From Ancient Egypt to Charlie Hebdo: How technology has enabled the spread of political and religious satire

In 2011, Charlie Hebdo was firebombed after an edition “guest edited” by the Prophet Mohammed featured a caricature of him promising “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter!” Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnie, the magazine’s editor at the time (among the 12 people slain in last week’s terror attack on the satirical magazine’s offices), not only refused to apologize, but said in an interview with Le Monde, “We have to keep at it until Islam is as banalized as Catholicism.”

The “banalization” of Catholicism is the outcome of both rising secularism and a centuries-old tradition of religiously themed satire, which is particularly strong in France. Its effects were accelerated by the evolution of distribution technology, from simple drawings to woodcuts to newspapers to the Internet.

Here’s a look “back” at that evolution.

Ancient Egypt

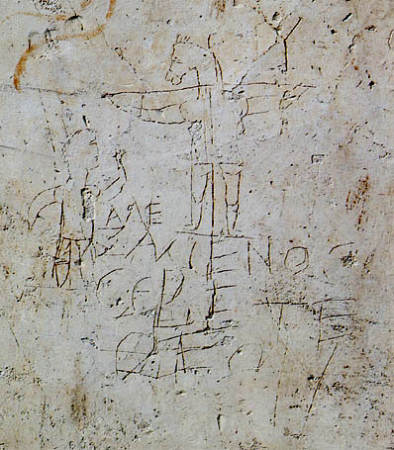

It’s impossible to say who created the first religiously themed satirical illustration, but one candidate for the first known political cartoon is a nasty caricature of King Tutankhamun’s father Akhenaten, drawn in 1360 B.C.E. Sometime in the third century C.E., an unknown Roman artist scratched a crude image of Alexamenos, a Christian soldier, worshiping his god—depicted as a crucified man with the head of a donkey—into a wall on the Palatine Hill. Alexamenos likely didn’t find his portrait as amusing as the artist did, but the audience for it, like the audience for the Akhenaten image noted above, would have been pretty limited—just those people who happen to walk by the wall where it was carved.

Martin Luther

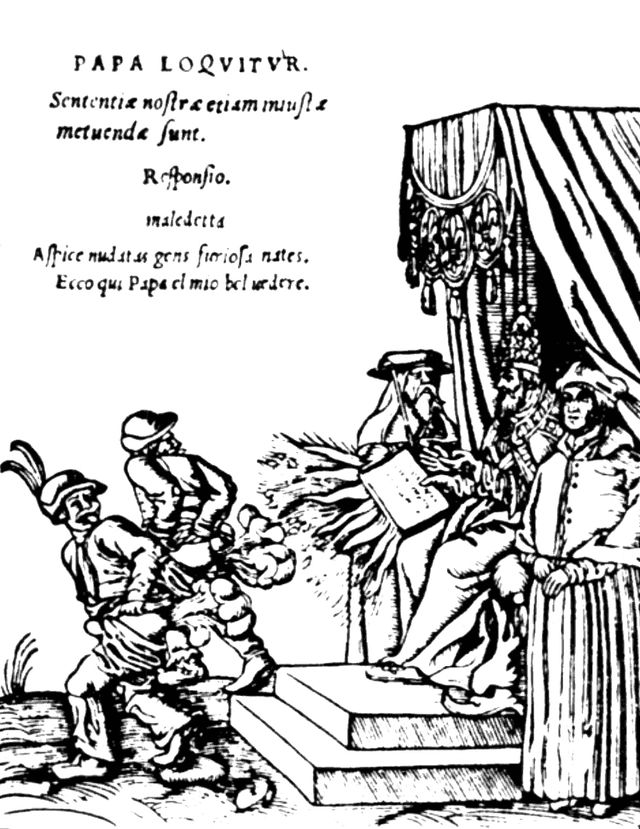

By the 16th century, the development of woodcuts, copperplate engravings, and the printing press made widespread distribution of satirical cartoons both possible and economical. Martin Luther and other German religious reformers took advantage of the new technology to distribute broadsheets illustrated with pointed criticisms of the Catholic Church. The broadsheets could be printed in quantity, and the illustrations allowed them to reach a largely illiterate audience.

