How Stamen turned a photo archive into an interactive art experience

In 1966, Ed Ruscha mounted a camera to the back of his pickup truck and drove slowly down Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. He photographed every building on each side of the street and assembled the photos into the book Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Ruscha continued to photograph all 23 miles of the famous street for the next 50 years, but the images lay in an archive, unpublished.

While this book “hurdled like a meteor onto the arts landscape,” said Eric Rodenbeck, founder and creative director of Stamen, not many people knew about the following photos. The Getty acquired the archive a few years ago and began the task of scanning and geotagging them all. Then, they brought Rodenbeck’s company in to display the archive online in an interactive and engaging way.

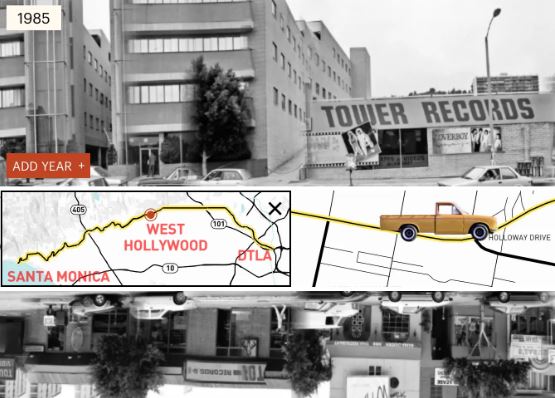

“12 Sunsets” is the product. It allows the viewer to “drive” through images. Storybench connected with Rodenbeck to talk about “12 Sunsets,” translating physical art online, and the future of digital works in museums.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Can you give a little bit of background on 12 Sunsets?

It’s a viewer that lets you compare any of those years that Ed took the photographs with all the other years. You can do things like find the western-most nail salon on Sunset Boulevard every year for all those years. …You can count the number of palm trees. You can see the rise and fall of Tower Records. You can see the lunch counter that was there before your favorite restaurant was there. You can watch gentrification play out. It’s an astonishing view into the history of Los Angeles.

I’ve seen the book on display and that was really, really cool for me. And then there’s the interactive piece. How did you come up with the idea of making photographs into something interactive?

Every project that we do at Stamen is a collaboration. We like to say that if only one person can do it, it’s not a Stamen project. We worked with a team of designers and design technologists to put together the work … The very first thing we did was put it on a map and see whether that was something that we wanted. So we had an interactive map with the photos on it. Eventually we kind of realized that because the experience was about Ed driving up and down the streets of LA, and specifically this one is Sunset Boulevard, the map wasn’t really all that satisfying because we’d seen a lot of maps. I think that’s a lot of how we thought about the work is we wanted it to stand out and be something beyond just, you know, a bunch of photos on a map — we’d all seen that before.

We were able to bring the Getty along on a journey with us with this idea that you would drive up and down Sunset Boulevard in a truck, just like Ed’s. We had to have a lot of conversations about: “Can we put the truck in?” “Should it be a different car?” You know, we had to have all those conversations.

One wild thing about the project is that, because the photographs are taken automatically if you drive — and I’m describing driving using the site — if you drive to a building that has a big plate glass window in the front of it, you can sometimes see the reflection of the car in the window. So it’s possible to track the changes in their cars and trucks that Ed and his team were using over the years. And really the whole thing was just informed by a desire to be really true to the archive, to not edit anything out of it, and to really give people a sense of what it was like for him to take those photographs. Because you know, this is a sort of remarkable thing about it. It’s not like a Google Maps thing. There’s no authorship of a Google Streetview.

What was the biggest challenge putting together this project?

Just think about it. I mean, the sheer volume of the material is astonishing. There are hundreds of thousands of images in there. So building a viewer that would actually be performant was tricky.

I remember a conversation with David Newbury, who’s the head of software at the Getty Trust. And he really helped us shepherd this through because the Getty is a big and complex group with lots of different stakeholders. We asked him whether — so if you’ve seen the interface, you know that you can add years, right? — you can compare in 1985, to 1990 to ‘92. And we started thinking, “Well, should there be some upper limit to how many should we allow people to use to compare?” And then David, in what I thought was a great answer, said, “Well, I don’t see why we should put any limit on it. Either you let people see only one year at a time, which is a design choice that we could have made, or you should be able to do all of them.” There shouldn’t be this kind of arbitrary, kind of “we just decided that three was the best.” So it was less of a challenge than an opportunity that we were able to really successfully, in my view, navigate.

