How newspaper stories went viral in the 19th century

Ryan Cordell wants to know how news went viral in 19th century America. Cordell, a professor in the English department at Northeastern University, performs this pop culture archaeology by investigating the culture of reprinting, a practice which was rampant in 19th century newspapers. Back then it was not only news, but poems, articles, serialized fiction, and anecdotes that were reprinted–or to call a spade a spade, pirated–by publications across the United States. But how does one explore a social network in which no one has been very, well, social, for more than 100 years?

Through the magic of digital humanities, which is what happens when someone mashes up literary studies with big data. Cordell teamed up with David Smith of Northeastern’s College of Computer and Information Science to find, quantify and visualize which texts went viral between 1836 and 1860, a time before wire services like the Associated Press had caught on. Newspaper editors would find stories in other papers and literally cut and paste them into their own publications.

The pair dove into the U.S. Library of Congress archives to start their quest. They then began to to piece together thousands of texts to see where they were originally published and how far they spread.

Ryan Cordell speaks to Buzzfeed about virality in the 19th century.

What was reprinted?

Poetry

Recipes

Obituaries

Jokes

“Tweet-sized news”

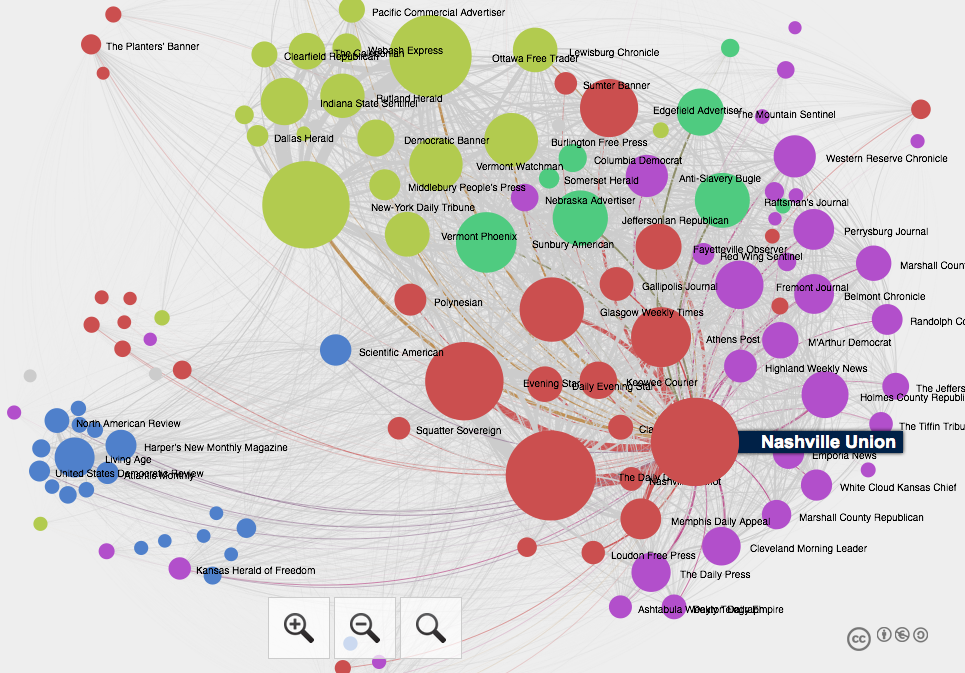

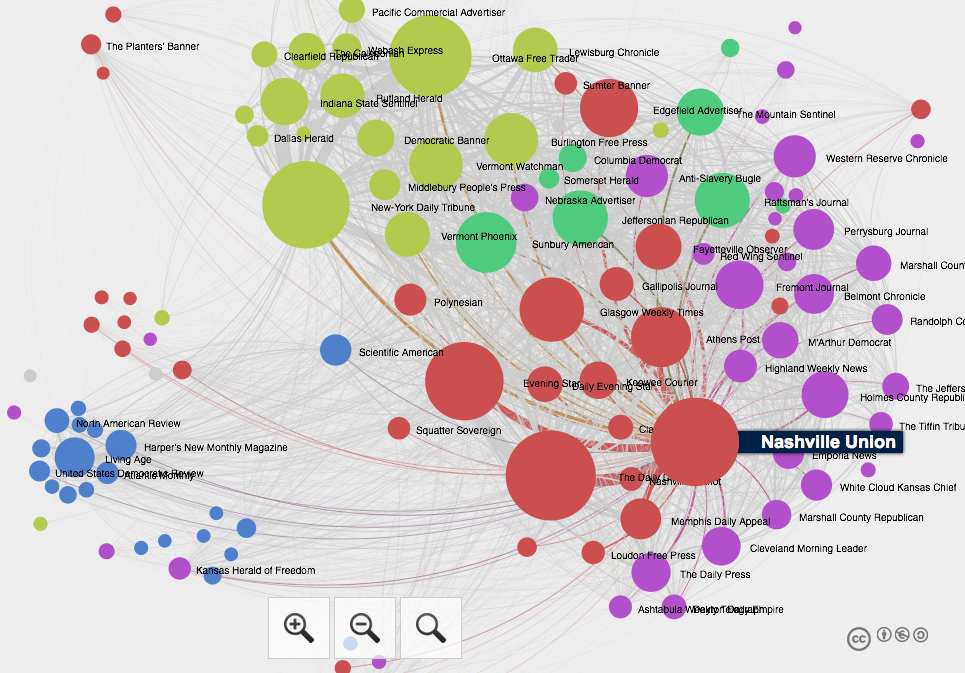

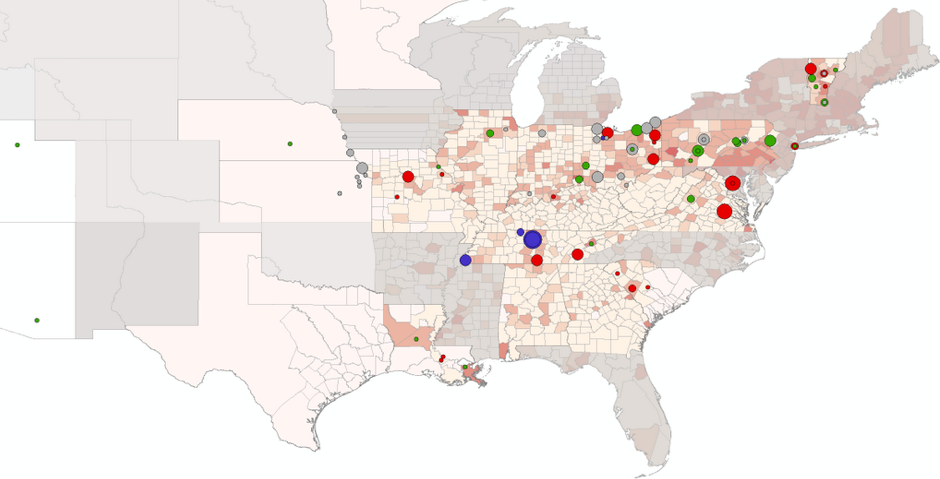

Mapping the spread

Looking through more than 40,000 issues of 132 different historic newspapers in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America archive, Cordell found thousands of texts that were printed over and over again across the country. The practice of reprinting was common. News, poems, recipes, and serialized fiction would be reshuffled into varying lengths and reprinted across the nation, from the New York Daily Tribune to Missouri’s Glasgow Weekly Times.

