Journalists improve coverage of memes with careful reporting

It was the moment memes are made of.

“Who is this 4chan person or website?”

CNN anchor Brooke Baldwin made the fatal mistake of not knowing what 4chan is. Her guest, CNN tech analyst Brett Larson, didn’t help, describing 4chan as maybe “a systems administrator who knew his away around and how to hack things.”

It was 2014 and 4chan, an anonymous internet forum known for its lax rules, had just released a massive number of nude photos of female celebrities in an event that would soon be dubbed “The Fappening” (fap is an internet slang word referring to masturbation).

Media coverage of internet culture in general and memes in particular has often been terrible, and “the hacker known as 4chan” meme is the apotheosis of that failure.

Memes are cultural artifacts found primarily on the internet. The modern use of the word “meme” originates from Richard Dawkins’ “The Selfish Gene,” where a meme is defined as a discrete unit of gossip, knowledge, jokes, and so on; the cultural analogue to a gene. This definition of meme, and its corresponding field of study, memetics, is rarely used in modern contexts, which instead refer to internet memes, internet-based jokes that come in a variety of media.

Memes traffic in familiarity. They combine pop-culture references, internet slang, and in-jokes. Over time, memes take on a life of their own. They become pop-cultural mainstays, create their own slang, and become templates and references for future memes. In this way, memes spawn their own culture: meme culture.

It’s no mystery as to why media often gets memes wrong. Meme culture is notoriously impenetrable to outsiders, by design, as many of the most popular memes originate from the most insular corners of the internet. When meme culture was covered by mainstream media in the past, it led to blunders so infamous they remain well-known to this day, best exemplified with “The hacker known as 4chan” segment.

“When journalists only superficially report on memes, they don’t go anywhere,” said Myojung Chung, an assistant professor of strategic communications at the University of San Francisco. “Instead, journalists should provide the broader context behind the memes as well as look into the wider implications of them.”

Coverage like CNN’s, which failed to report on the surrounding details of the phenomenon and instead speculated based on only the most basic information: that photos were stolen and posted on the web. By doing this, Chung said, CNN only contributed to spreading the harm the hack created.

Reporting on internet memes isn’t just about explaining them to an audience that doesn’t understand them. It’s also about not becoming a part of them.

2015 and 2016 were odd years for Luke O’Brien. An assignment to report on then-presidential candidate Donald Trump morphed into a safari through the fever swamp that would soon become known as the alt-right.

The fruit of his labor, “My Journey to the Center of the Alt-Right,” published in the HuffPost on Nov. 3, 2016, is a deep dive into a subculture that went from tiny fringe to household name in a matter of months. And it all began with a failed assignment.

Shortly after Trump announced his candidacy, Politico Magazine hired O’Brien to write a ride-along piece about the campaign. Hope Hicks, the campaign’s spokesperson, refused to allow O’Brien anywhere near the president unless he was willing to pay up – $30,000 for a single flight on Trump’s private jet, for example.

“As I was trying to come up with plan B to salvage the Trump story I noticed, just doing some basic background research on the campaign, that quite a few far-right extremists were endorsing the Trump candidacy very early on,” O’Brien said in an interview.

O’Brien’s goal from the outset was to immerse himself in the world of the alt-right. He began browsing 4chan, The Daily Stormer and the seedier parts of Reddit and taking copious notes. Over time, O’Brien said, he began to see prominent figures emerge in the movement. His eventual piece would focus on three young leaders from different corners of the alt-right world.

Getting people like Richard Spencer, a self-avowed “white nationalist” who coined the term alt-right; Andrew Anglin, founder of The Daily Stormer and notorious internet troll; and Matthew Heimbach, heir apparent to David Duke; was easy – the figureheads were desperate for the attention and legitimacy of mainstream coverage. The difficult part was sifting through their nonsense.

“These guys are all pretty media savvy, and they’re all looking to use the media and I’ve seen a lot of credulous reporters engage with them and platform their views,” O’Brien said. “All they really want is to have these ideas circulating in the public consciousness, to expand the Overton window, as it were.”

The Overton Window of Political Possibilities, often simply referred to as the Overton Window, refers to the range – or window – of political policies that are considered acceptable enough for a politician to pursue them. To shift or expand the Overton window is to alter what’s policies

O’Brien, an investigative reporter, found success with a “just-the-facts” approach. If he couldn’t substantiate a remark or easily disprove it, he wouldn’t report it. This also gives the piece a somewhat humorous tone.

After Matthew Heimbach complained that the supposed diversification of his hometown had destroyed the interconnectedness of the community, O’Brien found that, over the past decade, only 22 non-white people had moved into the town. “He was probably as close as he was ever going to get to his homogenous high-trust society,” O’Brien wrote.

