A look inside the Boston Globe’s immersive Cape Cod project

In late September, the Boston Globe published an in-depth report on how climate change is affecting Cape Cod. Nestor Ramos, the writer, said the intent of the article was to show readers how climate change is drastically changing this popular vacation destination. He spent months on the Cape, speaking to residents and workers and learning about global warming’s effect on the Cape’s economy and geographical landscape.

Storybench spoke with Ramos about reporting the story, his work with other Globe reporters to make the article a visual, digital package, and the response from readers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to take a closer look at global warming on Cape Cod?

Nestor Ramos: The story dates back to really when Liam’s, the clam shack that’s in the first chapter of the story, was hit by that storm in March 2018. Some editors here, Brian McGrory, Anica Butler, some others, got to talking after that about what all is really going on on the Cape as it relates to climate change and thought about how we might pursue a story that really focused in tightly on the Cape, and sort of answer that question for the folks that only go down there once a year for a week.

It sort of gained some momentum over the months and an editor here, Steve Wilmsen, who’s really interested in our climate change coverage but also anchors our narrative writing, really had a vision for how it might come together in terms of our online presentation. He was working before I was brought in with photographers and digital designers and data journalists to sort of lay the groundwork. And finally Brian McGrory, the editor of the Globe, brought it to me and asked if I might be interested, and I was.

So the team approached the project with all these digital elements in mind, the maps, the data, the videos, from the beginning?

If you’re gonna tell a story where the Cape is so foundational, you need it to be visual. You want it to be close to home and to feel urgent in a way that words can only do so much. So we, from the outset, had been planning to marshal all these different forces for photo and video and different kinds of storytelling to really let people see and hear and experience the things that I was writing about.

What was your reaction when reporting this piece?

What stood out to me and I still think about a lot is the extent to which these changes are imperceptible, unless you know exactly where and how to look for them. But if you’re out there every day, or if you’re out there three times a week, every week for 15 years like Dave Spang, who’s at the beginning of the story, you realize that the place where you stood 15 years ago is gone. And it’s out over the water now because you physically have to pick up your little shed and hoist it backwards a few yards every year, or risk it falling in. That idea that things look the same but aren’t, as a result of climate change, is really compelling to me. And the idea was to sort of force that notion on people so that they looked at the physical environment when they’re down there on vacation a different way.

You also see a lot of the physical environment just scrolling through the story looking at the pictures and the videos.

Yeah, and it was really tough. I know for John Tlumacki, who was the photographer on the project, it’s really tough to photograph climate change. For a long time, the pictures we take of climate change are starving polar bears and things that feel kind of remote. But how do you shoot climate change in this place that, fundamentally, is fun and beautiful and a sun-splashed vacation paradise? Tlumacki was able, through months and months of work, to find pictures that tell that story. And he and the photo editors spent a ton of time going through paragraph by paragraph and figuring out where to put photos throughout the story online, so that they had maximum impact; how to do those horizontal galleries as you’re scrolling vertically through the text in places where you’d want to stop and see this person that I’m talking to or this phenomenon that I’m describing.

The videos do the same thing; as you scroll down, and I’m telling you the story of John Ohman and Liam’s clam shack, all of a sudden there’s John driving to the beach where it used to be, and you’re right in the car with him. And this is what he sounds like, and this is his son, and here they are trekking for the first time around the place where they spent his son’s entire life that is now just a dune. I can write that but not as viscerally as it is once you’ve seen it.

One of the original ideas of the story that didn’t end up being workable, at least for me, was that the story would be sort of centered around a trek that I would make mostly on foot. And it would be a literal sort of travel log where I’m going from place to place and you’re following me on the route. It didn’t work logistically for a lot of reasons and storytelling-wise for some other reasons. Once you’re doing a straight line geographically, the subject matter isn’t necessarily where you want it narratively. So we went away from that but we kept the sort of notion that the whole story is, at some level, a trip to the Cape. You come down over the bridge, the way most of us do, and you go to the beach, and you eat some oysters or lobster rolls, and you go bird watching in the marsh, and eventually you come around to the end of your week there. And the idea was to structure it that way.

How closely did you work with John Tlumacki, the photographer?

We worked together quite a lot sort of philosophically, like we talked a lot about what the story was going to say. I sent him drafts all the time as I was working it and reworking it, but we traveled together very infrequently. Even though each of us knew what the other was doing, he, because he is a great photographer, was charting his own course a lot of the time and finding things that I hadn’t found, frankly. There were very few occasions where I was, like: I need John to come with me to this thing so we can take a picture of some specific guy or thing. We didn’t do a lot of that. He just knew what I was working on and would spend all night sitting in a marsh waiting for those nocturnal crabs to come out or would get out on a fishing boat (because) he knew there was gonna be a passage on fisheries and did some of his own reporting.

Is that similar to the relationship you had with the video editors when they made that documentary short and the videos seen throughout the piece?

There’s a documentary short, and then there’s three integrated videos in the story that sort of formed the spine of that documentary. And I would say in the first one with John Olman, we worked together quite closely, because John was the source of the story. And I had made the first contact with him, and we did some of the interviewing at the same time. So the next one on the whimbrels, they took it much further in a way that was great, I think, and followed Brad and his whimbrels to the point where Caitlin, our videographer, was sitting in a kayak. I was back frantically trying to rewrite the story and Caitlin was sitting in a kayak on Loagy Bay when Ahanu alighted and Brad the scientist grabbed the back of her kayak and shoved it toward Ahanu so she could get the shot. So, that was an example where they took what I had found and added so much to the storytelling that’s not in the print version.

