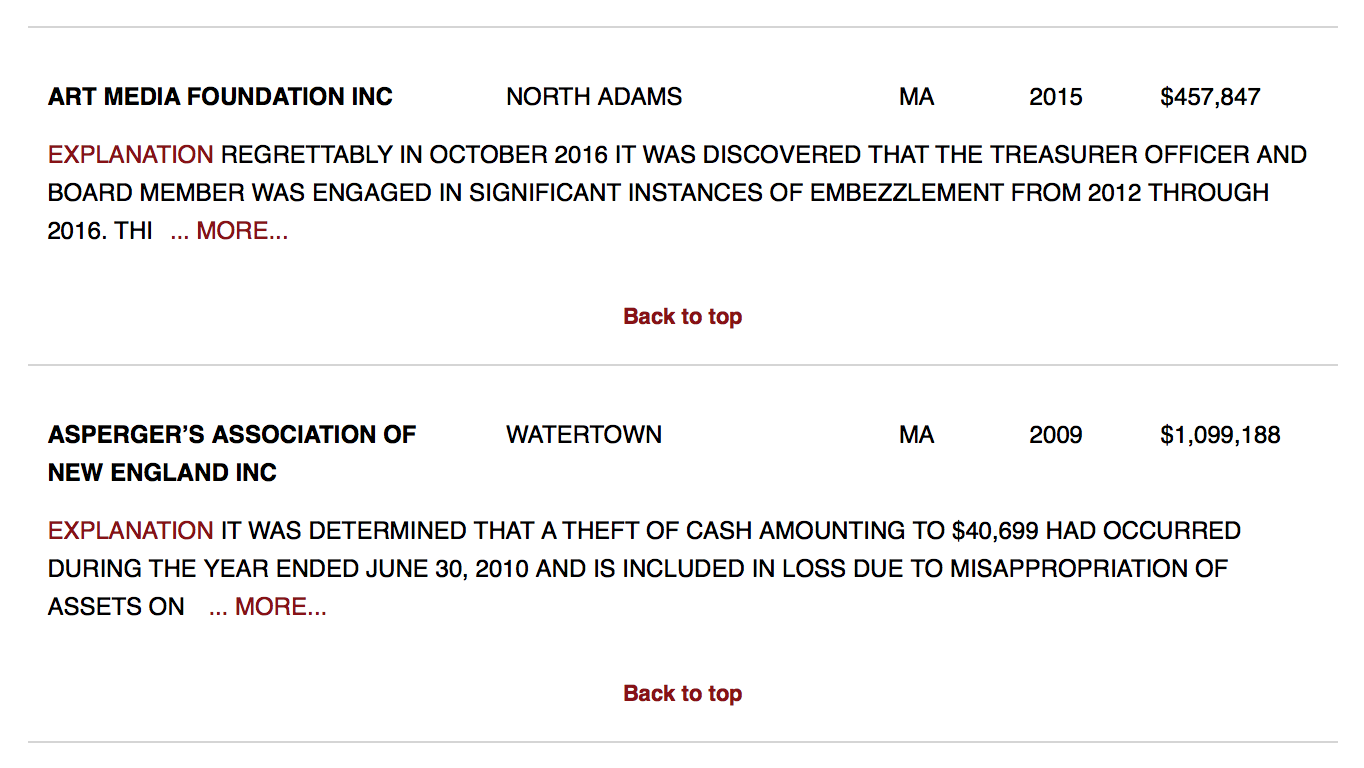

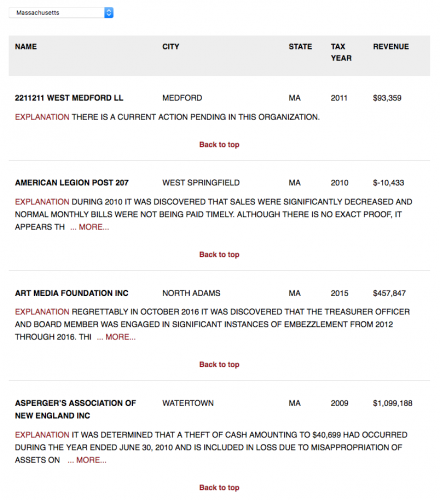

It’s a complicated answer because the story itself took me a few weeks to report and write, but it took many months for me to figure out how to download and obtain and analyze the IRS data. It took quite a while to figure out how to wrangle this IRS data and once I did, I noticed a lot of interesting things and one of the items in the IRS data is that on the standard I-90 form is a question that non-profits are supposed to answer: ‘Do you have a significant material diversion of assets?’ And I started finding a lot of organizations check-marked that form. In fact, more than 1,100 did and I was interested in finding out more and started looking at some of the cases and into some of the non-profits like Somerville Homeless Coalition that reported that they had a case of embezzlement and it had never been reported by the press, police had never arrested anyone and nobody had been convicted of a crime. So, a lot of these cases have never gotten public attention because, really, who reads all the millions of forms that non-profits file with the IRS each year?

