Why Jon Kasbe spent four years exploring Kenya to produce the film “When Lambs Become Lions”

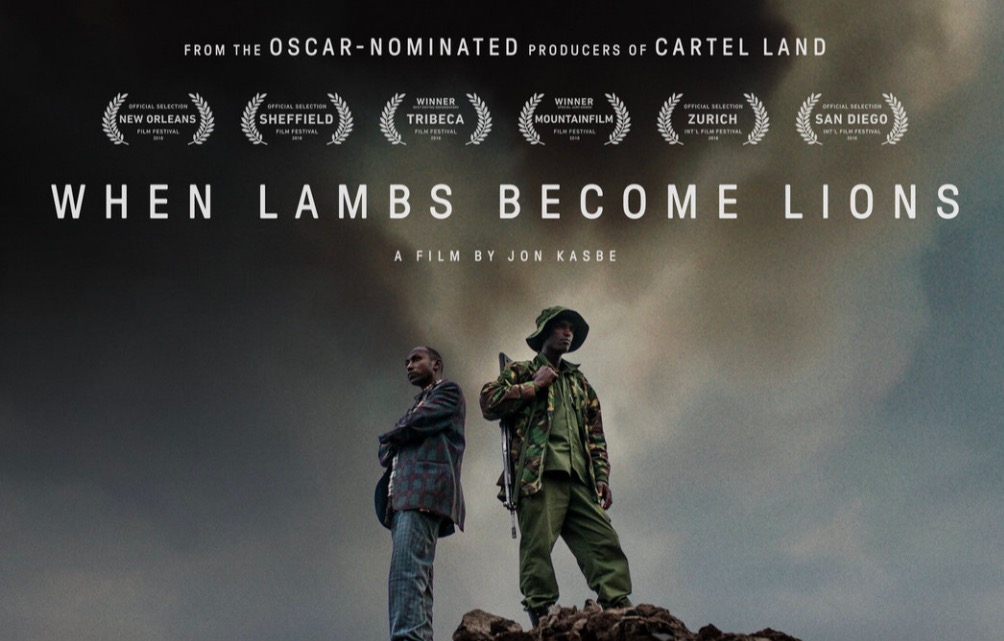

Kenya’s stunning natural beauty and the underlying cruel reality are two sides of the same coin. The documentary film “When Lambs Become Lions,” explores this juxtaposition and the value of individual life by following three characters: an ivory dealer, “X,” a wildlife ranger, Asan, and an elephant hunter, Lukas. Ultimately, the audience is left asking, ‘who gets to tell wrong from right? Evil from good?’

To quote the film’s website: “In the Kenyan bush, a small-time ivory dealer fights to stay on top while forces mobilize to destroy his trade. When he turns to his younger cousin, a conflicted wildlife ranger who hasn’t been paid in months, they both see a possible lifeline.”

The film’s director Jon Kasbe, who recently made DOC NYC’s 40 Under 40 list, spoke with Storybench about the film.

When you were 10 years old, you got your first camera. Is there a specific reason why you devoted yourself into this field of documentary filmmaking at such a young age?

Actually, it started when I was 12. For the first time, something bad happened to me in my life. Someone tried to kill my grandfather. He lived in India and it was because of the work he was doing. There had been very controversial work in a prison in a leper colony. The community didn’t like what he was doing, so he was kidnapped, doused in gasoline and they tried to set him on fire and the police saved him just before he was set ablaze. I was just a young kid at that time. I was hearing this news through my parents and I didn’t know what to do. But I felt like something needed to be done to kind of let people know what happened. So I took all my savings, raised as much money as I could and I bought a camera, then I flew to India and made a little documentary about what had happened. And that’s kind of what sparked it for me. After that, it was kind of a natural process and evolution: realizing that the camera and the process of doc filmmaking is a great way to meet people and get to worlds you would never normally get into. It’s like you can learn a lot about people and culture and life through the process. It can actually be very rewarding and not just for you as a person who’s doing it, but also for the people involved in the characters.

Since your parents worked as volunteers in a lot of different places, what was their impact on you? Did they support you?

No, they actually didn’t want me to do it. It was a different time now than it was 10 or 15 years ago. I didn’t grow up in a wealthy family. My family was actually pretty poor. So to them, me running around with a camera, trying to make little videos, they didn’t see that as a way for me to ever find financial independence or to create any type of stability. I remember early on, when I was going to college and I was saying I was still doing it, my stepmom would joke, “You know, John, there’s a basement in our house but it’s not for you. You might want to think about getting a minor in business or something like that.” But eventually they came around, I think they saw that I really loved doing it and then they saw that I was finding ways to not go in the bread while doing it.

