Storytelling in sports: how mic’ing up football players brings a human element to sports broadcasts

“This is what we were made for right here,” Russell Wilson, the Seattle Seahawks quarterback told his teammates during a huddle on the final drive of this year’s Super Bowl.

“Let’s get it. Come on.” It was a classic sports pep talk, words to pump up one’s teammates. But Wilson wasn’t shouting. He sounded nervous, hesitant, as if not entirely sure his team would score the one touchdown they needed to win.

A few breathtaking plays later, the Seahawks had the New England Patriots backed up into their end zone. Seattle had mere inches to go to win the game. But in a call that will go down in football infamy, Wilson threw a risky short pass right to the goal line. Patriots cornerback Malcolm Butler, a rookie player, intercepted the ball.

“Oh no!” shouted Pete Carroll, the Seahawks head coach, throwing down his headset. The Patriots players rushed the field. With only seconds remaining, the Patriots interception won them the Super Bowl. Dazed, Butler walked back to the sidelines surrounded by cheering teammates. “You won that game, man,” Patriots defensive end Chandler Jones told Butler. “You just won us the Super Bowl, man.”

For the entirety of Super Bowl XLIX, a total of nine players and coaches were wearing wireless microphones and being tracked by video cameras. That footage was edited into a riveting seven-minute episode for a weekly series called Sound FX that is part of NFL Films, the documentary and film arm of the National Football League. Mixing live audio recordings with video from the field and stands, Sound FX tells the story of a football game by focusing on the humanity and raw emotions of the players and coaches. The Sound FX episode of Super Bowl XLIX’s waning minutes has so far attracted 400,000 views.

Since its founding in 1962, NFL Films has won 117 Emmy awards. One of those Emmy‘s was in 2010 for a Jets versus Bengals Thanksgiving game for ‘outstanding live event turnaround,’ meaning the producers edited the game time footage into a tight story for airing only hours away.

“I believe we had 16 wires between the two teams, wires in the coaching booth, hidden wires everywhere,” Shannon Furman, a producer with Sound FX and NFL Films told Storybench. The game was being recorded on a Thursday night for broadcast on Saturday night which meant Furman and her team of eight had to work fast. “Footage was being driven back from the Meadowlands [the Jets stadium in New Jersey] in cars. We divided the game up into eight different parts and turned it around in 24 hours.”

Furman took Storybench through the process of recording and editing a Sound FX episode. After NFL Films producer Ross Ketover works out with the teams which individual players and coaches will be recorded, sound engineers travel to the football stadium about five hours before the game starts to meet with the teams’ equipment manager. A lavalier mic is installed on the top of the shoulder pad and is encased in foam padding and tape. Because the installation happens hours before the players suit up, many times they forget they’re being recorded, Furman noted. This helps leads to getting charged emotion on tape.

