How the Wall Street Journal conducted a video investigation into the role of the Proud Boys at the Capitol

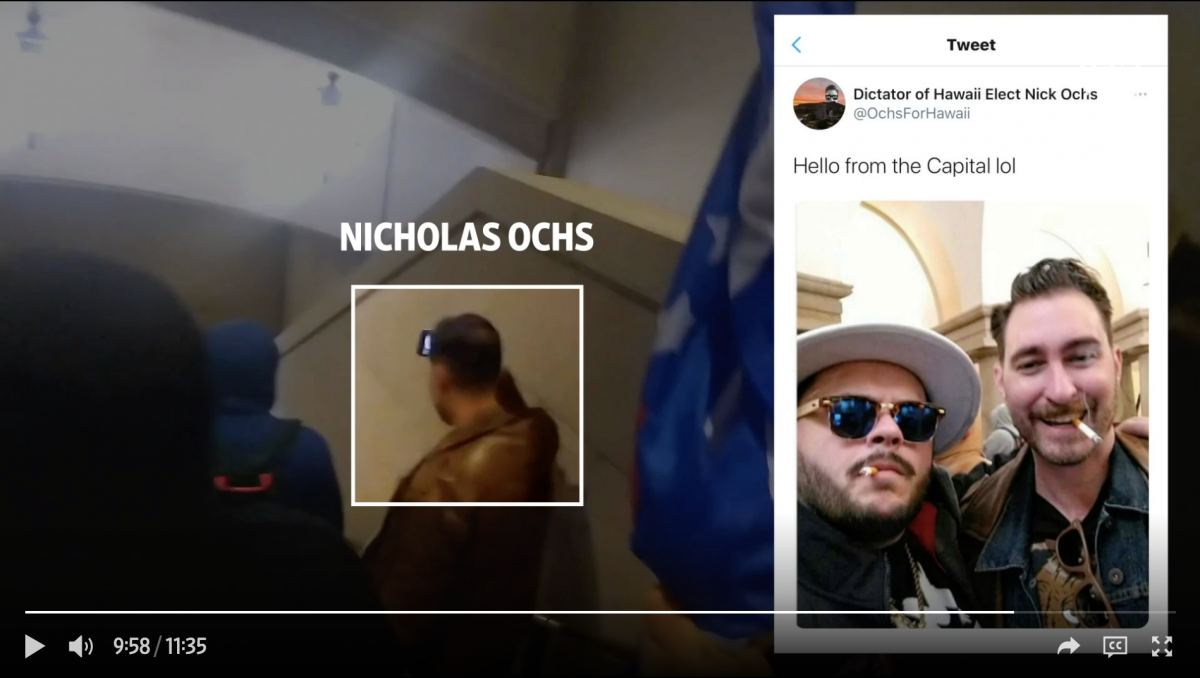

On Jan. 6, 2021, the United States Capitol was breached and stormed by supporters of Donald Trump to protest the results of the 2020 presidential election. Of the many participating groups, the Proud Boys, a white supremacist group, appeared to be particularly prominent, despite their ongoing denial of significant collusion or instigation.

The Wall Street Journal collected and analyzed data in the forms of videos, online posts, interviews, and more, to paint a picture of the Proud Boys’ involvement in the attack. The resulting video investigation highlighted the actions of various Proud Boys throughout the day, demonstrating that they did in fact play a significant role in the event. Storybench was able to speak with three key members of the team who put together the investigation — Deborah Acosta, Frank Matt, and Khadeeja Safdar — to get a better understanding of the video, which provides such a convincing and compelling narrative of the day’s events.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What were your roles? Did you have experience in this type of work?

Deborah Acosta: This was my first video investigation. I used to work at the New York Times, and I do have a lot of experience doing forensic analysis of videos, so I was excited to sink my feet into it at the Journal.

Khadeeja Safdar: We’d never worked together before. It was kind of cool. We were just from totally different parts of the newsroom, and we jumped into a Slack channel. People with totally different skill sets. For example, Frank is super experienced with video, where I’m not at all. That’s what made the project cool.

Frank Matt: We kind of split reporting duties. A lot of people worked on this. I scripted it, others researched. I’d never done what you’d call a video investigation, and it was interesting to see what was new about it. Basically, what makes it a video investigation is that you can plainly see in the video all of the evidence that you’re presenting. I normally do business reporting, so this is not something I typically do.

Video investigations are so unique that you’re best served by having people from a variety of backgrounds working on it. It’s like a puzzle. You want people with different skill sets and different tools. Lots of different types of journalists can bring something to the table. These are complex projects, so if you scale up the ambition, you need a team. Every bit more ambitious these projects get, the more it makes sense to bring more people into it.

