“The Immigration Experience” humanizes the history of immigration law. Here’s how.

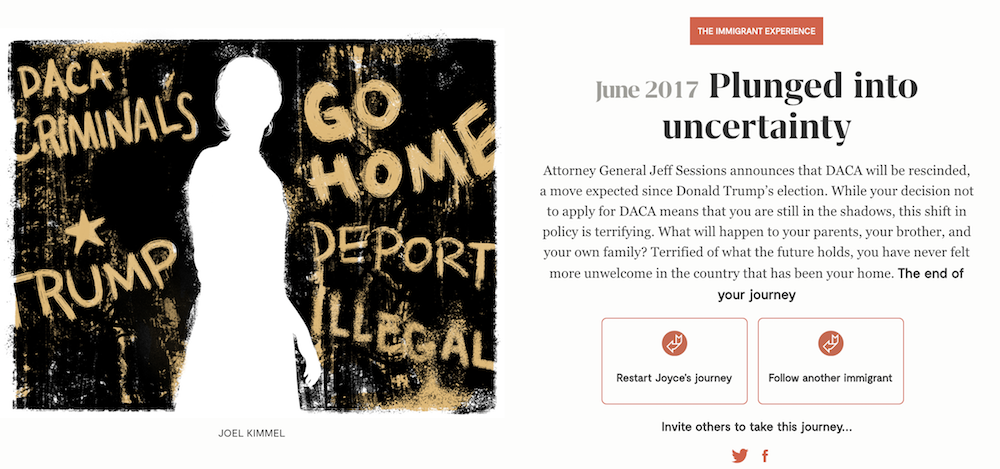

After the Great Famine, you leave Ireland for America. When anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant sentiment peaks in Boston, do you stay or move to Lowell? Or maybe your parents bring you from the Philippines to Chicago, where you grow up undocumented. The time comes to apply for a driving permit; do you use a fake ID?

“The Immigrant Experience” from Experience Magazine is an interactive that lets you follow eight composite characters, from various countries and time periods, through the twists and turns of U.S. immigration law as it pertains to passage, family unification, and paths to citizenship.

Storybench sat down with project leader and designer Dan Zedek, a Professor of the Practice in Northeastern’s School of Journalism, to discuss how he and his team created this immersive, choose-your-own adventure way to tell the immigration story.

This experience reflects the history of immigration law and experiences throughout history, from Irish Margaret in the 1800s, or Hamid from Iran in a post-9/11 climate, to Joyce as a DACA Dreamer. What was the process like to create these eight composite representations?

The idea behind Experience Magazine is to show transformative power of people’s lived experiences. The way to illustrate what it feels like to be immigrant – and how that’s changed in this country over time – was to let users actually engage with the hard choices immigrants face.

We found that the law and social attitudes toward immigrants have changed over time. For instance, the experience of someone coming from Ireland in the nineteenth century versus in the 1990s is dramatically different. So, we worked with a historian of immigration, Gráinne McEvoy, and created composite characters for users to follow that show those changes.

Speaking of the team, you’re the first U.S. citizen of your family, and the team members all have personal immigrant stories. How do you think this shaped the project?

When we started putting the team together, I was just chatting with the editor Joanna Weiss when I noted how everyone on the team has their own immigrant story – as almost everyone in this country does, I suppose. And she was the one to suggest including the brief immigrant bios on the methodology section of the piece.

I’m not sure if it shaped it, but I’d say we were all moved by the resonances and echoes of our own experiences. Two of us are in the process of becoming citizens now, so it is particularly interesting to them.

For me, it made me think a lot about my parents and what things were like for them. They had a very positive experience, but it’s interesting to look at how immigration looked like at that point in time.

How was this first conceptualized? Did your intent change along the way?

The project took about three months, with a fairly intense last month.

I had done the initial design for Experience Magazine, which launched just in the fall. I loved working with that team, and they invited me to create some immersive experiences in a more experimental form. I came back to them and pitched a bunch of different ideas with different techniques, and I’m very curious about the possibility of using techniques of gaming (trying not to use the word “gamification!”) to let people control their experience and live their own adventure. I knew I wanted to apply that gaming technology to the immigration story.