O’Brien’s work also heavily incorporated memes, an important part of alt-right culture. Only after months steeped in the web’s cesspools did he began to see patterns emerge in the seemingly random postings.

“There’s a lot of toxic material, you’re processing a lot of crap, basically, a lot of it is nonsense,” O’Brien said. “But, if you immerse yourself, you start to see connections and you start to see these pathways for disinformation to move closer to the mainstream.”

It was much easier to follow those pathways from the outside in, O’Brien said. Writing about a meme alone isn’t doing it justice – you need to write about the ideas and people who express themselves through the meme, and the best way to do that is by talking to people.

“Pepe the frog is the obvious example everyone points to but it’s a pretty good one because it’s something the average American would have no idea about three years ago.” O’Brien said. “The story isn’t that this innocent cartoon frog is somehow a hate symbol, it’s the path it took to become the de-facto mascot of the alt-right.”

“It was Anglin who elevated Nazi Pepe from 4chan and made him a presence on The Daily Stormer. The ecosystem did the rest,” O’Brien explained in “Journey.” “In October, Trump retweeted an image of himself with the face of Pepe standing behind a presidential lectern. Later, the Anti-Defamation League declared Pepe a hate symbol.”

While the fact that meme culture is so omnipresent in modern society may make it seem like an obvious choice to grant it coverage, the implications of playing into a meme’s virality must be considered. John Carroll, a media critic, warns of extending the life of objectionable content.

“I don’t think it necessarily has to be covered. Just because some graphic or some meme takes off on social media, doesn’t mean it’s worthy of wider circulation,” Carroll said. “This about giving an afterlife to a certain type of content.”

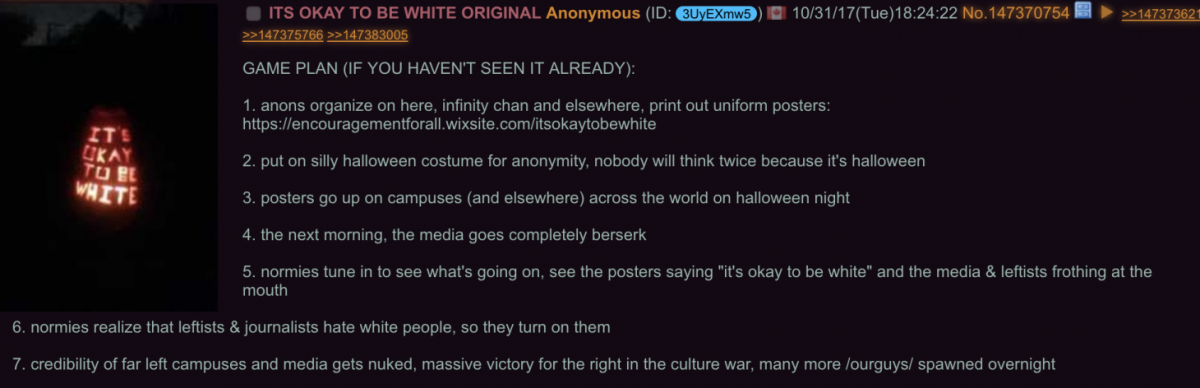

Indeed, the phenomenon of using seemingly innocuous memes to provoke criticism is part of a common alt-right tactic sardonically referred to as “meme-magic,” as O’Brien points out in “Journey.”