What was your approach to telling the story? Did you want to keep it localized or present it on a national scale?

I think I wanted to take it on a national scale because the data was national and the fact is, it was easier to download all of the data than to download just the Massachusetts data because the IRS hadn’t segregated the forms into different states. They just put all the forms for each year into a giant pool that I needed to download and the program that I wrote would grab certain information from each form, including the state. So, it was only afterwards that I was able to identify which ones.

Was this a story you reported on your own or was it part of a Spotlight investigation?

It’s something that I initiated on my own. It didn’t carry the Spotlight label as a long-term investigation, but I do believe this data is very powerful and could be used for future stories. The non-profit fraud story is just one example of how the IRS data can be used to do a story on non-profits.

How often do you get to report stories on your own that aren’t part of a Spotlight investigation?

Anything that I do for print has to get the approval from my editors. I can’t just post stories on my own. Every story goes through editors. But, I’m fortunate that I’m able to do a mix of stories. I spend part of my time working with other Spotlight reporters on long-term, deep investigative work. I do pursue some of my own short-term stories and I also help people in the newsroom gather public records and analyze data.

What tools did you use to scrape data from the IRS website?

The IRS has downloaded all of the electronic forms into the cloud on an Amazon web server and I wrote a couple of different programs in a programming language called Python to grab that data. One program I wrote downloaded the indexes to all of the forms and then downloaded all of the forms themselves and put them on my hard drive. Then, I wrote a second program that went through each of those forms that I had downloaded and grabbed key information from each form and put them into a spreadsheet.

Once you had the data, how difficult was it to then analyze to decide how you wanted to present it?

Once I had the data in, essentially, spreadsheet form, it was pretty easy to identify the [charities] I was interested in. For instance, I wrote another short program that partialed out all of the non-profits that had check-marked that box knowing that there had been a material diversion of assets. So, I had all of those in a separate spreadsheet.

What was your approach to presenting the data in the story?

I really wanted people to be able to see the list of all these organizations. So, maybe if they’re in another state, I wanted people to be able to find all of the organizations in their state. First of all, it took a lot of work to find this information. Second of all, people would be curious. Third of all, since we had taken all of the time to gather the information and other people are going to want it anyway, why not just put it on the web where people can find it easily, rather than emailing me separately and my individually answering questions.

Ideally, it would be great if other reporters followed up on cases in other parts of the country that would be of interest to their readers that were not included in The Globe story because we only had room to highlight a few examples.

How difficult was it to get people to cooperate with a story like this?

“After he got the certified letter, I think he realized that I was definitely writing a story.”

Some organizations didn’t respond to calls, but I think these were all cases where organizations had already reported the incidents on their public filings, they knew I was going to write about it and I think they felt it was in their best interest to explain the situation as best that they could. One thing is that people accused of crimes or theft or embezzlement don’t always want to talk about it, so I wasn’t necessarily expecting the person accused of theft at Somerville Homeless Coalition to return my calls or email. In fact, he didn’t return email and when I called him, he hung up on me. But, I had also sent him a certified letter just to show that I had made every effort I could to reach out to him and after he got the certified letter, I think he realized that I was definitely writing a story and thought it was best to have the full context and explanation for what had happened. So, I was pleasantly surprised. [Ed note: “The problem became that I took more vacation time than I earned” was one of the explanations this source shared with Wallack.]

What tips would you have for any young reporters interested in pursuing data journalism or investigative reporting?

I think journalism can be a fantastic career and I’m really lucky that I’ve been able to do it. But, journalism can be unpredictable financially and there’s sometimes more jobs than others and it turns out that a lot of the skills that you learn in journalism and investigative reporting can be applied to many other fields. I know people who have gone into law and become great legal researchers. I know people who have gone into public relations and people who have done investigations for government agencies and other types of organizations.

So, I would urge people to keep an open mind and try to get lots of different skills because you never know where your career is going to take you. The other thing is that to be a good investigative reporter, or to be a good reporter in general, you need to have a broad background. It helps to read a lot of different things. It helps to talk to people from lots of different walks of life. It helps to be really adaptable and learn new things so all of those things are important. The last thing is, to be a good investigative reporter, it’s really important to be dogged. It’s really important to focus and work hard on something. It’s important not to give up.