Satire in the 1700s

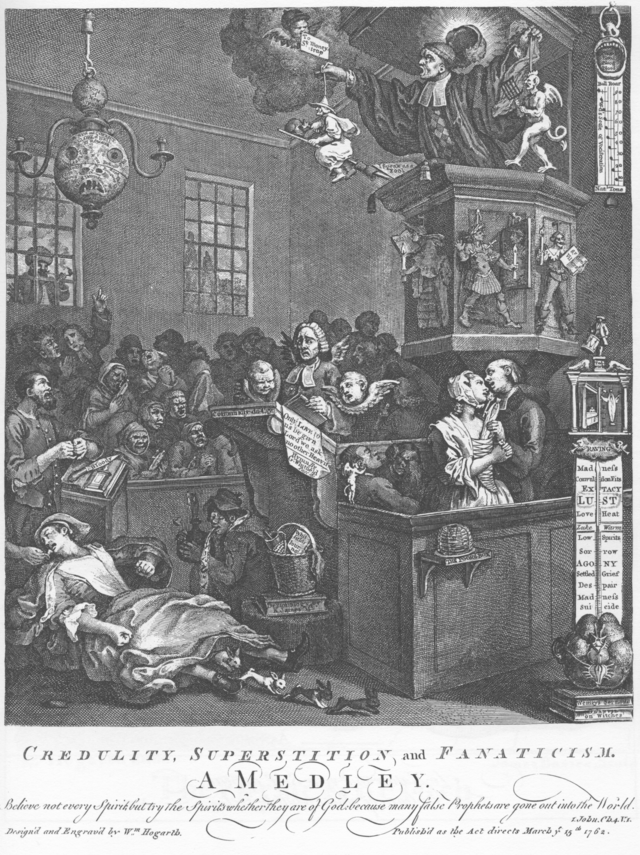

These early examples lighted the way, but the modern history of the satirical cartoon in Western Europe most likely begins in the early 1700s with the English artist and satirist William Hogarth, whom the French called “le premier roi, le véritable père de la caricature.” (“The first king, the true father of the caricature.”) Among his satires of social climbers, the upper and middle classes, and the poor, Hogarth was also known for religious satire.

In Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, Hogarth ridicules Methodism with a potpourri of Catholic imagery, contemporary ghost stories, allegations of witchcraft and demonic possession, and a congregation overwhelmed by fervent emotion and religious mania. A Turk stands outside the window, “laughing at their absurdities, and thanking Mahomet that he has been early initiated into the Koran.”

