How The Economist’s Espresso app goes beyond headlines to provide a daily shot of news analysis

Brevity is indispensable for news organizations looking to break into the ever-growing market of mobile readers, but telling complex stories in confined character counts is still an emerging science.

Linking back to full-length articles is often the easiest way to package content for social media and briefing-style newsletters while still promising readers analysis and context. But for the team behind Espresso, The Economist’s six-day morning edition, the challenge is to present complete stories in 150 words or less.

Linking back to full-length articles is often the easiest way to package content for social media and briefing-style newsletters while still promising readers analysis and context. But for the team behind Espresso, The Economist’s six-day morning edition, the challenge is to present complete stories in 150 words or less.

“We try very hard not just to present a single facet, not to just present a single news-line but as deeply as is possible to contextualize,” said Espresso co-editor Jason Palmer. “If you wanted straight reporting of the news you’d go to Reuters. This is The Economist voice distilled down from the sort of thing you’d get in print.”

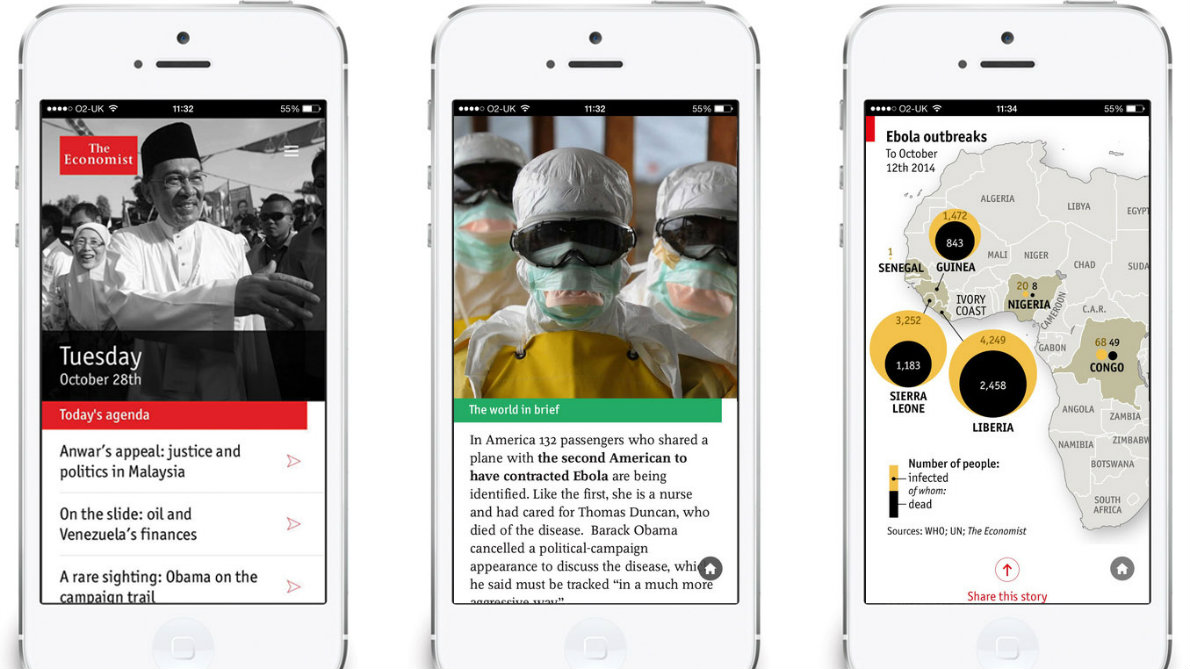

Launched in the fall of 2014, the app gives readers five small stories a day, plus a handful of news snacks and a quick take on markets and currencies — all adding up to one strong shot of news analysis.

Storybench spoke with Palmer about the ways Espresso avoids reheated news headlines and simplified narratives in short-form, digital storytelling.

What’s changed with Espresso since it launched in 2014?

One of the more interesting things is that there wasn’t always a Saturday edition. The CMS that we use permits us to do surveys, so the editors did a reader’s survey and the response was very clear that people wanted more sport and more science. Because there’s always plenty of content to cover during the week, the way we’ve dealt with that feedback is including it in a Saturday edition.

Each edition has five 150-word pieces and seven little nibs, little 60-word news pieces. The five on the Saturday edition are three culture, one sport and one science. That was straight out of what the readers wanted.

In terms of other changes — I noticed when you launched the app that it wasn’t linking to full articles that were connected to the stories. That’s something you do do now.

Yes, at least one story links to a bigger piece. The idea is not just to link to the latest thing, but to link to a meatier thing, a more substantive thing. When we do special reports and briefings they often link to columns like Free Exchange because they offer deep analysis. The idea is not, as you might have at the bottom of a BBC story, to present ‘the last three stories we did on this.’ It’s quite targeted towards readers who are only going to click if they really want to learn more.

That’s a fairly significant difference between what we do and what a lot of the other newsletters and daily briefings do. There is a long-standing, rigidly maintained culture of ”finishability”. It’s a widespread concept, but one that we either pioneered or fly the flag for. The idea is we’re going to give you something that you can read, finish and feel like you’re done.

