How the Financial Times used narrative game design to illustrate the lives of Uber drivers

As media outlets continue to experiment with innovative forms of digital storytelling, some journalists have turned to the lucrative video game industry for inspiration.

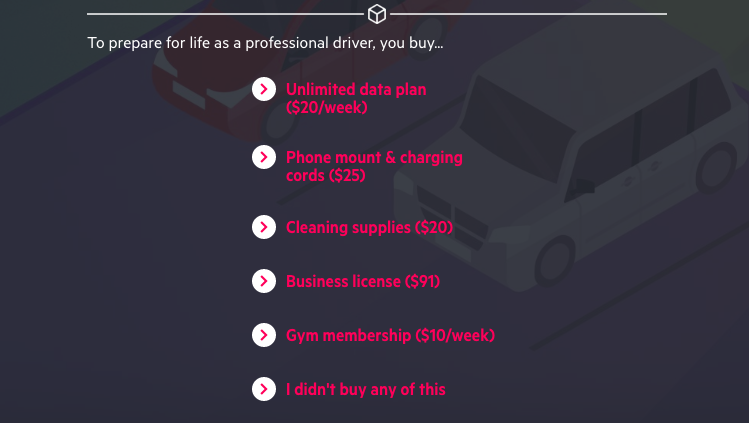

Last year, Financial Times released The Uber Game, a “choose your own adventure” interactive program that offers players a glimpse into the day-to-day lives of full-time Uber drivers. To create the narrative behind the game, the reporting team spoke to dozens of Uber drivers about their experiences working for the Silicon Valley giant. In addition to the game, Financial Times published an in-depth article that takes a more detailed look at the challenges faced by employees of the ride-sharing group — and how Uber execs are trying to remedy the situation.

Storybench spoke with Robin Kwong, head of digital delivery at Financial Times, about the inspiration behind the game, the reporting and development processes, and the role of interactivity in digital journalism.

How was this story first conceptualized?

The story was first conceptualized as just a desire to do a new game. I used to be on the interactive news team, and at the time I was the special projects editor [at Financial Times], and so a lot of what I was thinking about was: What are the good uses of interactivity in journalism? It was also around the time when the broader journalism, data visualization and data journalism community was moving away from interactivity. I had felt like, at the time, that while that was good – and that was a needed trend in what we were doing – it also felt a little bit restrictive. I felt like there must be something more that we could do with interactivity. Games and game design felt like a direction that was really interesting and not very well explored, so I was really interested in doing that.

For a long, long time it was just a technical idea in search of a story. Just before December 2016, one of our reporters at Alphaville did a series of stories on Deliveroo in London. She did a whole series of articles and posts about Deliveroo, primarily around the deliverer. That sparked the idea, initially, that actually what we’d have in the post is one description of one playthrough, but you could generalize that, and you could make a game around that. That was actually the original idea, but that really didn’t work for a variety of reasons. It went on hiatus for a little while, but it was always in the back of my head. I had the opportunity to go to San Francisco for three months as part of this internal fellowship that the Financial Times has, and I was talking about this to Leslie Hook, our correspondent who covers Uber. It matched with her interests, because she had been covering Uber for a long time, and she really wanted to find ways to write about the drivers. She’s also interested in trying out new forms of storytelling, and that’s how we ended up coming together and coming up with the idea that became the game.

Was it always pitched as having the game with the traditional news piece to accompany it?

No. It was originally just the game, but because Leslie had to do so much reporting, and she had so much stuff in her notebook, that it seemed like a bit of a waste not to use some of the other stuff in the notebook. Also, I think as we got a little bit further on in the project, it became a little bit more clear what the game is good for and what it’s not good for. There are certainly aspects of the story that were much clearer and much easier told through the article, which explained a little bit of the broader context and what specifically Uber is doing. It would’ve been hard to shoehorn it into a game.

How long did it take to report out the story?

I would say roughly three months. It was not completely full-time and continuous, so Leslie was doing all sorts of other stuff in the meantime. It was also probably impossible to have condensed that and done it all within a continuous period of time because there was a lot of iteration, trial and error.

When you were looking for sources, was there an emphasis on looking for a diverse pool of Uber drivers?