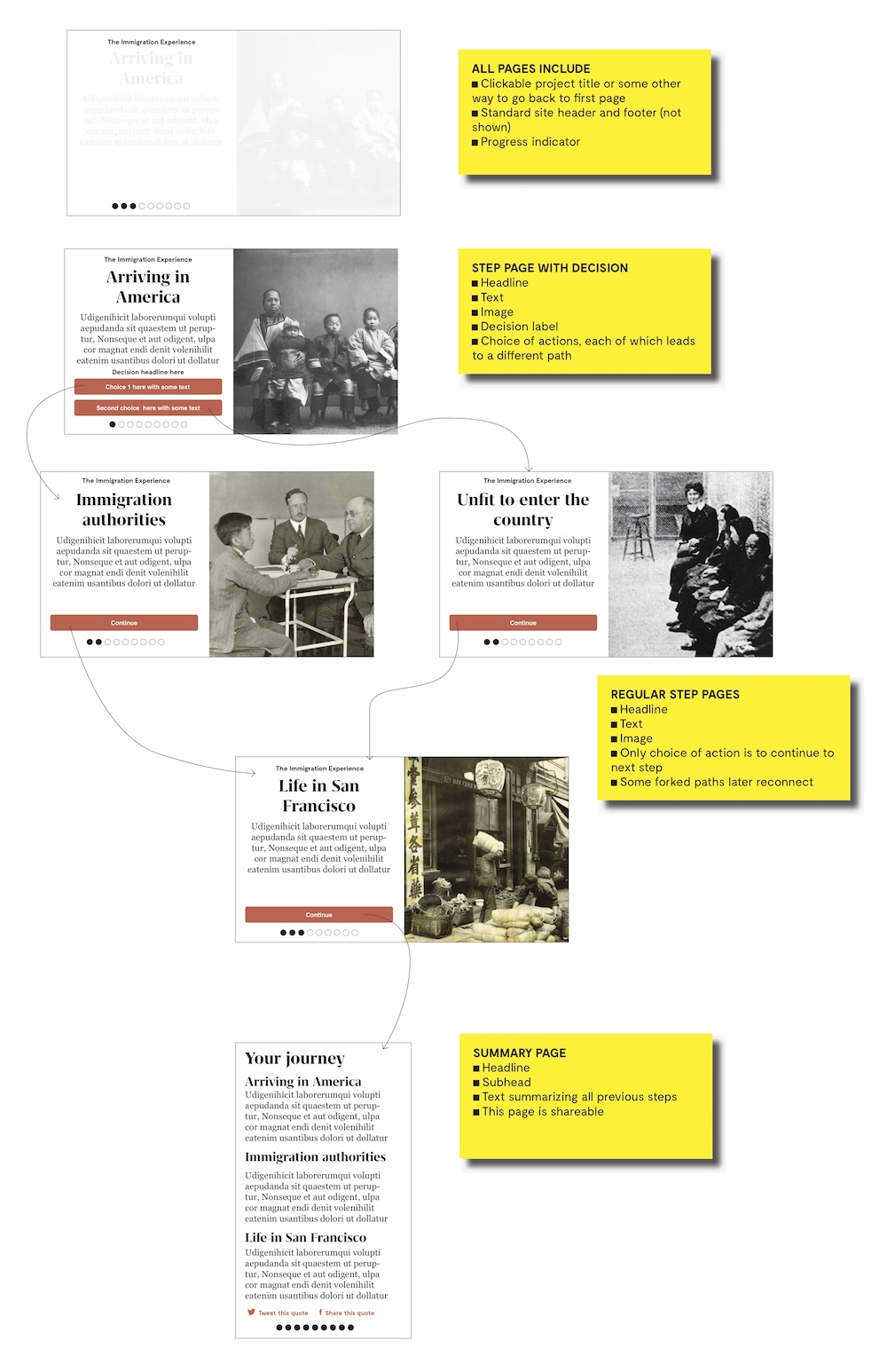

A real turning point, a seemingly small thing, was when Experience designer Mike Workman looked at the draft and had the suggestion, “What if we told these stories in the second person?” This shift in narration had a real impact in user testing — people were more invested in the story when the choices framed around “you.” One of the most gratifying things is people who have said they’ve taken the adventures over and over to play out the dozens of possible paths.

Another source of inspiration has to do with my wife working with Global Boston, which is a digital project chronicling the history of recent immigration to greater Boston.

I also spoke with Sisi Wei of ProPublica’s “The Waiting Game,” to discuss her strategies behind telling five different interactive stories of people or families being granted asylum in the United States. (Storybench also sat down with Sisi Wei to learn about the project here). That piece is a little different, however, in that they use actual historical figures, is in the third person, and doesn’t force users to make choices. Ours, on the other hand, tries to really put users in the shoes of our composite characters in more of a “choose your own adventure.” Both approaches have a certain kind of power.

How else did user testing impact the project?

User testing was fairly informal, but pretty widespread. We would mock up one story and have people take it without being given any instructions. Then we asked them how it worked, what they learned from it, how it made them feel. We were playing around a lot with that idea of “gamification,” and seeing how involved people became.

