How the California Academy of Sciences launched bioGraphic, a magazine illuminating the natural world

Bursting with flashes of yellow, ring-necked parakeets fly across the screen; just a click later, globs of slime mold create sprawling networks, consuming your device. With vibrant images and compelling content, San Francisco’s California Academy of Sciences launched bioGraphic, an online magazine dedicated to exploring natural phenomena, hoping to inspire conversation about – and solutions for – the planet’s most urgent environmental issues.

After spending a year in development refining the outlet’s scope and media formats, a team of editors, directors, and designers selected a digital publishing platform called Storied that enabled them to customize their online presentation of immersive and innovative stories. With Storied, bioGraphic is able to publish photoessays, short articles and multimedia-infused long-form storytelling.

After spending a year in development refining the outlet’s scope and media formats, a team of editors, directors, and designers selected a digital publishing platform called Storied that enabled them to customize their online presentation of immersive and innovative stories. With Storied, bioGraphic is able to publish photoessays, short articles and multimedia-infused long-form storytelling.

BioGraphic’s editor-in-chief is Steven Bedard, a former field biologist with a specialty in spotted owls, northern goshawk and sharp-shinned hawks who translated his affinity for animals into a career as a science journalist whose writing has appeared in Scientific American and other publications.

Storybench sat down with Bedard to chat about bioGraphic’s storytelling mission. Stephanie Stone, bioGraphic’s editorial director, and Andrew Zuckerman, a filmmaker and photographer who has contributed to the magazine, joined the conversation, too.

Could you walk us through how bioGraphic materialized?

Steven Bedard: It’s been about a year and a half in the works from the time of its inception until the time we launched in April. It grew out of a larger set of initiatives that began at the Academy. Jon Foley, our director, wanted us to focus on what we would be known for for the next twenty, thirty, forty years. So he put this call out for big idea proposals.

A group of us put together a proposal about improving science communication, and a piece of that was starting our own publication independent from PR tools and the institutional site – we wanted an independent publication. And that ultimately became one of the big ideas that was greenlit. This is nontraditional education – it’s a publication that serves to improve science literacy.

How do you incorporate your research background into bioGraphic’s mission to improve science literacy? And what does this outlet do for the scientific community?

Bedard: I think scientists are starting to recognize that getting the word out, whether through social media channels or publications and blogs, that that’s what changes people’s perceptions. That’s what gives a piece of research an impact that it’s not necessarily going to have by publishing a scientific paper.

We are one outlet that is serving the need of getting stories out there about things that aren’t necessarily newsworthy, content isn’t driven by the news cycle. If there’s a news hook, we’re looking for the broader trend to tie pieces together. We’re also looking to tell process stories and stories from the field, help readers understand that these scientific endeavors take time and have ups and downs.

So would you say that’s kind of bioGraphic’s goal in a nutshell? To reveal these stories, including the triumphs and downfalls of science research, that aren’t really being told?

Bedard: Yes, of course it’s hard to put a project like this with so many moving pieces into a nutshell, but I would say that’s a good characterization of it: Stories that aren’t necessarily being told about the process of scientific research and conservation. We are really looking for stories that provide hope and inspiration, we don’t want to be doom and gloom. But we also want to be realistic and talk about the very real environmental and sustainability challenges that are out there.

Stephanie Stone: One of the things we saw when thinking about what we could add to the landscape was that there was really interesting immersive and innovative multimedia storytelling by The New York Times, The Guardian. But very little of that innovation was about science and natural and environmental topics. That felt like a sweet spot for us. We want to tell stories on topics that weren’t followed up on after their news cycle ended, and in different ways. We want to use powerful imagery and creative storytelling techniques to get people interested in things they might not otherwise be interested in.

