How the Center for Public Integrity is using surveys to report on tick-borne illness and climate change

With the northeastern United States on the brink of summer, bug spray will soon be flying off the shelves as hikers, bikers and others prepare for adventures outdoors. But, inevitably, for many those treks will mean encounters with ticks. And you may have noticed an up-tick in news coverage of ticks in the past few years – namely, that it’s happening earlier in the season, for longer stretches of time, and in more extensive regions in the United States.

Late last week, the Center for Public Integrity tweeted out two surveys about tick-borne (and mosquito-borne) illness, marking the start of a large project and story series on the health impacts of the changing climate. The first survey asked those affected by tick-borne illnesses to share their stories dealing with these diseases and to answer a few questions related to their understanding of ticks and mosquitoes as vectors for transmission. The second survey asks health professionals who are already looking at the expansion of these diseases to help CPI quantify their costs and consequences.

Storybench sat down with the project’s lead reporter, Kristen Lombardi, along with CPI’s audience engagement editor, Nesima Aberra to chat about what CPI wants to know about Americans’ understanding of tick-borne and mosquito-borne illnesses, their effects, and their relationships to climate change.

What initially drew you to the topic of health and climate change?

Lombardi: I started looking at the human health impacts of climate change in 2017, in a series of stories we did around the build-out of natural gas infrastructure in this country and its implications for climate change. I had come across a number of physicians who were talking about the real health impacts of climate change. They were looking at the impacts of fracking, in particular, and the pollution that tends to arise out of the extraction process. But, they were also beginning to talk about how this infrastructure was going to contribute to and worsen climate change, and that the health impacts tied to the physical changes happening in the environment are because of global warming. I had never really heard people discuss the health impacts of climate change, so I began to really look into and read a lot of materials on these various impacts. With human health, the agencies typically reviewing these impacts are the CDC and the EPA. The National Institutes of Health, with its various centers, also funds research.

Given that there are so many potential indicators for the impacts of climate change – more frequent hurricanes, droughts or just other disease vectors like rodents – what made CPI decide to assess tick and mosquito-borne illnesses?

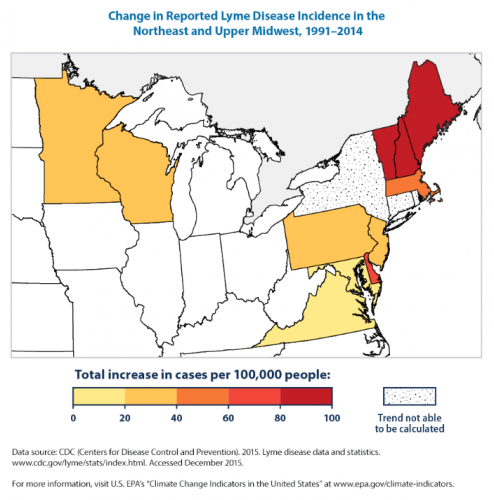

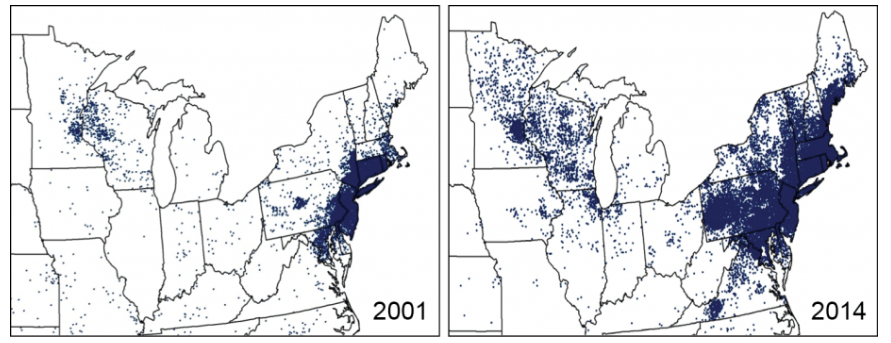

Lombardi: With vector-borne diseases, I started talking with a lot of researchers, beginning with a 2016 report, and spoke with those that offered the chapter on this topic, and it turns out that in 2014, the EPA made Lyme disease an official indicator of climate change. This is because the expansion of the deer tick, followed by increased onset of Lyme disease, has been substantially linked to a changing environment. It’s been moving northward and there has been quite a lot of research correlating this expansion to rising temperatures. There’s also been quite a lot of research showing aseasonal activity in the tick-season, because of these rising temperatures happening during the winter. That’s sort of why I became interested in it in the first place, it was because of this correlation.