In terms of The Economist being a weekly publication and Espresso being daily, how does that work in terms of workflow? Do you feel like you’re working to generate content for the next print edition as well?

This plays into another big change that was made. When it started, Espresso was rigorously stories for the day, so we were publishing in the evening for the forthcoming edition.  That’s a very hard thing to do without manufacturing some pegs sometimes. We’ve since loosened that a bit, and in truth it’s a real mix in terms of the hardness of the pegs.

That’s a very hard thing to do without manufacturing some pegs sometimes. We’ve since loosened that a bit, and in truth it’s a real mix in terms of the hardness of the pegs.

Sometimes it’s clear, so “the federal reserve is meeting tomorrow” or something like that, and sometimes the pegs are just launching pads for broader analysis. We’re not in the news business. We’re doing the very Economist-y thing of taking a step back and taking a wider look.

For instance, there’s the ongoing story about transgender bathrooms in the U.S. We went casting about, and there’s going to be a meeting at state-level of some activists. We know that’s coming up, we have a peg, and we can use that as a peg to talk about this broader story. A lot of the pegs fit that description.

Could you tell me about an average day on your job?

The European edition goes out at 5:00 in the morning, so the first thing is to make sure everything’s alright with the European edition. At 11:00 a.m. the American edition goes out. For the news nibs, or what we call gobbets, we make sure those are current news because things can shift overnight.

To a degree there’s a little bit of regionalization because we have the Asia edition, the European edition and the American edition. Those are largely overlapped, so sometimes we regionalize, but rarely more than swapping out one or two stories. The gobbets are a lot more flexible, not least because news is changing and the most important thing in a region might change or shift its position on the list.

For the most part we’ve already commissioned what we expect to come in for the next day’s edition because the first one that goes out is Asia-Pacific at 9:00 p.m. London time. We have the rest of the day between 11:00 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. to get that together. When we finish in the evening we hand off to Washington and they have a good look at what’s there, and in principle they can redo or adjust the pieces in the case of a big story, but that’s quite rare. Washington hands over to Delhi or somewhere thereabouts in the world, and then they take a look at it and make any changes for the European edition.

We also have to get a chart going. The Economist is known for its charts and we have an absolutely excellent graphics team, who in combination with our excellent research team can come up with really excellent ideas for how to tell stories through graphics. We commission that, commission the pictures, rattle the cages of writers — from there it’s your usual story.

The fun at the end is what we call the zinger, or the quote that’s at the end of each edition. More often than not it’s a quote from someone who either was born or died on the day of that day’s edition, or sometimes just a particularly juicy quote that is directly relevant to one of the five pieces.

Are writers for Espresso the same writers for The Economist’s print publication?

Yes, all writers and stringers. If someone’s writing a lead note for the financial section about a federal reserve meeting, for them it’s a fairly low marginal cost just to do a 150-word version. We also get a lot of contributions from stringers in the field.

I quite like it when it’s funky little pegs, when it’s not big enough to merit a story in the print section but it gives someone a jumping-off point for analysis. They’re often the sort of thing you’ll only get from people on the ground, and I quite like the sense that we’re getting a view from the ground somewhere rather than just looking at the wires and turning something over on the basis of that.

Has it been easy for writers to transition to writing shorter nuggets for Espresso?

Ours is not your standard newsroom and the culture shift, as many people in the business know, from doing a weekly print product to feeding the hungry news machine of today is a difficult one. For every legacy media operation, for every print operation finding its way with multimedia technology, with apps, with newsletters, with short-form video, they’re turning the screws to journalists who may not have had to deal with all of these different media formats in the past.

You do get some resistance from some people who suddenly feel quite pressed in a way that they weren’t before, but it’s very clear that Espresso is becoming, or already is, a flagship product for us. The editor-in-chief has been very clear that it is just as important to write for us as it is to write for print. That’s a hard message to get across I suppose because everybody wants to see their piece in print because that’s always been the lynchpin of the whole operation. But this is just one aspect of a broader cultural shift that’s going on here and everywhere else like here.

Are there changes you are looking to make going forward with Espresso?

I think changes that are on the horizon are more about protocols than content. This has been run like an internal start-up for a long time. The people who work on it are major workaholics. It’s very involved because each piece is a story in its own right, with charts and fact-checking and what have you. It’s not actually that much less work to make a 150-word story than it is to make a 600-word story when they’re just as fleshed out with all the bells and whistles. It’s a considerable amount of work and especially if you’re regionalizing.

The ethos has been that the finished product is made in London and changes can be made elsewhere in a pinch. I think probably more responsibility will be delegated to other regions, and more people will be on the hook for it more formally to actually produce content, rather than keeping everything jealously guarded in one small office with two overworked people in London.

- Four Tips on Gamifying Journalism From Al Jazeera’s Juliana Ruhfus - October 4, 2016

- Tips and Tutorials from London’s Journocoders Meetup Group - September 1, 2016

- How one digital humanist visualized the shapes of 50,000 novels - August 10, 2016