How NPR used voicemails to explore national grief 20 years after 9/11

Every year, the anniversary of 9/11 comes around again, and news organizations are left wondering how to cover it in a way that has not been done before. Twenty years after the attacks, NPR found an innovative method of telling a story of national grief and exploring what that grief is like for those left behind.

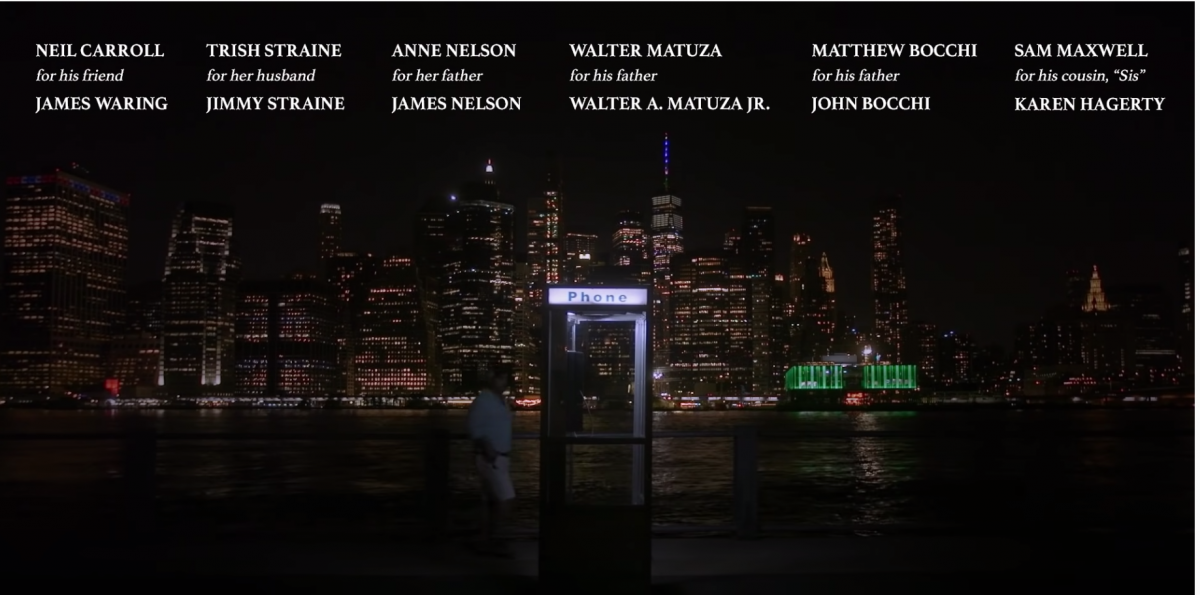

In NPR’s video, “They lost loved ones in 9/11. We invited them to leave a voicemail in their memory,” six people who lost a close friend or family member during 9/11 had the opportunity to leave a voicemail to their loved ones. To collect the interviews, the NPR team set up a phone booth in Brooklyn Bridge Park, from which the new World Trade Center can be seen. The video allows its audience a glimpse into the raw conversations these people have with someone they miss.

Mito Habe-Evans, NPR’s supervising video producer, spoke with Storybench about her work on the project and her role in NPR’s video production.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I was reading a little bit in your bio on NPR and you use the phrase “smart with heart.” I’m really curious to hear more about what that concept means for you and the projects that you work on.

We were trying to figure out how to differentiate ourselves or just conceive of what is the type of work that we want to do, and kind of looking at the work that we were most proud of and trying to find a common theme.

The “smart” part is that there’s always something of value in that it doesn’t necessarily have to be so blatantly educational, but that there’s something that you take away where you feel enriched in some way beyond just entertainment. It’s this idea that you’re somehow enriching the lives of people, and so it feels more like you got some sort of understanding of humanity.

I think the “heart” is that there’s some spark. We don’t just do straight explainers. There’s always some human element. It’s a little bit intangible, but it’s got some element of intimacy or warmth, or whatever it is.

Talking more specifically about the 9/11 voicemails project, I’m curious what inspired you and the rest of your team to come up with this video concept. Where did that idea come from?

We have a pretty small team. We get pretty selective about what we decide to put our efforts into for bigger projects that are short documentaries like this. We want to make sure that we do something that feels of a moment, which I think is pretty normal for news organizations. It feels relevant, but we have some sort of sharp angle.

There’s going to be 100 stories about anything. So why would we put all our effort into something that feels the same? We have to be selective with our appearance because we’re small, and so I think it was important to us to come up with an idea that felt like an interesting angle or just a unique approach.

We covered the Trump inauguration in 2017, but the subtext of what the story is really about is this divide in Americans. It was less about Trump; it was more about Americans having this divide. And same with the 2019 eclipse that traveled across the U.S. It could just be event coverage with the clips, but what it’s really about is this human desire to want to connect despite there being this giant polarization in our country, and to be able to come around, and have some unity around something.

And so I think for us, what does 9/11 actually represent to us in this symbolic way? It felt like grief was an interesting theme to explore. This is one moment of collective national grief. It was a very public, big moment of loss that I think a lot of people felt.

We brainstormed about different things that we found interesting, and I remember going to the 9/11 museum and they have this exhibit where they’ve collected voicemail from some of the folks who had died. So it’s a bunch of people calling in, gradually getting more worried and being like, ‘Can you please call me?’ and it was just so affecting. I remember just being so moved by that.