“In 2014, the EPA made Lyme disease an official indicator of climate change.”

Now, the EPA has also named the spread of West Nile Virus as an official indicator for climate change, so there’s obviously mosquito stories and then there’s tick stories. But, I’ve quickly realized you can’t cover everything as a reporter, and getting [your story] from the science alone is very difficult [hence the public survey]. We were interested in Lyme disease because of this sort of EPA connection and our talks with researchers at the CDC, and then in Canada, because the country has just seen a huge explosion in Lyme and subsequently in the deer tick population. We started to look at ticks, because they were getting more attention than mosquitoes and mosquito-borne diseases, especially when it comes to the connection to warming temperatures.

Can you give us an idea of the scale and scope of this problem with regards to the expansion of ticks and subsequently Lyme disease?

Lombardi: It’s not just Lyme disease. It’s also kind of these rare tick-borne diseases babeisiosis and anaplasmosis [these attack the red and white blood cells, respectively] that are also rising. And they’re rising like this because the same tick carries them, though not nearly to the level that Lyme is reported to be. Lyme is complicated because it’s also expanding southward. There are other factors that kind of confound this climate connection. It’s not solely related to warming temperatures, because the disease itself is and has expanded south since 2000. Those areas were already hospitable to the tick. This means that there are other factors at play, like changing land use, for example – urban sprawl where people are now living closer to forested areas where the tick thrives. But what was compelling was the explosion in both the tick population and the number of cases in the northern-tier states and into Canada, where the tick and Lyme, before, virtually did not exist, even in the 1990s. It’s really been since 2000. And, in part, I’m looking more specifically at Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Vermont, northern New York, and Michigan. Those states, if you look on a county-wise basis and at the incidence rate, they’re really seeing a surge of cases – not just of Lyme, but also of the rarer tick-borne diseases – in the last five years. It’s really phenomenal.

Why look at cases within the last decade? Was there a specific reason or strategy to look at this specific timeframe?

Lombardi: Well, the number of cases have really soared (albeit, it’s been a little more than in the last decade). I’m looking in counties in Maine for instance, where the incidence rate per capita has, since 2010 when the census came out, has ballooned 729 percent, 435 percent, and 213 percent. And if you look at cases alone, there are counties that have jumped 7500 percent, 6710 percent, 5280 percent. That’s a huge explosion of cases recently. And this isn’t over decades; rather, this is in six years. And that’s just in Maine. We’re seeing similar numbers in other northern-tier states like Minnesota. Moreover, when you look at rising temperatures, that’s also when we start to see this correlation more clearly, during this century.

“You want to put a human face on the statistics that you’re writing about.”

Lyme diseases has existed since the 70s, but there’s been an acceleration that’s very recent. That’s why we want to get people to answer the survey if they’ve been swept up in this explosion, if they contracted this disease during this time. Not necessarily people who were sickened in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, when it wasn’t at epidemic proportions. It’s kind of like you want to put a human face on the statistics that you’re writing about, the ones that matter most. And so we focus on this timeframe because, as I said, we wanted people during this explosion of cases, who are a part of these statistics.

How do you see this story as a reflection of CPI’s mission?

Lombardi: It’s dereliction of duty if the government agencies that are taxed with protecting people’s health are not allowed to look at this issue, due to the political dynamics surrounding climate change. A huge part of our story is what the government agencies at the local, state, and federal levels are doing to identify the human health impacts of climate change and prepare for it. Many many public health experts have described the human health impacts of climate change to me as, ‘the biggest public health crisis facing the country.’ But because of the politics around climate change, there are large numbers of agencies that aren’t able to actually tackle this.

There are plenty of health departments that I’ve come across expressing they feel they can’t use the words, either because their governor or their legislators don’t think climate change is happening, and so have passed bans or edicts that say you can’t use the terminology.

“There are some states where government employees are not allowed to talk about climate change.”

State and local governments talk about the health impacts from the physical changes in the environment that are happening, but can’t mention the words ‘climate change.’ How can you talk about them, if you can’t talk about climate change? How can you prepare citizens if you can’t talk honestly about it? It’s actually a question in our survey: “are you actually allowed to use the words [climate change]?” It’s a question for health department employees: “Do you think it’s important to use that terminology?” Are governments making that connection, and if they are what kind of interventions are they doing that may be different than in the past, because they’re making this climate connection? And that’s why we have a second survey that really focuses on health professionals to try and gage awareness and action. The whole genesis of this came from talking with doctors and nurses, so we’re looking closely at their analysis of this connection. There have been past surveys done by professional associations, like the National Association of County and City Health Officials, for instance, as well as the Medical Society Consortium of Climate and Health. They’ve done surveys on communities, but not for a while.