A lot of what I think museums struggle with is they think of their collections as, you know, these kind of permanent things that are going to last forever, and the internet is not like that. And so there’s this kind of clash where it’s hard for them to meet the internet where it is. And what David was able to do is to get the Getty to take the posture that this project wasn’t [an] archive project, it wasn’t something that needed to live forever, that it had a shelf life with maybe three or four years. And then maybe it goes away, or maybe it doesn’t, but there wasn’t a plan to kind of keep this thing up in perpetuity. So that was just terrific.

Yes, that’s a really interesting point of view, the longevity of it and how long a project lives. And that leads into some of my other questions about the future of digitization and art spaces. How does that interact?

Yeah, we’re right in the middle of that right now, right? I mean, I was just trying to look at a Flash project that somebody sent me, and I’m on a new laptop, and I can’t even download it anymore. That’s the wild thing. Like I understand that they’re not supporting it, but it’s not even possible to view anymore. I’m lucky I’ve got Flash on one of my older machines, but I’ve got to go through all my old projects and figure this out because there was a lot of work done. And a lot of there was a lot of motion in it.

I think that the Getty is right. What they’ve done with this project is they have planted themselves firmly, they’ve planted a flag firmly in that space. And now they have an opinion about it, they have public work that’s about it, it’s there. I’m really interested to see what they do in the future with this, because, you know, they’re sort of pulled in these two directions of like, “The internet is digitizing everything and everything is moving so quickly.” And yet, there they are with this whole legacy of ancient artifacts. And they operate according to different rhythms and different rules.

What does a project like “12 Sunsets” add to a museum or an art institution?

I think it puts them in the conversation in a different way … They are very well-regarded in the kind of cultural studies space. And they’re interested in reaching new audiences. I think that’s a lot of the work that we do as a shop is to find people who are in a position where they’re ready to communicate about their data in a really serious way and bring it to a level of conversation that is new and exciting.

So I was really curious, whether there was more of an effort to stay true to the original media of the project — the photo book — or were you trying to add something different to it?

Yeah, that’s a great question. And, well, that was very much on our minds. The archive is really this kind of bizarrely complex thing to even think about, and I think that’s very intentional on the part of Ed. Is it an archive? Is it an artwork? Is it a historical artifact? “Yes,” is the answer, you know; it’s all those things and none of those things. And so we were very keen to engage on those kinds of questions.

“We really had to think about how to present this in a way that would be true to Ed’s vision, but add just enough to it that the internet could consume it.”

In the early versions of the project, the images were on both sides of the street, but they were both oriented upwards … But as soon as we got the images to a big enough size, we realized that … this bottom image [was flipped]. Basically, the text was backwards on the bottom ones always. And so it looked cool, but as soon as you could read the signs, you realized the other one is flipped.

So we had to really go through and carefully document all the different options that were available as far as turning the images this way, turning them side by side. We had to have a whole conversation about it. And in the end, we realized that in Ed’s original book, the images [were mirrored]. So we were like, “Oh, well, if he can get away with it, why can’t we get away with it?” So you know — I got so excited that I forgot the original question. But that was a fun aspect of the work.

That answered the original question perfectly. And then have you worked with other art-based projects before?

We have. We’ve been in a couple museums. The Museum of Modern Art has some of our work in its permanent collection… We’ve exhibited in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

SFMOMA asked us to help them visualize this really wild project that they did, called “Send Me,” where you could text the SFMOMA with a word and they would send you a picture from the collection that matched that word. It was really fun.

That turned into this really interesting conversation because it was easy to say, like, “Send me Monet,” or “Send me working-class people.” For the terms that the curators used, you could get a lot of imagery, but what would happen is that people started to get creative, and they’d say things like, “Send me annihilation,” or “Send me depression,” or, you know, whatever it would wind up being. And then, of course, curators don’t tag their work with annihilation and depression and all these things.

So I think initially, the curators were reluctant to engage with this digital team because they felt like it was distracting from their core mission. But when they realized how popular the project was becoming, then people started adding tags to their work so that they would show up in popular searches, because they wanted their searches to be out in front of people.

I think these projects can really shed interesting light on curatorial practices, accession practices — like when and where museums buy things, and from whom.

My last question really ties in with what we’ve talked about. How do you think that digital projects, like the few that you’ve just discussed, engage viewers? Do you think that there’s a different type of engagement with museums and art and digital projects? What does it add?

It lets people see the work who wouldn’t normally be able to see it. That’s one thing. Or engage with the material, I guess, is a better way to say it. I’m so bored of these virtual galleries where you go in and, you know, they just put the gallery on the internet. That doesn’t seem like a lot pointing out to me. But yeah, I think it’s largely about access and about more robust conversations between curators and the public. I mean, they’re fun to me. It’s a chance for everybody to let their hair down a little bit.

Credits for all images used in this article: 12 Sunsets