Why was this presented as a video investigation? How did the idea for this format develop?

Frank Matt: This was a new kind of project — much more ambitious. We wanted to name individuals and really get at their intent. Our video department has had the ambition for a while to do more projects like this, but the opportunity doesn’t always present itself. This was a prime candidate, simply because of the sheer volume of visual content to unpack.

Khadeeja Safdar: I don’t think it was set in stone that it had to be this way. It was like, “Just come on board — this is the footage and we’re going to dive into figuring out who the key people were.” It was presented as a broad problem, and they let us steer ourselves in terms of tackling it. I kind of liked that. It was like, “This is the problem. We’re going to make a Slack channel. Let’s just talk about it, and we’re going to figure it out.” Frank put a script together, and it just flowed.

How did the team function? How did this final product come together?

Khadeeja Safdar: We were working through a Slack channel. It was all kind of a blur. It was really interesting — they put a whole bunch of people together and we were studying the footage. Deb would go through, see something interesting, take a screenshot, put it in the Slack channel. That’s how we ID’d a lot of the Proud Boys. We hadn’t done anything like this before. We just had to dive in and find out who these prominent members were. It was a lot of research — a lot of digging through the internet.

Frank Matt: The name of the Slack channel was “Orange Hats,” because there were these guys in the videos with orange hats, and we kind of started from there. And then we thought, “OK, what’s the role of the Proud Boys?” They were making a conscious effort to downplay their role, and we wanted to assess that. A lot of the process was watching a ton of videos. Some videos were hours long. Luckily, diligent researchers archived stuff before it was deleted.

Deborah Acosta: I did a general count and I watched more than 700 videos. We watched livestreams, and were able to identify people through that. We were trying to figure out the movement of people — where were they coming from? Who were they connecting with? What happened moment to moment, hour to hour? That helped us reconstruct the events in a way that was linear. Basically, the whole edit was a timeline. It started early in the day and ended later on in the day. This was also fun and different because it was remote. We can find all this data, but how is the editor going to know what any of this stuff is and where it goes? So we had to go moment by moment, screenshot by screenshot, and label what elements we had, who were the key players, and so on. Even though we were all in different locations, we were able to work so cohesively. I was surprised by how seamlessly we made this work — just blown away by how quickly we put it together.

How did you manage to actually obtain all the footage and other data?

Deborah Acosta: Parler was really helpful. All these guys use Parler kind of like Twitter. Twitter was also really helpful, but it was taken down before we even started our investigation. There’s a whole army of people out in the world who are like homegrown, open-source investigators, and they’re putting little clues out. It’s not always great, but it was definitely a great tool for finding a lot about what happened on that day.

“There’s a whole army of people out in the world who are like homegrown, open-source investigators, and they’re putting little clues out.”

Deborah Acosta

Khadeeja Safdar: It was a source grab. We looked at documents, interviewed people. The Proud Boys have been kicked off platforms so much, so we were also following these folks on various alternative channels. It’s not mainstream stuff anymore because a lot of the mainstream platforms have kicked them off. On Telegram they post podcasts and videos — it was like we were entering their world.

Frank Matt: Some we found in random places and then tracked down the sources of. There were also a bunch of people who made efforts to compile archives. For instance, a researcher had tried to download as much video from Parler as she could before it got deleted, so there were these massive archives from Parler available to browse through. Just tons of them. A lot of independent researchers made public these archives of livestreams and downloaded them before they could be deleted. There was tons of video available if you went looking for it. It was just a matter of digging in and spotting the interesting stuff.

Storyful was also crucial. They verify and acquire licenses for video and so they helped a lot with the footage.

What were some of the major challenges of this project?

Frank Matt: So much material was being deleted. It was a race against the clock to make sure stuff was preserved. And then we just had to be so careful. Do we know what we’re doing, or do we just think we know? Is that the same guy, or just someone who looks similar?

Khadeeja Safdar: We identified more people than the video showed, but the standards are so high at the Journal. In order to publish information, we have to be absolutely sure it’s true. The guy “unidentified Proud Boy” — we knew who he was, but it was hard to get a direct family member on the phone to confirm. We had to be certain that an individual was who we said they were… like you have to be absolutely sure when you’re calling someone a Proud Boy and saying they were part of a riot. We can get a lot of clues of who people are from other sources, but we often have to clear a higher bar than those sources. Our standards are so high to make sure everything is correct. We have to think — how do we know this? Did we verify it? Every process is like this at the Wall Street Journal to make sure everything we’re saying is a fact.