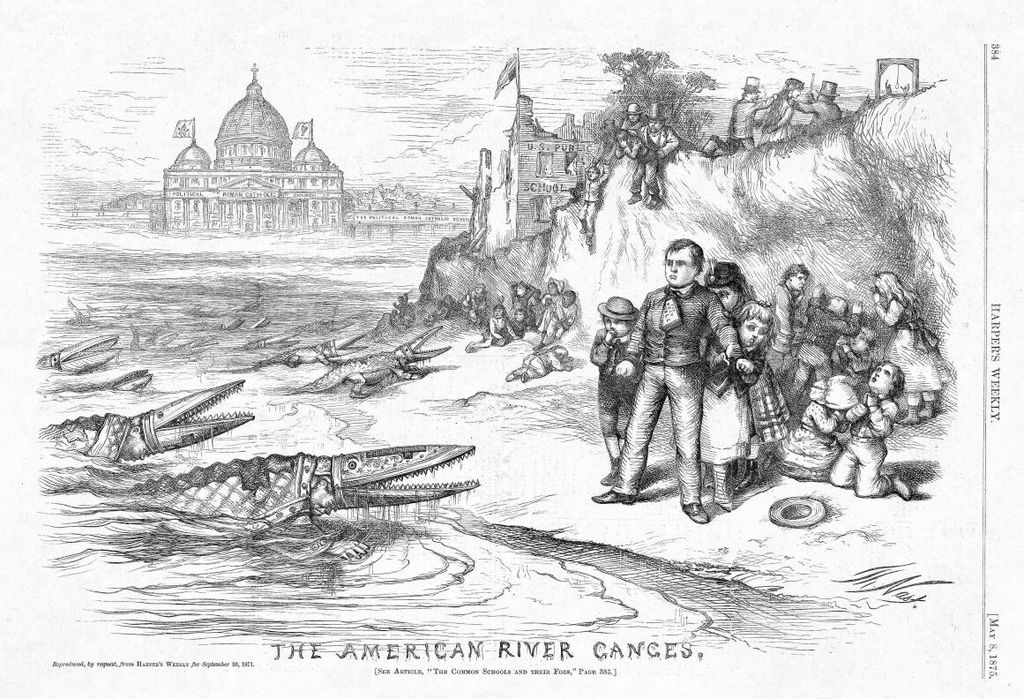

The syndication of cartoons

The rise of the 19th-century newspaper industry was another milestone in the development of the satirical cartoon. Most of these cartoons were political, not religious, though Thomas Nast’s vicious caricatures of Catholics and the anti-Semitic cartoons that were a staple of the 19th and 20th centuries are notable exceptions. As William Hewson put it in The Cartoon Connection: The Art of Pictorial Humor, “the Victorian middle classes… would have suffered apoplexy over a joke against their Christian religion.” Additionally, because newspapers were subject to both governmental and commercial censorship, the cartoons they published were necessarily tamer than those distributed by hand in broadsheets. What they lost in bitter, biting humor, however, they gained in distribution.

As Ryan Cordell’s research has shown, 19th-century newspaper stories were often cut, pasted, and reprinted by dozens, if not hundreds, of publications. In effect, some stories “went viral” in a way that’s very familiar to modern audiences used to reading their news online. The development of syndication further encouraged the distribution of newspaper content to audiences around the world.

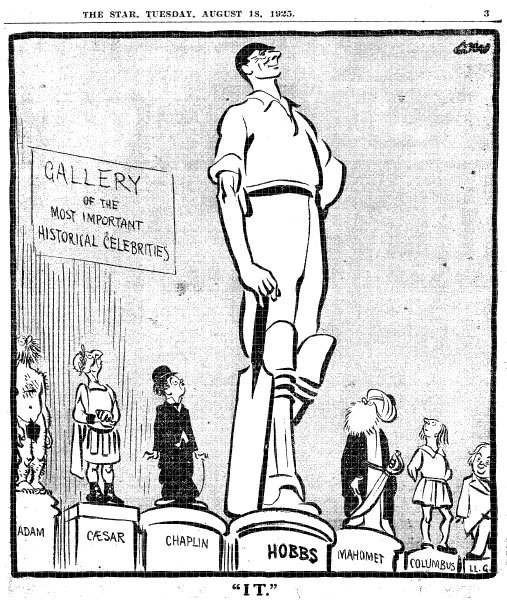

The potential consequences of such widespread distribution became obvious in 1925 when cartoonist David Low depicted English cricketer Jack Hobbs towering above a “Gallery of the Most Important Historical Celebrities,” including Adam, Charlie Chaplin, Christopher Columbus, and Mohammed. Had Low’s image stayed within the pages of The Star, which originally published it, it would likely have attracted little comment. However, it was syndicated to the Morning Post in India, where it “convulsed many Muslims in speechless rage. Meetings were held and resolutions of protest were passed.”

The Danish cartoons

While there was likely no relationship between the “resolutions of protest” and the 1925 riots in India, the same cannot be said for the confrontations over the so-called “Danish cartoons.” On September 30, 2005, Jyllands-Posten published 12 cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammed, presenting them as a response to the perceived self-censorship of artists afraid of offending religious communities, particularly Moslems, many of whom object to visual representations of the prophet. As expected, the cartoons attracted controversy, and the controversy attracted interest. Soon, they had been reprinted by outlets worldwide, including Charlie Hebdo, and some of the protests turned violent.

Nearly a decade later, the shadow of the Danish cartoons still lingers. They have been linked with several terrorist plots against European targets, and figure prominently in discussions about last week’s attacks in Paris.

Cartoons in the age of globalization

While Charlie Hebdo editor Charb defended his magazine’s depictions of the prophet as an exercise in free speech, and Flemming Rose, the editor of Jyallands-Posten, has insisted that his newspaper would not have published the cartoons if it did not consider Danish Moslems full members of Danish society, many other observers have criticized them as symptomatic of the discrimination that Moslems face worldwide. One of the gunmen’s associates, Amedy Coulibaly, who was fatally shot by the police after taking more than a dozen hostages at a kosher grocery store, left behind a video in which he said, “What we are in the process of doing is completely legitimate considering what they do… It has been completely deserved for a long time.”

Before the brutal attacks, Charlie Hebdo‘s printed magazine had a circulation of 30,000 per week. This week’s print run will be around five million copies. Its website, of course, has a potentially global reach. As the Internet continues to penetrate the globe, satirical political and religious cartoons will only spread farther.

Never before have we had the power to reach this many people. That power, of course, is a double-edged sword. Technology may be bringing ideas to the masses, but whose ideas? And when the audience includes the “bad guys,” intent on using violence to express their opposition to certain ideas, we see the dangerous side of “reach.”

Chia Evers is a writer and researcher living in Cambridge, Mass.