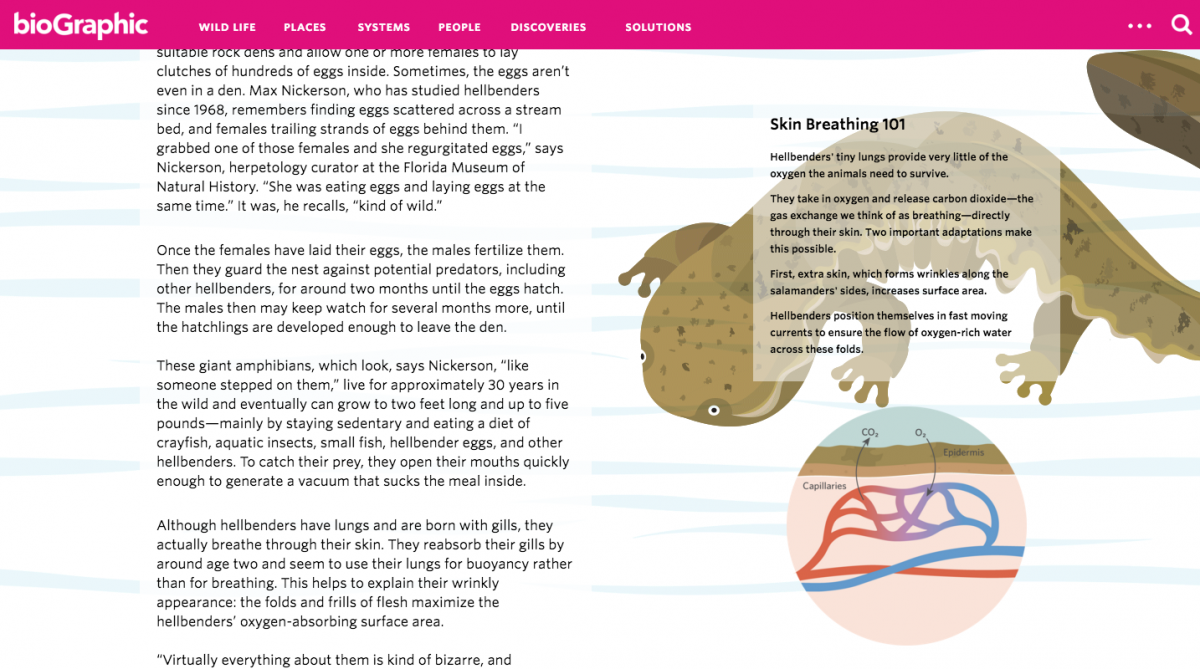

Speaking of these moving pieces, the stories uniquely incorporate video, photo and text and displays these components in interactive ways. How do opportunities for multimedia presentation play into the publication of a story?

Bedard: It’s a real challenge, maybe that’s the other part of it, of why you don’t see more outlets doing this. It’s hard to do, and it’s hard to do well. It requires an investment of dollars but it also requires the investment of time. You need the time and the expertise to be able to add those elements to a story in a way that compliments rather than detracts from the story. So that’s first and foremost.

Basically our workflow at this point is we vet pitches, we agree to do a story and assign it, and that reporting and writing needs time, but we don’t want to wait until we have a draft before we start working on the media. So we have a parallel process where while the reporting is happening we are also developing these media elements. It’s relatively simple when it’s photographs, it’s harder with a richer, more complex piece of media.

Can you talk about how you published “An Audacious Plan in the Twilight”?

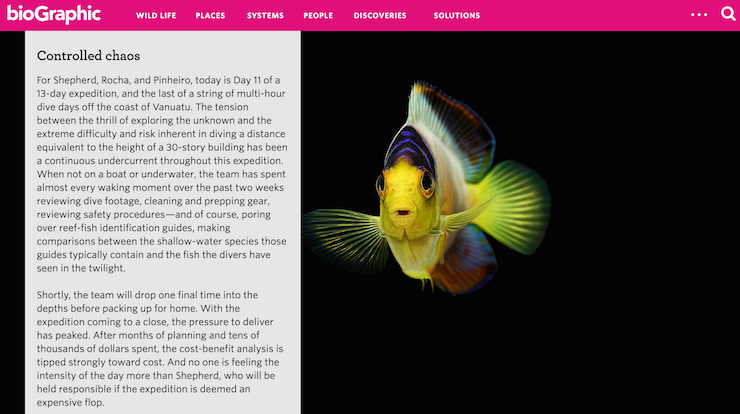

Bedard: From the very beginning we knew we wanted to do a story on twilight zone research and exploration, and we have a team at the Academy that does that. We decided early on that bioGraphic wouldn’t only be about the Academy and that the majority of our stories would be about others, but that we also won’t ignore good research going on here.