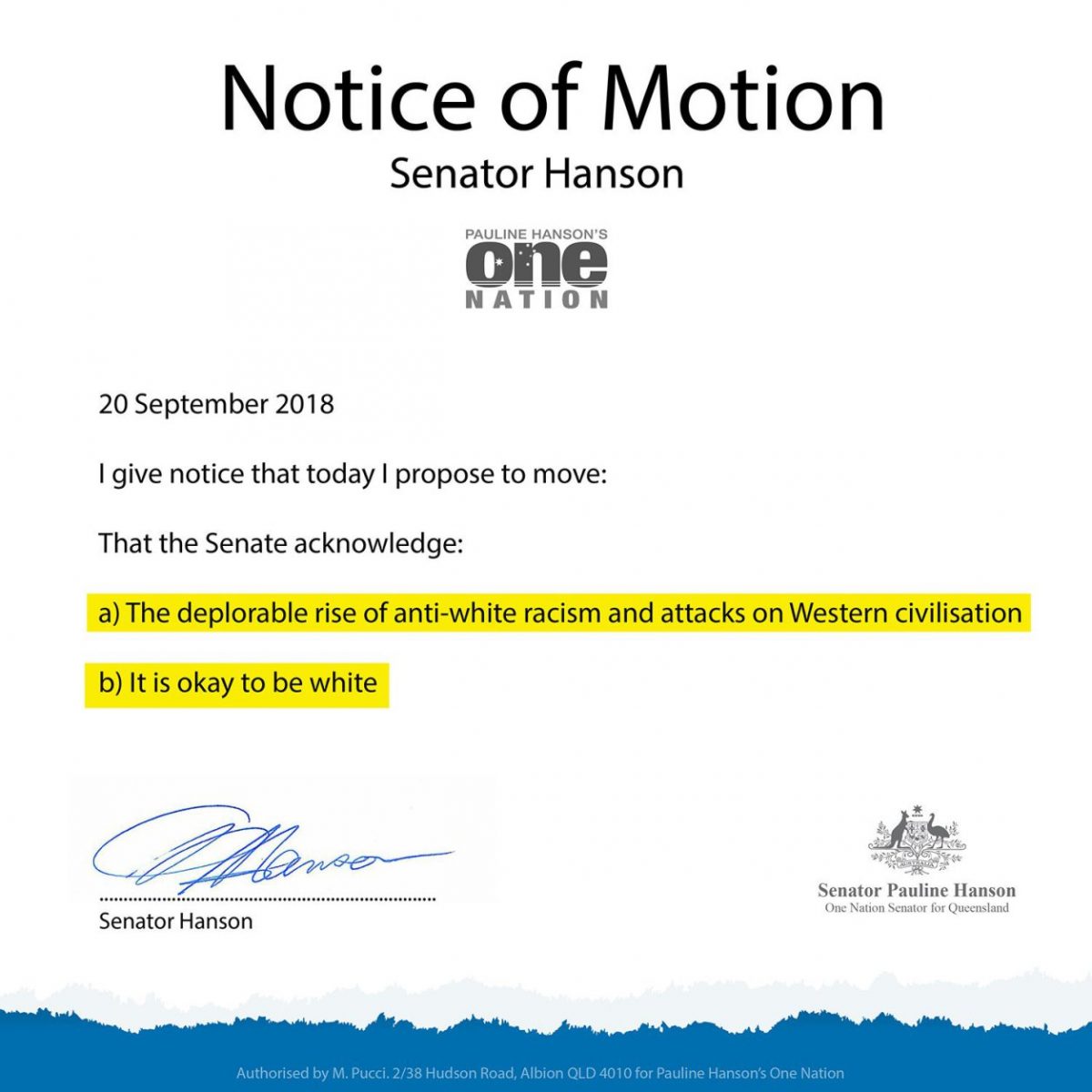

Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon is in the “It’s OK to be white” campaign, which reached its zenith in Australia earlier this month when the Senate voted for a motion put forward by Senator and right-wing provocateur Pauline Hanson declaring as such and decrying “the deplorable rise of anti-white racism and attacks on Western civilization.”

The campaign originated on 4chan as a tool to paint left-wing groups as out of line, as an Australian Broadcasting Corporation story revealed.

“They’re trying to wedge their political opponents. Somebody says, ‘It’s OK to be white, don’t you agree?’ If you say, ‘No I don’t agree’, oh well what — so you’re against white people?” said Dr. Kaz Ross, a lecturer in global cultures and languages, in that article. “And if you say I do agree, they say, ‘Oh OK, then so basically there’s no such thing as white privilege and that white people can be treated badly like minorities.”

Another common issue is in taking things too literally. Mathew Ingram, chief digital writer at the Columbia Journalism Review, believes that memes must be viewed through a critical lens.

“I think the risk with any subculture, but particularly memes, is there’s often kind of a performative affect to them. In particular, on places like 4chan, things are done ‘for the lulz,’” Ingram said. “You need to look at them as a kind of performance in front of one’s peers that may not be something they believe deep down.”

It’s also important to debunk any disinformation found in memes. This was especially problematic in the 2016 election, said Tish Grier, a freelance journalist social media expert.

“Find the source, show where it came from, or show that it is untrue in another way,” Grier said. “All memes have sources and many of those sources aren’t hackers, so blaming hackers for memes is merely scapegoating one group.”

Covering memes isn’t the same as covering other pop-culture phenomena. Simply reporting on observations isn’t acceptable, according to Chung, the communications professor.

“I believe journalists should take memes more seriously to understand why and how people use memes to engage in politics,” Chung said.

In other words, memes demand serious, comprehensive reporting, and the only way to achieve that is by immersing oneself completely in the subculture they wish to understand.

- Journalists improve coverage of memes with careful reporting - December 19, 2018