There’s something so intimate about hearing a voice in your ear, and that’s something that makes radio special. We’ve always tried to kind of capture that.

Within our team, the idea of this wind phone got brought up from Fukushima. So that came up, and we liked the idea for that, so we were like, OK, how do all these pieces fit together? Do we set up a phone booth? I think an early iteration of this for a while was doing a setup at the 9/11 memorial, and setting up a phone booth and inviting people, anybody, passers-by to come in and leave a message for somebody that they’ve lost.

The alternative is to have people come and leave their remembrance for 9/11 more explicitly, but that also felt like: How much are you going to get from people in a real, visceral, honest way? Maybe you can find folks, if they’ve come to that 9/11 memorial, they might be in their feelings about it and be contemplative and maybe have something heartfelt to say, but it still didn’t feel quite right.

I think also the fact that we’re at the 9/11 memorial had to be more obvious by the visual. We want to show that we’re there, and we knew we wanted a reveal in that it doesn’t start with any kind of technical look at the 9/11 memorial. We wanted it to start with ‘hello,’ like some conversation where even if you note from the headline ultimately that this is going be about 9/11, the experience of watching it is that there’s a little bit of intrigue about what the conversation is about, and then you realize that it’s about 9/11.

So there has to also be something about the location that then reads like, “Oh, I see where we are. We got to Ground Zero, and we went through a location scout and we tried to find a site that would work. It’s such a beautiful place. If you’re on site, you can look down and see the holes and the way the memorial is built, but I think from a video standpoint, where you’re trying to also film people at eye level, it’s really hard to get a shot that actually feels like a significant place without explicitly telling people and knocking them over the head. And I think that was a point where we got a little bit stuck.

So at that point, it kind of clicked while my fellow producer and I were on site. We sat down and were like, “Hey, how do we make this work,” and we shifted the frame a bit and flipped what our connection to 9/11 was, which was “Let’s actually talk to people who have lost somebody in 9/11,” and then we don’t have to be at the site itself. It’s still about grief. It’s universal. We always try to find some universal human story within the specifics. Grief is universal, and there is something that feels significant about 20 years of grief and listening to somebody who has experienced that and their connection that is beyond what the story of 9/11 itself is.

In listening to these people’s stories, what stuck with you the most about what they said in these voicemails? What do you carry with you now from these six people?

It was about grief and the fact that that loss is still felt so acutely. Counterintuitively, it’s a little bit comforting. If you lose somebody, there’s this fear that you’re just never going to see them, that you might lose their memory in some way.

[I was] reassured that people’s memory can still live so strongly after 20 years, and the way that the folks who participated talked to their loved ones felt so present and that was comforting.

What were the challenges in connecting with these people, if there were any?

There were two things. One is actually getting in touch with people, and another is making sure it wasn’t exploitative and that we were sensitive to their experiences themselves, and not just trying to mine their experience of grief for the benefit of the audience.

We got in touch with a lot of different organizations. We found Facebook groups. We looked up survivor organizations. And then promptly, I think our most fruitful endeavor was that there was a letter to Biden that was signed by a bunch of survivors.

We started being like, “OK, let’s just find people and call them up.” We went down the list and divided the list up in our crew and called a bunch of disconnected lines that don’t exist, called a bunch of people who were not the right people. And eventually, we got in touch with folks.

I think almost everybody who we talked to really loved the idea. And there were people who loved the idea, but didn’t feel comfortable being on camera and participating. I think we were bolstered by having conversations with actual survivors that [gave us] positive feedback about the idea.

One thing that we learned from looking at the wind phone in Fukushima is that it’s not meant for an audience; it’s actually a cathartic, therapeutic experience for the person making the phone call to feel like they’re talking to somebody. We consulted a grief counselor, and he was saying he liked the idea because he’s observed that one of the hardest parts of grief is the loss of connection to the person — the things that are left unsaid or just not being able to talk to them. And so [he thought] that this would be something that could be really beneficial in a therapeutic way as well.

What we wanted was for people to be able to have an honest, real conversation and for them to get something out of it — not to present anything outwardly or worry about explaining anything to an audience. They can just have the conversation, and they can make whatever references they have that are personal inside jokes or whatever.

We wanted to be also sensitive to the fact that this might bring up a lot of emotions in the moment, and so we also provided them with some resources for counseling after so that there was some care. We wanted to make sure that on site we were all able to be present; and oftentimes on a video shoot, you’re scrambling and you’re trying to juggle talking to the subjects while also setting up cameras and dealing with all the technical stuff and the scheduling.

We just wanted to make extra sure that we weren’t in the position where some things were going technically wrong or we were kind of freaking out but that we were able to show up and be present with the people who are giving us their time and laying their heart out. We made sure that we had folks on our team who were dedicated to greet the subjects and to have time for them and to talk them through the process.

What do you hope that people watching take away from it? What’s one thing that you would hope that the audience leaves this experience with?

I think it’s the same takeaway that I have. The strength is our bonds as people, as humans, our bonds to each other. They can be so strong and they can last, and I was hoping that this would be some source of comfort for folks who might have more recently lost somebody, to know that they wouldn’t forget that person or that that person wouldn’t be forgotten by other people either.

- How NPR used voicemails to explore national grief 20 years after 9/11 - October 23, 2022