Is there such thing as emoji-journalism?

As this is an ongoing debate, we’ll be continually updating this story. Please scroll down for the original post.

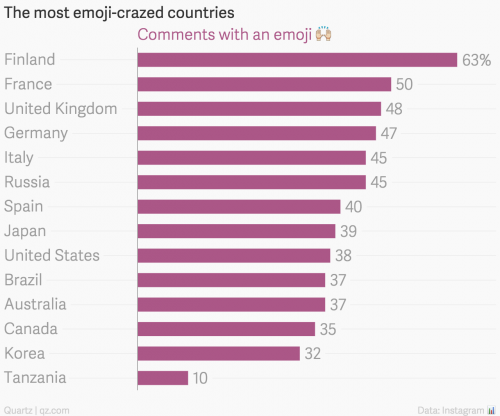

Update: July 9, 2015: Quartz recently released an app containing emoji flags of the world’s countries. On a related note, in an effort to quantify the popularity of emojis, Instagram analyzed its users’ comment threads and found that “Finland is the most emoji-crazed country, with nearly two-thirds of text containing at least one of the characters,” according to Quartz.

Update: February 6, 2015: The news outlet Fusion surveyed 1,000 millenials (18- to 34-year-olds) and found most are not okay with using emojis at work.

Update January, 2015: The Guardian published the 2015 State of the Union address in emoji form.

@Journalism2ls @storybench Of course there is: @newsinemoji.

— Martin Hoffmann (@martinhoffmann) January 21, 2015

https://twitter.com/basilesimon/status/557968270163058688

Our original piece:

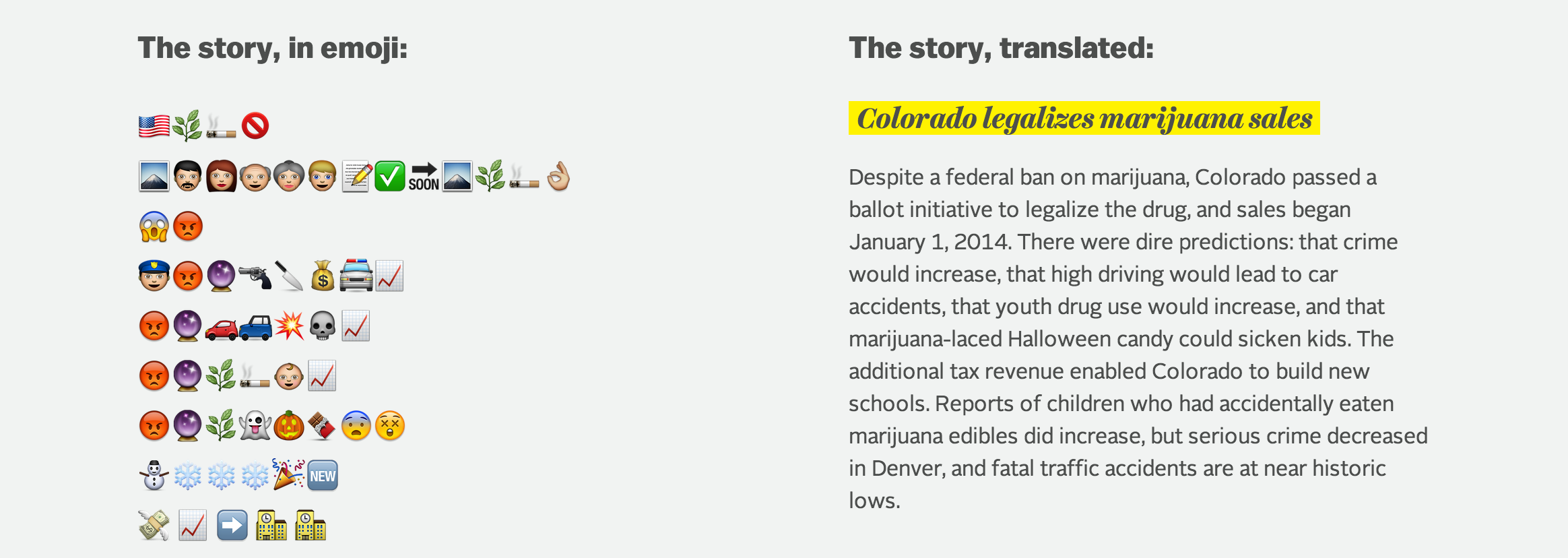

At the end of 2014, Vox did a roundup of the year’s biggest stories told in emoji form. It’s worth a glance.

We noticed the debate earlier in 2014 when outlets were targeting millenials with emojis. “We’ve covered a debate using emojis,” boasted Billy Penn, a mobile-first local news platform in Philadelphia (they borrowed the idea from Boston.com). Billy Penn, started by The Washington Post‘s former digital guru Jim Brady, targets a millennial audience. Emojis are part of a strategy to get to them. Older folk may not understand these 21st century hieroglyphics, but young folk do.

Brady argued for emojis on November 13 in the Columbia Journalism Review:

“The inverted pyramid works for some stories, but certainly not for all,” he said, describing Billy Penn’s style. “So we’ve covered a debate using emojis, and are doing a weekly Spotify playlist based on the Philly news of the week. Both went over well with the audience.” (Emoji are a recurring theme: the site also aggregated editorial endorsements from around the state by summarizing them in emoji form.)”

But some journalists are up-in-arms about the use of emojis.

“The reader of news should be reading words, not symbols,” writes Kim Hyatt, who polled the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors about the use of emojis in journalism. Jimmy Bellamy, of the Duluth News Tribune, told Hyatt this:

“Emojis have a place in communication, texting and social media, specifically, but I don’t see them as something that will or should creep into journalism. Smiling and frowning faces long have been used to convey emotions in writing, even before computers. And with the growth of technology, the symbols, too, have increased. But they should be kept as a brief, seldom-used tool rather than a replacement for the written and typed word.”

Still, outlets like Marketwatch and Vox have embraced emojis. The New Yorker is perennially writing about them. And New York Magazine recently published an emoji-heavy piece about their vocabulary and their rise as a tool:

“They’re simple. They’re silly. They don’t yet have a taco. But they work, at least a little, at least right now. We blow each other kisses. We smile with hearts in our eyes. We cry tears of joy. We say “I love you,” but in a million different ways, each one freighted with the particular meaning we hope fervently to convey, then send them out hopefully, like a smiley face in a bottle, waiting to be received by the exact person it was intended for, and opened up, and understood completely.”

I think it’s safe to say we’ll see journalists continue to experiment with emojis, their only limit being dexterity–both manual and institutional.

Comments? Tweet us or leave your comment below.