A lot of filmmakers talk about how hard it was to make their first film because they did not have any support, but I know this film is not your first film. You already had a track record. Is your situation going better now?

No, I think that’s the situation for most filmmakers and creators in general. It’s really hard to find money to do the projects, especially when it’s a longform project like this. We spent almost four years making this and it’s a film that doesn’t have a clear call to action at the end. Especially, we’re not necessarily trying to change the situation, we didn’t go through this process and come out with a solution. We want to show a perspective that we felt like hadn’t been seen before. To find companies and NGOs that did want to support this project and have that message aligned with what they’re trying to do, it’s a tricky thing. At the beginning, I used to be a kick-starter, so I raised money to take it out there and to start building relationships with all the characters. Then I did some shooting and I cut together a two-minute reel and a deck. I started pitching it to everyone that would listen to me. There’s one company in particular that I pitched it to call the documentary group. From the very first meeting we were in, they loved it. They wanted to be a part of it. They said, “Let me know what you need to keep going.” It was awesome they came on board. Our main investor is a company called Fusion and they’re the ones that really made it possible financially for us to spend so much time embedding and then spend so much time on the deck, which was a testament to them. They saw the value of the project and saw the importance of it in the time.

You said you always wanted to be an outsider for this documentary without any impact on the character’s life, but your first documentary was about your personal life and your grandfather. I wonder why you changed your position? Or have you changed your position?

I know that my position changed. I think I was 12 then and now I’m 27. I think I did that story and now move on to other stories. I think with documentary film, you have to be really careful, especially when you’re going into a place that’s not your own. I think at the beginning with my grandfather, that was a natural way for me to get started. It was a space I felt comfortable within. It was people that I knew, that I trusted and also trusted me. The process of gaining access wasn’t really a process because they were family. It was a great way to kind of dive in. It was a great way to start. Now is different.

When I started this project, I wasn’t looking to go and tell a story in Kenya. I wasn’t trying to find a way to impact the conservation. What happened is I’d done three other projects in Kenya before this. I had friends there that were telling me, “Hey, every story that’s coming out of here and conservation of saying the same thing – they’re all playing this good versus evil story between poetry and rangers. But the reality is very, very different.” My response was, “You guys, that’s great, but I don’t really feel drawn to that, doesn’t really feel like that’s my story to tell, you guys should go do it.” And then they pushed back there and said, “Just come and meet ‘X,’ sit down with him and tell us you don’t want to spend time with him and make a short film about him.”

So I went there, I met “X” and “X” blew my mind. He’s not at all what I expected. He wasn’t ashamed of what he did. He explained it in a very clear, concise way and it made sense. He was saying we kill elephants to survive and to feed our families because it was taught to us by our parents. “We think of it as an art, the process of creating this poison and tracking the elephant for weeks and all those things. But if you looked at what the rangers are doing, they’re killing humans. We would never do that.” These words grabbed me, I hadn’t really thought about it that way. “X” said, “There’s a shoot to kill policy out here: if you get caught, you’re killed. I will never kill people, that’s just something I will never do. It’s just so bad.”

It started to kind of crack at my understanding of the situation and I found myself not able to stop thinking about it. I found myself wanting to listen to “X” and trying to understand the way he sees the world and the way he navigates it. I kept spending time with him and kept trying to understand, listening. I didn’t feel like this was my story, and it wasn’t.

Throughout the process, I think motivation was a really key thing to be aware of. That was really important to me that “X” and Lucas’ motivations from being a part of the project because they wanted to be a part of it. They wanted their story to be shared and they felt like I did. They were actually the ones crafting it by allowing the end. So, although they’re not the ones telling me where to put my camera and they’re not the ones in the edit room, they’re the ones that are opening it up and trusting me with it. A lot of times when we were in making decisions, it wasn’t that much about what do I think is the best way to do this, but what is like the most honest representation of the experience in the field.

How did you come up with the title “When Lambs Become Lions?”

Early on in Kenya, there was this problem that an empty stomach will turn many lambs into lions. Throughout the process that quote stuck with me, I felt I had so many experiences pointed back to that idea that when we humans are pushed into a corner where we’re all kind of the same and we’ll do whatever we need to survive. At the same time, it’s a title that I feel like a symbolized transition which I kept finding so much with our characters. It also allows the viewers to kind of find their own interpretation of it and apply their own meaning to it. What is more, it’s a catchy title which we definitely wanted.

