How this former public school teacher helped uncover education inequities for The Boston Globe

Mandy McLaren, a reporter for The Boston Globe, witnessed how low-quality education can impact students during her former career as a public school teacher in New Orleans. Taking it to heart, McLaren is now a member of The Great Divide, a team at the Globe that investigates imbalances within education systems.

Storybench sat down with McLaren to discuss one of the team’s multimedia projects, “Lost in a World of Words,” that analyzes the literacy crisis in Massachusetts, as well as how her former career influences her writing.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What got you into journalism?

McLaren: In my hometown, we had a little daily newspaper. I lived in a house where my mom always had the news on, like we always watched Channel 5. However, I didn’t get interested in the news until I was a freshman in high school when 9/11 happened. I became attached to the TV and it gave me comfort to know what was going on. From there, I got it in my head that I would become a war correspondent in the Middle East.

Life works out in weird ways. I took a hard left in my plans and taught in high-poverty schools in New Orleans for seven years. I got to see firsthand all of the systemic issues that burden low-income schools.

One time at [the] beginning of the school year, I was trying to set up my classroom culture and motivate the kids about what they are learning. I said something corny to the students about wanting them to be able to do whatever they want with their lives. One of my kids said to me, “Miss McLaren, is this what you wanted to do?” And that got me thinking. Long story short, I ended up going to American University in [Washington] D.C. to get a master’s in journalism. I decided to marry the journalism and education.

What stuck out about this story in particular?

It definitely stems from my experience working in the classroom. I was a [special education] teacher and I had many students who struggled with reading and writing. I was a teacher who really was unprepared and knew little about the brain science behind how kids learn to read. I have some students that come to mind when I do reporting like this because I think about how they struggled and how much I wanted to help them, but in the end I couldn’t do that much. I still wonder about the trajectories of their lives.

Why was it important to you to include many forms of media?