Cordell knew he had a compelling collection with which to study the influence of newspapers and virality of their texts, but he needed programmatic tools to do several things:

- Automate the search for chunks of matching texts, many of which were jumbled by optical character recognition, the computational method used to scan texts

- Parse and order the texts into a database

- Visualize the texts and sources through network analysis and geographically

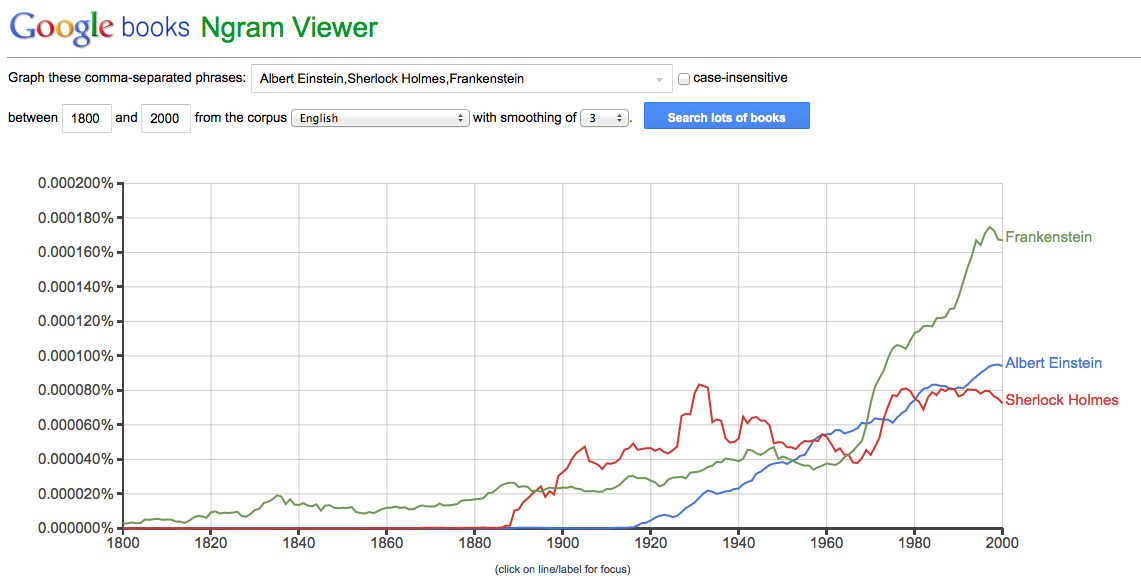

Clustering n-grams

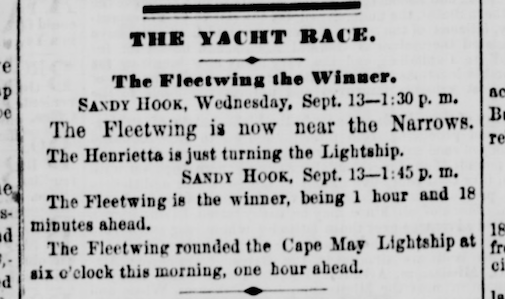

Smith, the computer scientist, did the network analysis. He took the body of texts and clustered them by similarity (which was measured with n-grams: contiguous sequences of characters or words, i.e. The Fleetwing the Winner is a 4-gram). Google offers a free n-gram viewer that charts word sequences from Google’s corpus of books across the years.

Measuring Victorian clout

Using this network analysis, the team was able to suss out which newspapers were the most influential between 1836 and 1860. One might predict that New York, Richmond, and Boston would be home to the major influential newspapers.

But an early and surprising conclusion from Cordell and Smith is that newspapers outside of these major cities enjoyed substantial clout, newspapers like the Nashville Union and the Ottawa Free Trader. Another early conclusion is that Scientific American, one of the only publications they reviewed that is still in business, reprinted much more newspaper content than other magazines of its time.

But the picture might remain incomplete. It turns out the vast majority of historical newspapers have been destroyed. Still, Cordell is sitting on a vast database of antique newspaper clippings and is seeking out collaborators to continue mapping and analyzing it, hoping that clues to 19th century virality might inform our own 21st century understanding of why and what people share.