How The New York Times transformed its “Diary of a Song” series with FaceTime and social media

Think of your favorite song and imagine calling the artist on FaceTime to ask them how they made it. The New York Times series “Diary of a Song” puts viewers in that unique position, with what feels like a one-on-one lesson on the songwriting and production of the latest pop songs.

The concept for the series stems from an earlier version of artist-interview videos called “Making a Hit.” In April 2018, the Times introduced the “Diary of a Song” series, incorporating Apple FaceTime and a suite of digital storytelling techniques familiar to social media users like TikTok videos and other crowdsourced content.

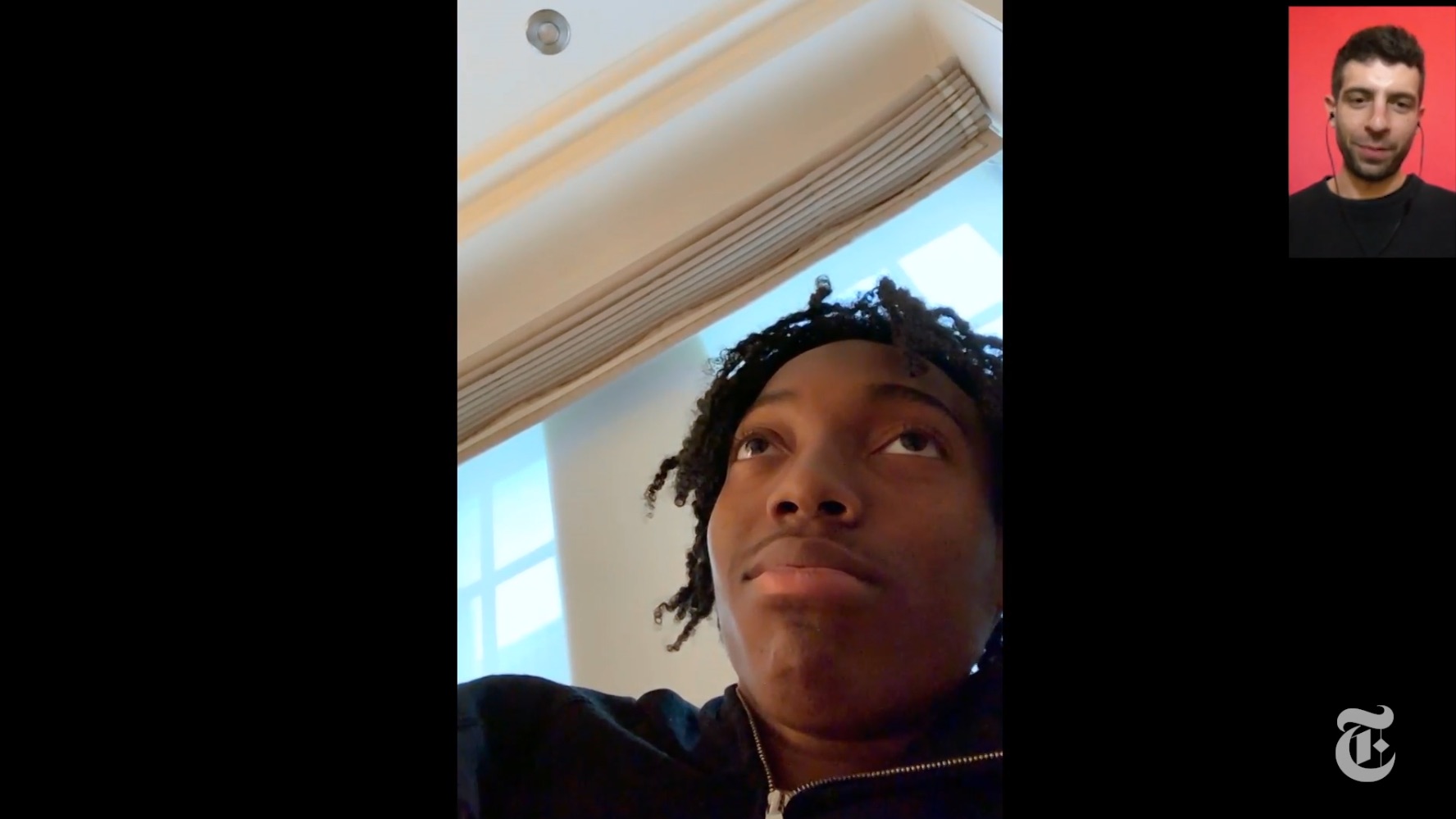

With “Diary of a Song,” the Times has married the intimacy of a video chat with engaging storytelling methods that visualize the song-making process. The most recent installment of the series deconstructs the making of Lil Tecca’s song “Ransom,” which currently sits at number four on the Billboard Hot 100. Past episodes have interviewed Bon Iver, Lil Nas X, Lizzo and Billie Eilish.