I noticed that you have so many visual metaphors in your film. For example, after the scene of the character’s dilemma, there was a scene of two goats fighting each other. So, did you plan to have these establishing shots beforehand? Or did you make those decisions in the editing room?

When I was shooting those things, I don’t know where they’re going to go in the story. Those kinds of visual poetic moments. I really just captured the texture of the place and being aware of the feel of what’s happening in the world of the characters. Over the four years of shooting, I would just film anything that captured my attention. Then in the editing process, we found a huge amount of animals in the spaces of all different types, oftentimes eating something. It was interesting because it took us a while to realize it. Then we thought about in so many of our transitional moments between scenes are these animals eating something. If you zoom out a little bit, you would realize there’s not any scene of the humans eating. The human does not eat in the movie which is a representative of the experience. They didn’t eat very much. They were chewing a lot on this plant called Mira and it was a stimulant that gives them huge amounts of confidence and keeps them up for days at a time, but also removes hunger so they wouldn’t have to buy food. It is what they found to be something very helpful when they’re trying to work but also when they don’t have money to buy food. That’s part of the meaning behind the scene. I feel like a lot of people missed it, but there was a layer of meaning in those beautiful moments.

How did you get the characters in the film to be so open with you while they were in front of the camera?

It was interesting because in that moment, I was doing nothing. I think the real answer is what have I done before that moment that made that moment happened, so he wasn’t thinking about me, but he was actually living his life in the moment. I had been there for huge amounts of time and been really patient and waiting. I was kind of doing everything I could to make myself a part of their daily lives so that when those moments that were meaningful, when those life changing things, like a birth or a death and things like that happened, it was about that and it was not about me. It’s like the foundation of a house. It’s like we got this house here and there’s a hurricane coming in. The house doesn’t get blown over. How did the house not get blown over? And it’s because five years ago we built a really strong, sturdy foundation. Because we did it properly and we did it authentically, and we did it with honesty. It is the same kind of thing. My relationship with these guys from the beginnings, it was very straightforward. It was very clear and we built a real friendship that is going to last for the rest of our lives. I still talk to these guys every day and it’s not the business. The film was great and I’m really glad we made it. It was important, but I can’t tell you how many times the relationship was more important than the film.

How did you deal with being behind the camera but also wanting to help those in front? And was working with the crew?

There were many times, especially in the first two years of shooting, where money became an issue. These guys are on the brink of poverty and I’m coming in as an outsider of the camera, so there’s always a gap there. There would be all types of situations where they’d want me to use my money to kind of fix their problems for the day. But it was really important to me that they were motivated to be a part of this film and to give me access to see what was going on. I always stayed true to them and so I never paid them. That was really hard for them. For them, it’s a tricky and a hard thing to understand.

Of course there were definitely points where they said, “You don’t care about us, you don’t love us, if you’re not willing to pay for this, you clearly don’t care about us at all.” And then they would quit and they went away. I wouldn’t hear from them for two weeks, four weeks, six weeks, and they’d say, “We’re done with the project. It’s over, you’re not our friend.” All kinds of stuff like that. It was really hard for both of us, but it was important to me to stay true to it and respect the parameter we’d set up for ourselves. At the end of the day, they’d always come around. They’d always come back and said let’s continue working together.

It was tricky and at the same time, it’s not to say that there was a hard line throughout the whole process. A great example is when Sam’s wife was giving birth, I had a second shooter that was there with Sam that captured his moment while I was with “X” at the house. The secretary called me, “I’m running with him because the situation. He is really worried that he’s not going to make it in time and that his wife is going to die in labor.” Suddenly, we had the choice where I was thinking about do we let him run the four hours it takes to get home or do we send a car to go pick them up and bring him back so that if something happens to his wife, he’s here for it. I called a car and they sent a car to go pick them up. It is kind of a situation by situation thing, but for me it was really just about approaching each of those situations with honesty and transparency.

Sometimes when they would do these things just like a little bit of a test, I think they were testing me to see how far will Jon stick to what he said, or will he crack? If I had paid them in those moments, I think it would have been assigned that the film was more important than the relationship. But I think by not paying them, I showed them it’s not all about the film. I also found many other ways to show them that I cared about them outside of money. I won’t tell you the number of hours of babysitting I would do or the amount of meals I would cook. At the beginning, they barely spoke English but by the end of project, they’re fluent in English. I taught them all how to type on keyboards, a lot of things like that. You need to spend a huge amounts of time to create that bond.