Catching human details

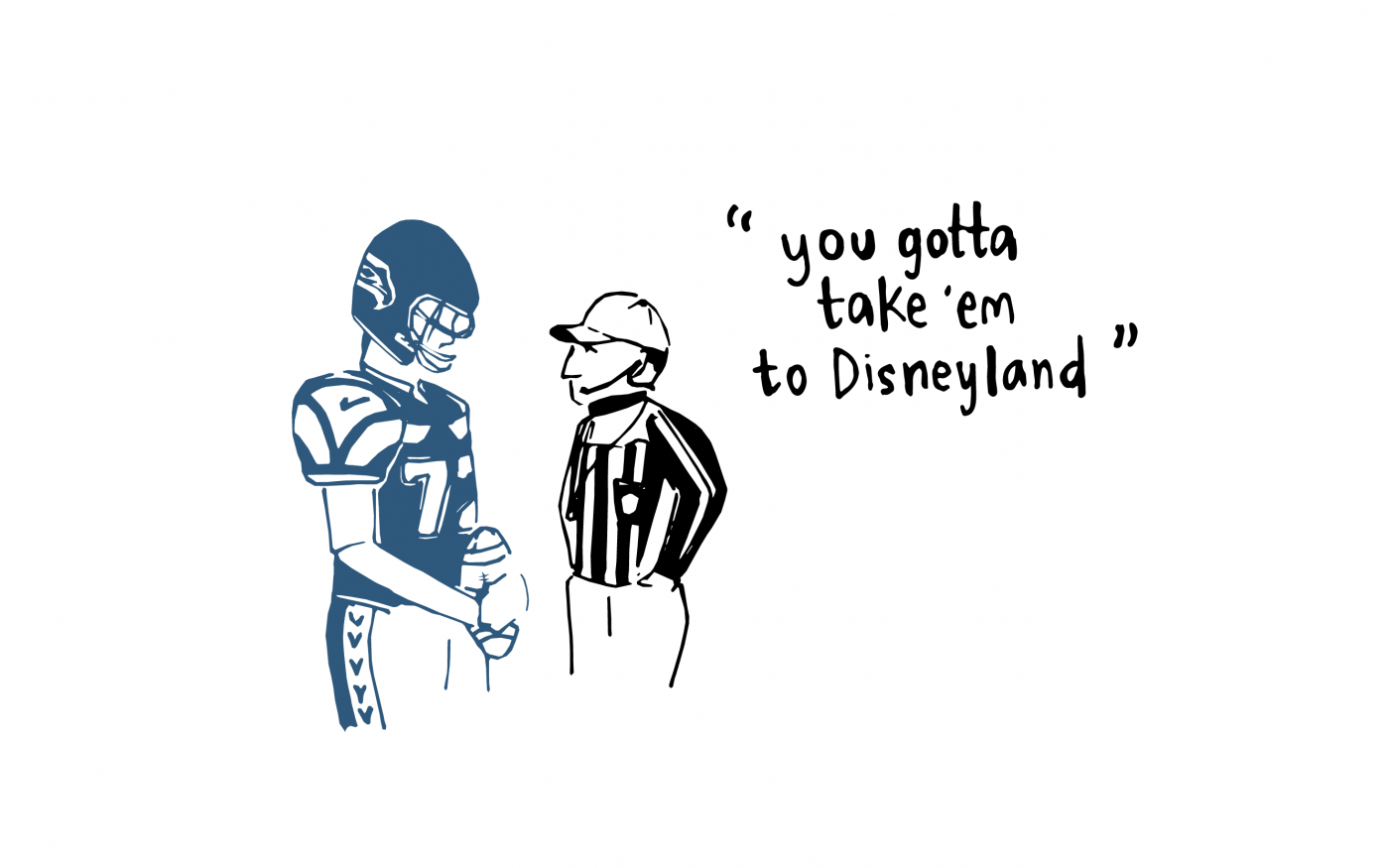

The audio that Furman and her colleagues are recording are the details that until now, viewers would miss. They offer a window into the world of sports — the pep talks, excitement, disillusion, and lots of humor, whether deliberate or not. The exchanges between players and referees are particularly interesting.

“Seventy-six is hands to the face every time,” said Michael Bennett, Seahawks defender during this year’s Super Bowl, complaining about an illegal move. “I got three kids, right? I got three kids. I love my kids. I love my daughters. I wanna play with them after football, but you gotta call it both sides, man.”

“You’re right. How old are they? How old are the kids?” asked Bill Vinovich, the sympathetic referee.

“My kids are eight, three and one,” responded Bennett.

“You gotta take ’em to Disneyland,” said Vinovich.

“I gotta take them everywhere, but I can’t do it if he keeps grabbing me by the face, man,” Bennett answered.

Choosing the right players

Sound FX tries to record specific players because they know they’ll provide interesting commentary, said Furman. “We love [Tampa Bay Buccaneers’] Gerald McCoy, his wires are always great.”

Other favorites of Furman’s include Indianapolis Colts quarterback Andrew Luck, former Oakland Raiders head coach Dennis Allen, and Houston Texans defender J. J. Watt.

“Make sure you have a good view. Get some popcorn,“ Watt told his teammate before a game against the Tennessee Titans last month, predicting a great game for himself. Sure enough, that same game he sacked a quarterback, stripped the ball for a turnover, and then came in with the offense and caught a touchdown pass.

Though this year’s Super Bowl had nine wireless microphones, during the regular season, NFL Films deploys four wires per week, to be distributed among the games. If it’s an important game during the season, NFL Films will deploy five or six microphones. The number of cameras sent by NFL Films to record games roughly follows this pattern, too.

“Every week has at least two cameras. The top two or three games get a weasel camera, too,” says Furman. “That’s the camera that’s essentially telling the story of the game without shooting football. It’s shooting fans outside the stadium, it’s climbing up in the rafters, it gets the shot of the [airplane] flyover.” Five or six games also have a sync camera that are told always to follow the mic’d players and coaches so NFL Films has synchronized video footage for a given sound clip. As for the types of cameras? “We’ve been testing cameras since I got here in 2004,” said Furman. “We’ve been testing the Red camera, the Alexa, all sorts.” They currently use ARRI Amira’s and Panasonic 3100’s.

The editing process

Once all the audio and video for a game is recorded, Furman and her team start organizing the footage. These days, audio and video footage is uploaded from the stadium. They no longer have to drive the cards back to the NFL Films headquarters in Mt. Laurel, New Jersey, just outside of Philadelphia.

“Every producer is assigned a section of the game and we log that section,” she said. “We have different terminology for different types of scoring, for different plays. We have a starring system for the clips that must be in the show. Usually we have one or two clips that have to make it in. Those get four stars. If a clip gets one star, the shot should be looked at.” By Monday morning, all the footage from the weekend’s games needs to be logged in the system.

To edit the episodes Furman uses Avid, software for audio production. There’s no strict formula to the way a Sound FX episode is edited. “Producers have a lot of freedom,” she says. “We score our own segments, I choose my own music.” Because microphone access to players and coaches is so unique, Furman prefers to let this ‘game wire’ tell the story. Other producers may use more play-by-play commentary from radio announcers.

When the sequence is finished, Furman sends it to the sound mixers for the finishing touches. “We call it sweetening,” she said. “They make every sound clean and think of things that I would never do. Every year they win an Emmy.”

The legacy of Ed Sabol

One cannot write about storytelling in sports broadcasting without talking about the creator of NFL Films, Ed Sabol, who passed away this week at the age of 98. A World War II veteran, Sabol experimented with film in the 1950s and in 1962 decided to try and film the Super Bowl. He put in a bid for $5,000 for the filming rights, which in today’s dollars would be more than $30,000.

The bet paid off. Impressed with his work, the NFL asked Sabol to film all of their teams and bought his production company. NFL Films was born and with it many of the storytelling devices that are now ubiquitous in sports broadcasting: the slow motion shot, the extreme close-up, the booming voice-over, and, of course, microphones on the field.

Simply put, Sabol revolutionized the way we watch sports. NFL Films and shows like Sound FX continue to use new technology to bring sports broadcasting to a higher level.

I appreciate reading stories like these.

I do have a question though, what kind of wireless lavalier mics are they using on the players?