We identified some things to get rid of; for example, we chose to drop a feature where you could sort of “level up” with animations, indicating if you made a “right” choice. Some other choices involved taking away the “gaming” feel in order to maintain an appropriate tone. We wanted to strike a balance between navigating the story through a game-like feel, but upholding a journalistic tone rooted in empathy.

The testing was also very instructive when we were looking for things like text length and wording, how to pull people in, how the visuals should interact with the text.

What other design considerations went into the project?

We wanted to have a sense of forward motion, of making choices. It became more game-like as we went along. There were a lot of subtle things. The links where you make choices look more like game buttons now, with their little icons for different choices, like love versus money, strife versus security, or education versus family. We tried to make those choices more pointed. We found that we used a sense of motion a lot, like the subtle animation in between slides that was added in the later design to give people a sense of moving through time and progressing the story.

We also have things at the bottom like a progress bar, where even though your journey can be very different lengths depending on the choices you make, it gives you an approximate sense of where you are. Some stories have 8 steps, some have 15, but no matter what, it emphasizes that you’re in forward motion and making progress.

We also got rid of choices that ended up not feeling like choices at all. We wanted real forks in the road: do you stay with the woman you love, even if it means you might not be able to return to the country? We wanted the decisions to feel real.

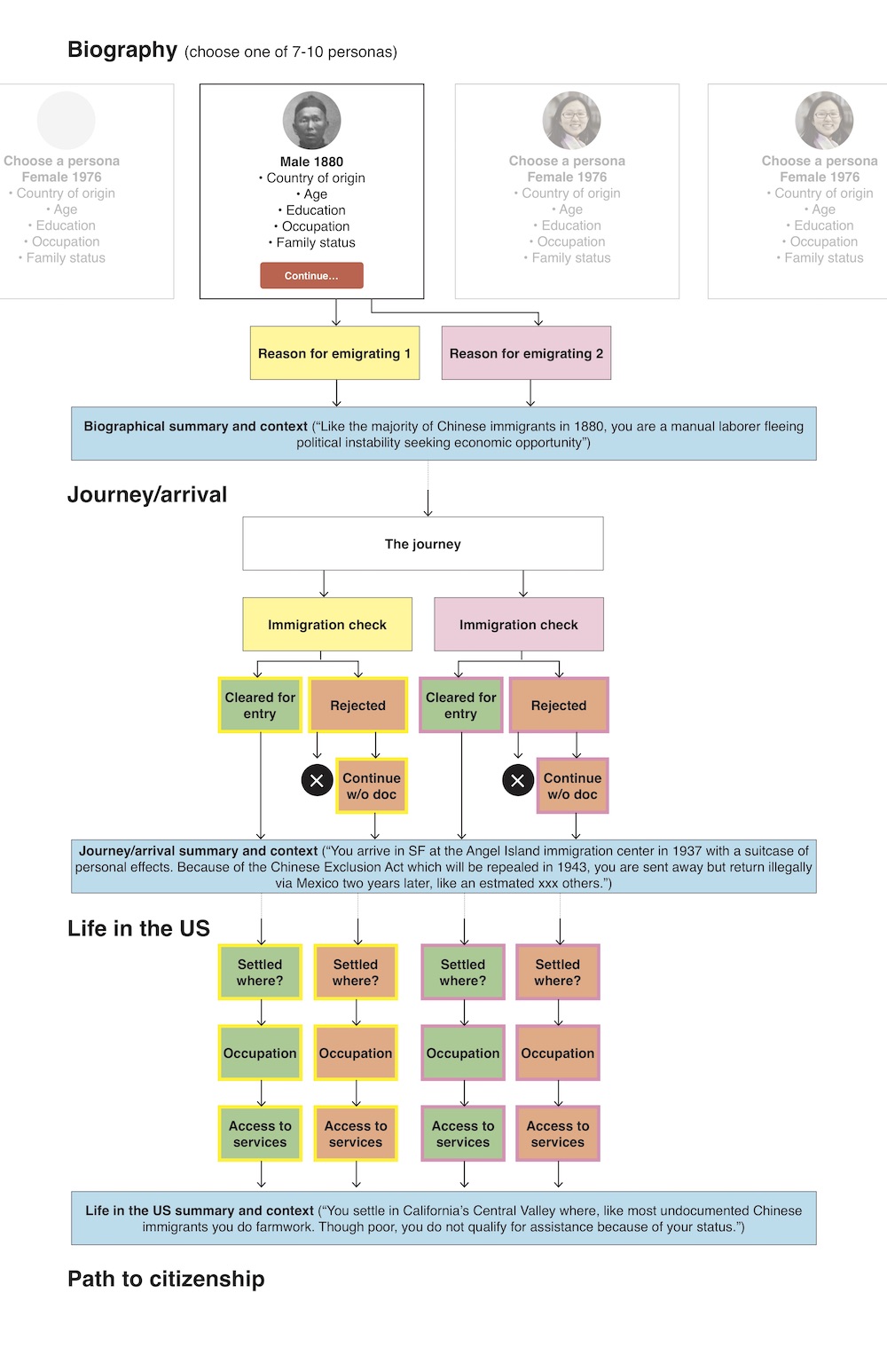

Considering all of the possible options, what did the planning look like for constructing these different paths?