How might you try to visualize this information going forward?

Lombardi: Our developer scraped through all of the nationally notifiable disease data. So, not just Lyme disease, which I was able to get from the CDC pretty easily, but all the tick-borne diseases and all the mosquito-borne diseases over time. He’s then looking at marrying that with climate data – temperature data, precipitation data, etc. We’re still deciding what kind of maps, what kind of graphs we want to use to show this.

The Lone Star tick has been described to me as even more of a climate indicator. It’s always been based in the southeast, but is now inching northward and now has been found established in northern Indiana, Iowa, New York and the Long Island area (because I’ve spoken with people there). The question is, can the tick survive if the climate becomes hospitable enough? The Lone Star can spread different kinds of other diseases that may not be nationally notifiable, because they were just recently discovered. I mention in the survey, ‘alpha gal syndrome’ [which causes an allergy to meat], for example. Our developer is looking at ways to visualize not just the spread of Lyme, which is a big part of our story, but he’s studying modeling papers on Lone Star ticks and mosquitoes – especially the mosquitoes that carry Zika virus and dengue. We want to know how scientists model the spread of the disease, in order to forecast expansion based on a warming climate.

Is there any future for this data as far as sending it back to some of these health professionals you’ll be talking too?

Aberra: For a lot of our projects, we’ve kept the data open. We really want people to use the tools that we create to help them with their reporting and help them (if they’re a public official) with their constituents in understanding a particular issue. I’m not sure yet what we plan to do with the data we get from these surveys. They’re obviously going to be included in the series – so Kristen will reach out for follow-ups, so that people can be quoted in a later story. Some of the health professionals we gather data from may not all be talking to each other about the same issue, even though they’re working in the same field, so we’re hoping that this is a project that people can mobilize around as a conversation-starter. I’m not sure that we have a targeted partner at this point, but we’d like to find different kinds of partners that would help add different elements to the story. So, whether they do a video piece for us, or something on the radio, we’re really open to engaging people in various ways about this topic. We’re hoping that people who are close to this topic, and also those who don’t know anything about it, can find a reason to read the story and pass it on. This is something that affects everyone, but everyone may not know about it!

What wisdom can you offer for journalists looking to do surveys of this scale on other stories relating to the health impacts of climate change?

Lombardi: You should think of surveys as a reporting tool. Having done enough preliminary research, you need to know what it is you’re trying to measure and whom you want to cull that information from. That helps you shape your survey.

“You should think of surveys as a reporting tool.”

It’s always helpful to try to talk to experts who might be social scientists or at least have thought about how to measure this in a scientific way in the past. They can help you devise the right questions so that the information you’re getting is what you want to get. Secondly, think about ways to get the survey out to people. This survey is not as socially scientific as some other surveys that we’ve done.

Aberra: Everyone is bombarded with stories every second and surveys like this are very easy to ignore. So, if you want people to take that extra step and take action, it needs to be very clear why they should do it and what it is they’re looking for. When you have that in mind it helps you to focus the creation of your survey. I think it’s important to also understand the gatekeepers. How do we find these people that we want to hear from? They’re not all already following you [or your organization] on social media or be on your email. Really understanding who you’re trying to target and why will help you think about where you would find them, whether it’s online or in person. The last thing is really thinking about what are you going to with the contributions that people give you. I think it’s important not to start a project and then totally forget to acknowledge where this is going to go, letting people know what’s going to happen. If they contributed, it’s about letting them know if they are ever going to hear from us again. It’s about making sure people understand we’re not just using that for our work and for our story.

Update: This article has been updated to correct the spelling of anaplasmosis.

- Emily Atkin is pissed off about climate change. Her new newsletter Heated says we all should be - October 1, 2019

- How to grow your brand as a photojournalist and commercial photographer - August 1, 2019

- Six digital skills all new journalists should consider learning and a road map to unlocking them - July 15, 2019

I have been told that native American turkeys are a strong predator of ticks in general. Is this true?

Hi Anna! Thank you for your question! I believe turkeys have been considered a viable vector for ticks. I would say probably no more than deer or other larger fauna in the northeast though.