The story works without it, but if you want to learn more and really experience what it was like to follow this whimbrel around the world, you can watch this video for two minutes. And the third one, about oyster fisheries and tracking the oyster from a seedling to your plate, was something they pursued almost entirely on their own. They had a daylong shoot at an oyster hatchery but they took it much further in a way that added a ton to the story.

How do you think you would have approached reporting the story differently if it was only for print and had none of the visual elements?

As a reporting exercise, I started by really trying to understand the science and spend a ton of time interviewing scientist after scientist. Many were super helpful and are giants in the field that didn’t end up in the story because quotes from scientists often cover climate change to little effect. But I think I would have spent more time on the visual elements of narrative writing and really try to describe things better, particularly something like Dave Spang standing on the cliff.

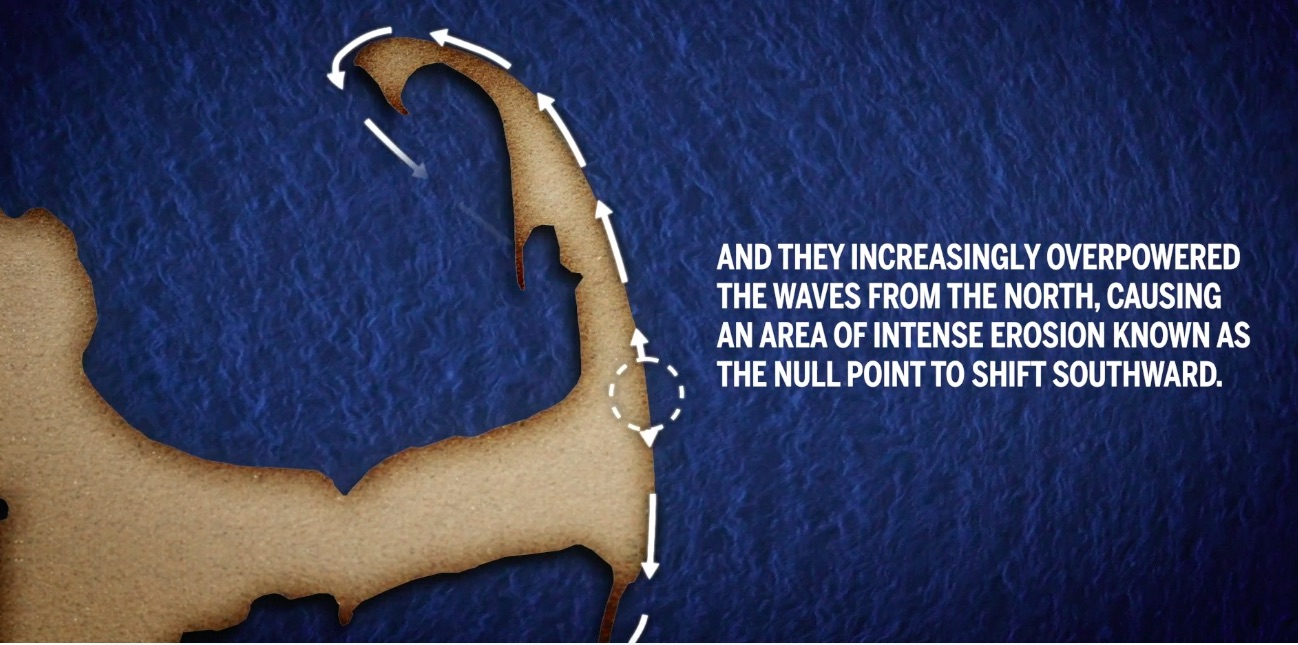

Without sort of the crutch of images to help people understand and put a face to a voice, you have to write it differently. And that certainly changes how you report. I probably would have ended up having to go back to people again and again, more even than I did to clarify details and make sure I had everything right. It changes what you write down in your notebook if you feel like there’s no way that people are going to be able to see what you’re talking about. Some of the science stuff, like that animated map we have of the Georges Bank theory, I think explains that phenomenon better than anything I could do in strictly black-and-white words.

What was the reaction like from readers after the story was published?

It was really overwhelming, to be honest. I was a little bit nervous about how readers particularly on the Cape would respond, because this is their lives. A lot of this stuff is familiar to them and really challenging, but that too was overwhelmingly positive. It was a rough summer for the Cape, between the sharks and the tornados. I think they were feeling pretty beaten down. And tourism is what most people down there make their livelihood on, directly or indirectly. So that doubly hurts, but I was really, really gratified to hear people saying that they felt like this is how they would want to tell their story. I tried very, very hard to quote and picture really only people who live and/or work on the Cape –you don’t see a lot of outside scientists rambling on in there or government officials, things like that. This is the story about the Cape told largely through the voices of people who live out there, and I think they responded to that.

And then around the region and the country it was quite popular. It was among the highest subscription drivers for the year on our site. It had a huge engagement time online. Typically that average is like a minute per story, which includes all of the folks who just back out of a story as soon as they click on it or only read the headline. But this was like well over 6, 7, 8, 9 minutes for most of that first few days, which suggested people were legitimately reading it. The videos had great play rates, like people would stay on them for a long time actually watching them. So that was really encouraging. And then Bill McKibben, a really well known environmentalist, tweeted it. Elizabeth Warren tweeted it. Folks like that who are sort of at the forefront of this movement really thought it captured the reality. And being accurate to the science, and finding the stories that reflect the science, rather than the other way around, was really important to me. So I was very gratified.

- A look inside the Boston Globe’s immersive Cape Cod project - April 13, 2020