Storybench interviewed the “Diary of a Song” team over email to understand how the Times developed the series and how videos with social media appeal can drive audience engagement. The team includes Alice DeSantis, deputy editor, culture; Joe Coscarelli, reporter/producer; Alexandra Eaton, showrunner; Antonio de Luca, senior producer and art director; Mike Schmidt, executive producer; and Zainab Khan, audience editor.

What was the series like prior to the 2018 reformatting? How were the interviews conducted? How were the videos edited?

Alicia DeSantis: When we first did this video with Bieber, Diplo and Skrillex in 2015, the intention was not to make a series. After Jon Pareles interviewed all three contributors in studios with multiple cameras and lighting setups, we edited the piece so the story would, in a way, tell itself (there is no voice over, and Jon is not on camera). We also worked hard to develop a totally new graphic system that we thought added to the analysis of the music. After the success of that piece, we thought there might be an interesting way to expand upon the idea.

The Diary series draws on that experience. We have the expertise of our pop music team driving the selection of songs, the interviews and the storyline. Joe is on camera now, but the idea is the same: to allow the story to emerge in the voice of the people we’re speaking with. You will be introduced to new music, but we also want you to feel as if you’ve been introduced to these artists. That contributed to our decision to do the interviews on FaceTime: the intimacy of the format and the sense that you are meeting these people — in their kitchen, on the road, or wherever they happen to be.

Joe Coscarelli: When The Times made what we referred to as the “Making a Hit” videos in 2015 (Justin Bieber) and 2017 (Ed Sheeran), they were big-budget projects that required in-person interviews with hard-to-book stars, a full video crew and many months of editing and graphics work. (These interviews were all conducted by The Times’s chief pop critic, Jon Pareles, with some input from me behind the scenes.)

The results were slick, informative and forward-looking mini-documentaries, but they proved hard to replicate, leading us to rethink how we could accomplish something similar — pulling back the curtain on the pop machine and songwriting process — with more regularity.

What was the thought process behind transforming the way these videos are made?

Alexandra Eaton: We knew we wanted to keep doing videos about the songwriting process, but we needed to make the production much, much simpler. This meant making big changes to how we filmed the interviews and created the music visualization. The idea came about pretty quickly, in a single meeting, where our art director, Antonio de Luca, suggested we just film the interviews on FaceTime. Everyone knew pretty immediately that was a great idea, and it fit into Joe’s existing world, as he noticed artists increasingly using FaceTime in both their public and private lives.

The second important decision was to create a dogma-style rule: to only use the existing visual languages of the internet, mobile apps and social media. This rule has allowed us to maintain a consistent look for the series, and also creates a shared language between the half a dozen people who work together on each episode. This was also the rare video series that didn’t require a ton of development — we hit the nail on the head in the first new iteration, “The Middle.”

How has incorporating FaceTime changed the way the interviews are conducted or the popularity of the series?

Antonio de Luca: FaceTime has allowed us to subvert the traditional interview process. By preserving the original interface, the interviewer and interviewee feel more relaxed which allows for a better conversation. By removing most of the formalities (the stage, the lights, the travel, the hotel room) artists tend to reveal personal information. Perhaps it feels as though they are speaking to friends and family from the confines of their home. Ultimately the result is more direct. Our audience benefits from this familiar form of video chatting as it simulates the sensation that they themselves are having a direct conversation with the artist.

Alexandra Eaton: Using FaceTime has also allowed us to increase the number of subjects we can interview for each story. We’re much closer to how Joe normally functions, calling up a subject to comment on a tiny story point or to give us a FaceTime tour of a studio. This is a type of freedom we don’t normally have in video, since the costs of a traditional multi-camera shoot limit us to only the most essential subjects and plot points.