The first sort of skeleton for this project looked at all the turning points in people’s lives and immigrant’s lives generally speaking. So almost every one of these has the backstory of the place where you start, how you got there, what you brought, what you faced entering the country is common to all of them. Then there are themes of family, work, social norms, conflict around all of those. So we started with eight fairly parallel stories, and as the composites progressed we saw them diverge.

What was the biggest challenge?

Finding the right stories that were representative of these eras and the choices people faced.

Gráinne McEvoy was brilliant, she started with a bunch if laws and then found stories that illustrated how these laws affected people. Interestingly, she didn’t start with people – she started with policy. I think then the challenge was putting flesh and blood on what these policies did to people’s lives.

What was the coding process to create the interactive experience?

Yan Wu, the backend developer, wrote in to respond to this question:

The story used the enhanced starter template created by Russell Goldenberg at The Pudding. This template uses Google Doc and ArchieML, a markup language which can convert text to a formatted data structure, as a micro CMS. It allows the reporter, editor, coder and designer are able to work on the same Google doc, make fixes, add comments or even assign tasks. Once changes are made, instead of copying and pasting changes in the index.html file, I just needed to run some script to make updates. Goldenberg did a From Start to Finish tutorial on how he created a data visualization project using this template.

No matter how many storylines there are, the logic behind the project is simple: each button is a link that directs the user to one slide. After experimenting a few methods, I decided to depend on window.onhashchange, a web API that is widely supported by different browsers. When a button is clicked, it broadcasts a message to notify every element of the web page that the hashtag is changed. So all the javascript code needed to do is to attach some info to this message like “Hey div with this id, it’s your turn to display. Everyone else, please hide from the viewport.”

The biggest challenge is to make it responsive to different devices. I mainly used CSS Flexbox, a well-supported CSS module to lay out, align and distribute space among items in a container and relied on many media queries under the hood. CSS libraries bootstrap also seems an easy solution for creating responsive pages. But understanding vanilla CSS is a must as you need to constantly overwrite the CSS when those libraries restyle the webpage in an unexpected way.

What common thread connects each of these eight immigrant stories?

It’s the human common threads: work, love, family, belonging to and building a community.

Another common thread that may surprise people who haven’t studied immigration is the myth that immigration is a uniform thing that hasn’t really changed throughout history, when in reality, it has transformed dramatically and constantly throughout history. Just think of the decades where Chinese couldn’t come, or the bracero program where Mexicans were encouraged to come in a sort of limbo between citizen and laborer. Things have changed, and the changed we’re seeing now echo the restrictive times we’ve seen before. They’re driven by the same concerns as from earlier eras.

Who is your intended audience, and how did that inform your choices?

The intended audience is pretty broad. We were thinking about people who don’t necessarily know about immigration, or people who know a little about the current circumstances. But almost everyone in this country has an immigrant story. And there’s two very obvious groups that don’t have immigrants stories: people brought here as slaves, or the few who were here when Europeans first arrived. Almost everyone else in our audience can connect to an immigrant story in some way.

This project is being published right before midterms. How would you like this to resonate with voters right now?

We did consciously publish this before the midterms, because immigration is such a hot topic and giving background to how we got to where we are is of service, no matter how you feel about it. That being said, it turns out to be incredibly timely, like with one of the characters, Yesenia, arriving in a caravan…it goes to show that immigration law resonates in daily life.

We don’t tell users how they’re feeling. The language is toned down to present the facts, and users can draw their own conclusions about what the immigration experience would feel like.

What do you think is the most powerful part of your experience?

We’re still in the early stages of analyzing metrics, but anecdotally, so far it looks like people are spending a lot of time with it. They’re trying new characters and returning to try a new set of options with one character. In a world where staying with a story for two minutes is unheard of, it’s really engaging people.

I think the most powerful part of this experience is that it takes something abstract, immigration policy/law, and lets you see these hard choices in flesh-and-blood terms. That’s the beauty of the project, and if it’s successful, it’s successful for this reason.

- How The Pudding visualized the structure of Ali Wong’s stand-up comedy - February 7, 2019

- “The Immigration Experience” humanizes the history of immigration law. Here’s how. - November 9, 2018

- Behind the scenes with Galen Druke and FiveThirtyEight’s Politics podcast - October 30, 2018