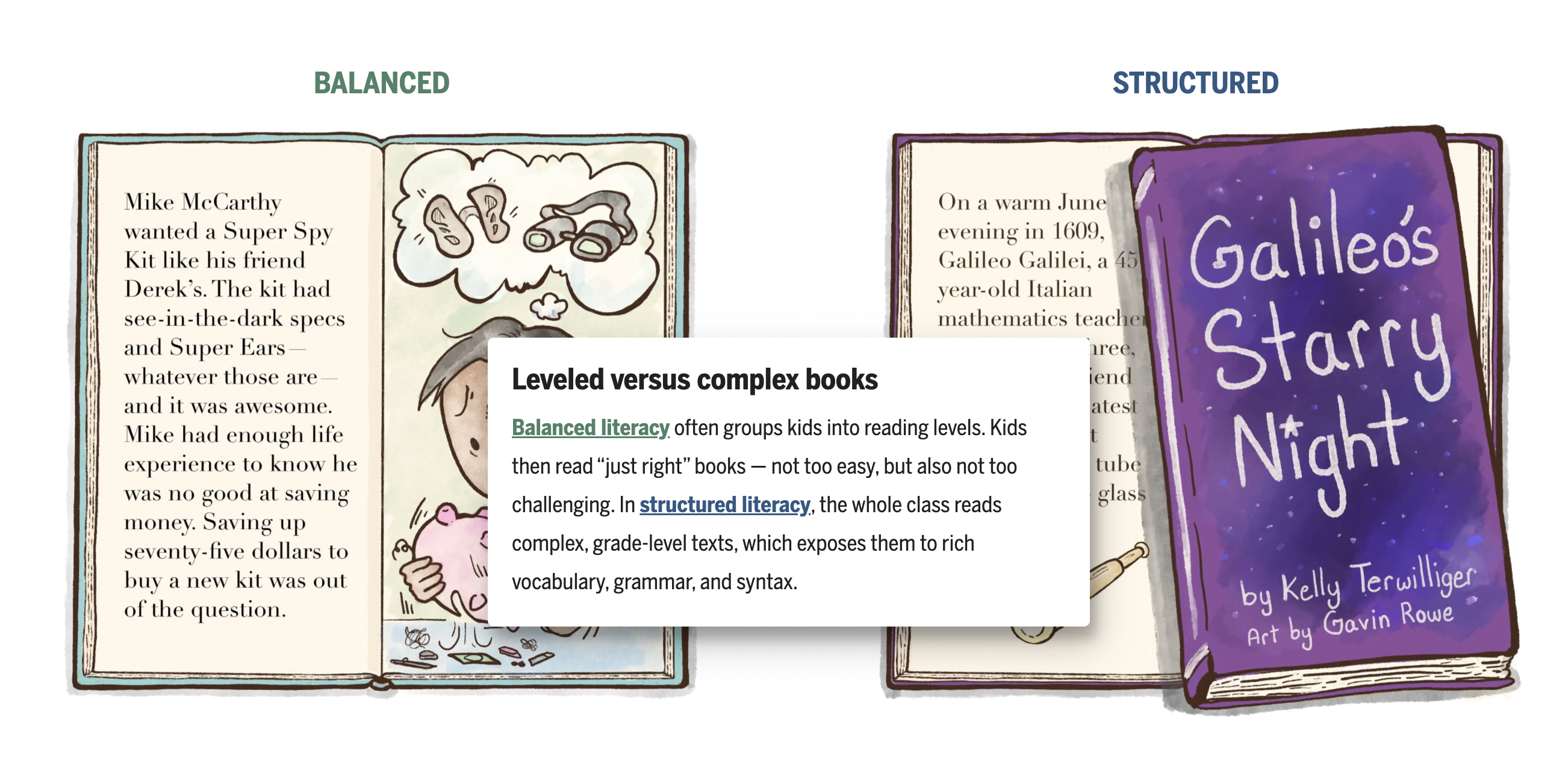

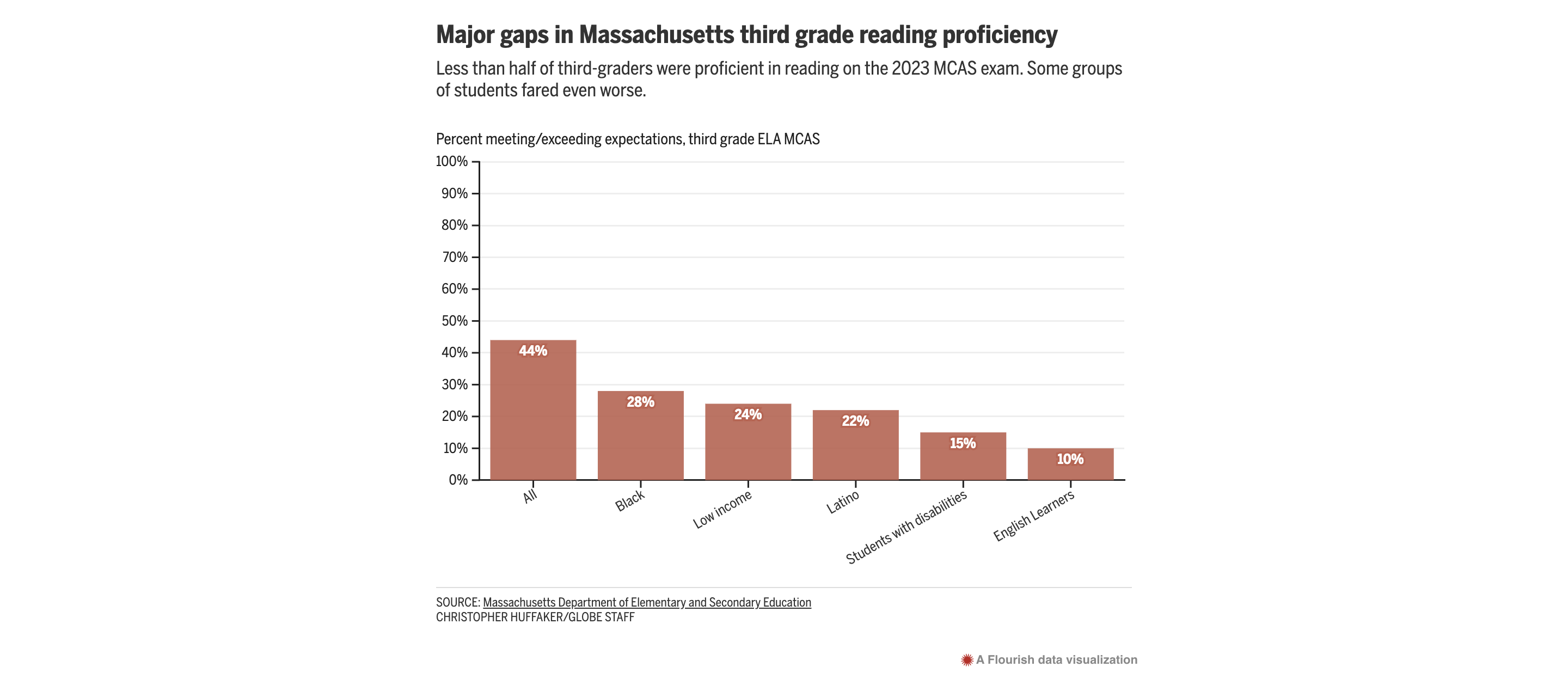

All the different components serve a different purpose. You don’t want one element to repeat and do the same thing that another element does. The video was able to take us more into the classroom in a specific school district than you’re able to in the print story. The infographics help the reader pause and think about the numbers behind the story. The photos establish a connection between the reader and who they’re reading about. And then the last element we call the “scrolly” because you scroll to activate it, that was deliberate on our part in thinking about, “How can we make the story digestible to a reader without boring them?” We are lucky to have a talented web developer in-house who did their magic and made it look really amazing.

What is your personal process for conceptualizing a story?

It’s never the same. Sometimes, it’s that you keep hearing similar things from parents or other sources on whatever beat you’re covering. When you keep hearing something over and over again, your instinct is typically to look into that. Other times, you were analyzing data and something stood out to you or maybe you go to a very boring public meeting but there’s a slice of juicy stuff in there. For me and literacy, I was partially motivated by previous reporting on the topic. For example, I listen to a lot of audio documentaries by Emily Hanford, who is a journalist that has done a lot of work on literacy. At some point, a situation came up in Kentucky where there was a new law that was [going to] allow superintendents to choose curriculum. It was very boring and nobody was writing about it. But I sort of made the connection like, “Oh, if superintendents now get to choose curriculum, that could have really big implications for how kids are being taught to read,” and sort of just snowballed from there.

What is your favorite part of being a journalist, especially in this beat?

It has been hard in a lot of ways. As a teacher you get immediate feedback on whether or not you’re doing a good job based on the kids’ reactions. With reporting, I can work really hard on something and put it out into the world with no immediate reaction. That is a challenge that I’ve gotten more used to over time. With this project, I’ve gotten emails from parents or educators saying, ”Thank you for writing this.” It really validates my experiences. So, it just sometimes comes in a different format.