Mike Schmidt: One of the big innovations was to include Joe Coscarelli in the piece, which is a critical element. Often video producers will cut the questions and edit the piece together with just the subject interviews. We know that personality-driven videos are a great way to build a fanbase, but more importantly we want people to understand and connect with The New York Times journalists and journalism. Seeing Joe at work is a great window into this world.

Aside from FaceTime, what other digital/social media communication features have you integrated in these videos? Why include these features throughout the videos?

Antonio de Luca: Emojis. Our audience understands these subtle, ubiquitous icons as impactful sub-narrative messages.

Joe Coscarelli: We also try to reference all of the digital media that goes into the song-making process these days. The idea for the series stemmed from me noticing that nearly every artist I interviewed had musical ideas in their phones in the form of voice memos or notes-to-self — little snippets of melody or lyrics, a rough demo or guitar part. We wanted to excavate these primary sources — as well as the tweets, texts, DMs, Dropbox notifications and so on between collaborators — that allow you to trace the creative process from the germ of an idea to a completed song that’s blowing up the radio, Spotify or YouTube.

Between each video release, do you track social media feedback and engagement and use that information for future videos? How is that done for different social media platforms?

Zainab Khan: We look very carefully at our audience comments to see how the episodes resonate. We have a very active Slack channel where we share our favorite viewer comments. YouTube is our priority off-platform, and we use its analytics to learn about the audience we are reaching.

Alexandra Eaton: We also create 15-second teasers for Twitter and Instagram. Joe will often tease the episodes in advance on his accounts, since by this point he has a devoted following that waits for new episodes.

How does the “DOAS” team grow its online audience?

Zainab Khan: The format helps us keep a consistent audience. The artists help us reach new audiences. We find that a specific audience will bring in their following, and because the format is innovative, viewers will stay and watch multiple episodes.

Could you describe the amount of growth that has happened with this series over time?

Mike Schmidt: In the last six months, we made a decision to make more episodes and let them run a little longer. We want fans to be able to spend time with these artists and enjoy all the fun and insightful moments we capture during reporting. Our median viewers have grown and the completion rate has remained steady, which means that we’ve just increased the number of people watching the series and the time they spent on our site watching them. Traffic of course depends on the popularity of the artist and the song, so our focus is on crafting a great story. We hope the audience learns to trust that even if they don’t know the song, they are going to love each new episode.

How does the pop music team decide what song to feature for a video?

Mike Schmidt: Joe Coscarelli is one of the top music reporters in the world and knows which artists and songs are really exciting at any given moment. But that’s not the only element of a great episode – we also want a strong backstory. Lil Nas X is a twitter guru with a flare for marketing and a runaway hit on Tik Tok. Billie Eilish is homeschooled and makes music with her older brother in the family home while mom brings them snacks. Justin Vernon navigates the shift from solo artist to collaborative team builder and grapples with fame. There is always more to the story than just the notes, beats and lyrics.

Of the “DOAS” videos, Lizzo’s episode is the only one with Joe Coscarelli against a gray backdrop or a “professional background,” as Lizzo called it. Every video after returned to the classic red. Does the intimacy of the series with both the viewers and interviewees influence style changes across videos, as far as experimenting with new styles or sticking to what already works?

Mike Schmidt: Sometimes you question yourself on what is really working and want to try something different. Frankly, we second guessed the red background and wanted to try a new gray studio setup for the Lizzo episode. From the minute she asked about the professional background, we laughed and then knew we needed to go back to the red. Now the red Joe feels iconic to the series. We have a very strict visual system but we also challenge it and redefine it with every project. Experimentation is essential to the DNA of the series.

What do you hope viewers learn about songwriting after watching these videos?

Mike Schmidt: I hope that viewers pick up on all the nuance we try to pack into each episode. Making art is not a linear process and requires a ton of work. Sometimes the artists and producers stumble on a great idea right away like Lil Tecca with “Ransom,” but they disagree about which song will be the hit. Sometimes it takes years and years and tons of collaborators and iterations like our Bon Iver “iMi” episode. These are highly skilled folks, the best in the world really, but there is no formula to making great music that resonates. It takes work!

- Behind the scenes at ‘How to Save a Planet,’ a climate solutions podcast - January 29, 2021

- How the podcast ‘Science Vs’ investigated a 1971 virus conspiracy - January 11, 2021

- How The New York Times visualized racist historical redlining and urban heat - September 17, 2020