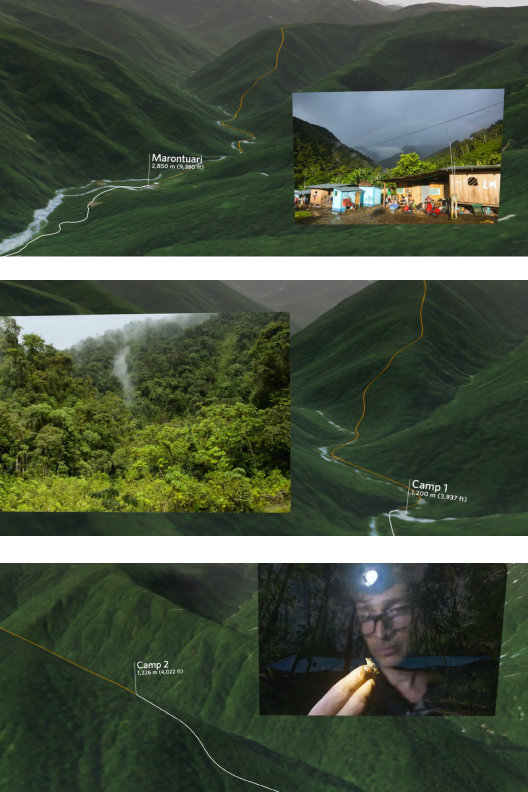

It was just luck that Andrew Zuckerman was looking for a project to work on during his fellowship at the Academy. Being able to see unbelievable morphological characteristics of these creatures in these high resolution images  that Andrew creates, and getting the personality of these organisms, we thought how amazing that would be. And the final piece of it, as we were thinking about immersive stories and what works well – like The New York Times’ El Capitan piece – we thought how great would it be to get data to create the dive site in a 3D model. And as the reader is reading the story they are seeing the divers’ route in and back.

that Andrew creates, and getting the personality of these organisms, we thought how amazing that would be. And the final piece of it, as we were thinking about immersive stories and what works well – like The New York Times’ El Capitan piece – we thought how great would it be to get data to create the dive site in a 3D model. And as the reader is reading the story they are seeing the divers’ route in and back.

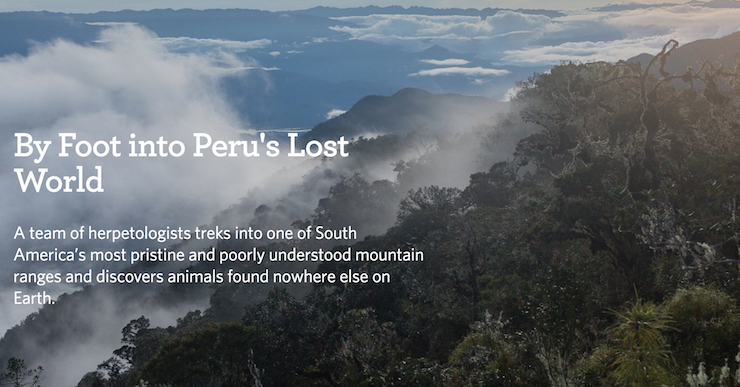

It wasn’t easy to get that bathymetry data – it was difficult to get the Vanuatu government to release that data. But we were finally successful and with help from our colleagues at our planetarium we were able to create this element that displays video imagery data as the divers’ route – you couldn’t really visualize it any other way. We have another piece like that that we’ve just published based on Peru’s Vilcabamba mountain range.

Andrew Zuckerman: I’ve always been interested in the convergence of art and science. Whenever artists and scientists have come together, really interesting things occur. But I never expected to play a teeny part in the science, which is what happened when I was there.

We started to get to work and creating these pictures, and a veterinarian came over and said “Oh wow, can you zoom in on that?” And because of the resolution, that sort of crafting of our images, they were able to see things that they couldn’t otherwise see. At one moment there was a spot on one of the fish that they would normally have to do a scrape on, but we were able to blow up the image large enough that he was able to figure out what that was without affecting the fish, which there was only one of. It was a moment where I thought imaging these things plays the teeniest part in their ability to identify and understand issues.

What is the largest technical challenge with bioGraphic?

Bedard: We’re trying to push the envelope as much as we can with media while balancing between page weight and performance and user experience. Then, you add mobile and tablet and making it look good on all devices and it complicates things a lot. For that final product to work and make sense to the reader is hard. It’s as much an editorial challenge as a technical one.

Can you tell us a little more about the Storied CMS?

Bedard: Our website is custom built by Storied, based here in San Francisco. It’s HTML5 and uses frameworks like Angular and jQuery. When we started working with them, they said “We want to create a CMS that allows publishers to create a Snow Fall experience without knowing code.”

This may be far too big a question considering how recently you launched, but where do you hope bioGraphic will go? What vision do you have for what the outlet might achieve?

Bedard: It’s actually a fairly easy question to answer. I feel that we’ve only scratched the surface. This is a pilot and it’s a great opportunity, I think we’ve got a great start and I think there’s just so much more that we can do.

And so my one-word answer to your question is “more,” and what I mean by that is more great stories from cool places and about cool organisms and adaptations and phenomenon. We’re also trying to produce a somewhat higher volume of stories, and more of the media that compliments our stories. Our media not only distinguishes us from others who are out there, that’s a side note, but what we want is to give readers the richest experience we possibly can.