We thought a lot about where the game is set. We initially thought maybe it should be generic, or we would be able to use location-based services to say, “We detect that you’re in Minneapolis, so this game is set in Minneapolis.” But what we actually found while reporting is that the situation differs vastly from city to city. It’s just really different economics depending on the different cities. We decided to just focus on San Francisco as a result. Then, we thought about whose stories we wanted to tell. Are all Uber drivers basically the same, or is there one particular set of stories that we wanted to tell? We decided that it was most compelling to tell the stories of full-time Uber drivers. These are only about 10 percent of the total number of drivers, but because they drive full-time, they account for more than half of all the rides, of all the miles.

Because of the nature of that job, the demographics also became quite clear. Actually, when we were doing the illustrations, initially the brief I gave to our illustrator was, ‘Here are the scenes.’ We didn’t really say anything specific about it, and she drew a young white male, and we were like, ‘Actually, you need to draw the driver differently, because 90 percent of the people we interviewed were not moderately well-off, young, white males.’ They were actually migrants. They were new arrivals to the States, almost entirely male. So they had a pretty clear demographic profile.

What was the coding like to create the game?

There were two parts to it, basically. One was: What do you use to script the game? Basically, it’s like a ‘choose your own adventure’ game, which means there’s a branching narrative. Depending on what your choices are, the narrative branches off into different directions. We needed a way to write all of that, and also to manage all of that. Then, once you have the content management system, and whatever that spits out, there’s also another really complex bit of technology around how you display this. How do you put it on a website? How do you get it to link to the other Financial Times stuff? How do you get it to function properly on both desktop and mobile?

On the content management side, how do you actually write this game? I looked at using Twine initially, and then I looked at using Ink, which is the one that we ended up using. It’s an open-source tool with pretty good documentation for how to use it. I did all of the tutorials, and then I just followed the instructions.

What are the benefits of using “choose your own adventure” style games to tell these types of stories?

A traditional article is like, ‘We have already preselected all of the information you need to know,’ and it’s very one-way in the sense that you, as the reader, just sit there and absorb all of it. I think using this ‘choose your own adventure’ type of thing, or using interactivity in this way, the biggest thing that it does is it allows us to place readers or players into the shoes of someone else, and, in a well-designed game, they would have to make meaningful choices – with consequence – as they play through. This activity of really having to think about what choices to make and making those choices hopefully helps generate empathy, helps to make them curious, helps to make them go, ‘Huh, actually, I didn’t even realize that choosing the right type of car makes a difference. Now, I have some questions about this whole thing.’ They get curious, and they want to find out more information.

What challenges did you face, from conceptualization to publication?

For me, the biggest conceptual question to try to answer with this was: Is it even possible? Is it an oxymoron to say that there is an interactive nonfiction? Is this still journalism, or is it not journalism? You can have different results depending on how you play through the game, and inevitably, you get into hypothetical situations when you go through some of these choices. I think, fortunately, we ended up achieving that quite well, but that was definitely a difficulty and an open question throughout. The other thing, of course, is that this type of writing – scripting, making choices – is a really different type of writing. I don’t have any background or training in narrative game design so a lot of it was learning from scratch.

You mentioned earlier how you came up with the idea for this game back when journalism was moving away from user interaction. What role do you think user interaction can play in digital journalism?

I think it’s good that we are overall being much more careful and deliberate about how we use interactivity. Certainly, this sort of backlash is needed because back then, it came in response to people being overly enthusiastic and saying that everything should be interactive. What that leads us into is a world where we’re a lot clearer as to what interactivity is good for and what it’s not good for. I think what it’s good for is personalization. It’s almost impossible to do personalization if you don’t have any form of interactivity or code-driven journalism. Being able to look at an election results story and not just see who won, but also to go to my district and see who won in my district, that’s important. Another is “test your knowledge” type stuff. The third thing is games, and specifically, what that is good for is explaining rules and systems. In this case, the Uber game turned out very well almost coincidentally because Uber’s whole design of their system is very game-like, and a lot of Uber drivers approach their driving in a very game-like way. The format really seemed to fit the story. I think revealing the shapes and the truths and the effects of different types of systems is a really good use of this type of interactivity.