A new AP report charts the future of immersive journalism

The revolution will be immersive.

Journalists today have a suite of new mediums at their disposal with which to tell stories that not only engage audiences but also allows news consumers to explore and create their own narratives. That kind of dynamic storytelling is the future of journalism, according to Francesco Marconi, a strategy manager for the Associated Press, and Taylor Nakagawa, an emerging media fellow at the AP.

Marconi and Nakagawa today published a comprehensive guide to immersive journalism titled “The age of dynamic storytelling: a guide for journalists to immersive 3-D content.” Dynamic storytelling, they argue, is a new approach to journalism that puts the news consumer at the center of the story. By leveraging technology in innovative ways, Marconi and Nakagawa write, journalists will improve their ability to shape perspectives, influence popular opinion and inform the public.

In a sense, these new technologies – like 360-degree video, augmented reality and virtual reality – represent a shift in the industry from passive to active consumption. Traditional journalism is largely told from a single, fixed perspective, Marconi and Nakagawa argue. Print, documentary films and photographs are all passive methods of consuming news. Immersive content, on the other hand, has created an interface whereby audiences can actively participate in the news they consume.

Marconi and Nakagawa reached out to dozens of industry leaders in journalism, technology, academia and entrepreneurship for specific areas newsrooms should consider when constructing a non-linear immersive experience. Considerations like including audience participation, the immersive technologies available and the various perspectives presented.

The authors identify three immersive stages: 360-degree video, augmented reality and volumetric capture, which includes computer-generated imagery and 3-D scanning.

- 360-degree video: The majority of 360-degree video – so-called monoscopic video – is captured with a single camera or camera rig. While the spherical image provides a sense of immersion, clarity decreases at the edges of this sphere. Take the AP’s “House to House: The Battle for Mosul,” a 360-degree piece that transported viewers to the front lines of the battle against Isis in Iraq. “Compared to a still photo assignment, 360 is the ideal medium for combat,” Maya Alleruzzo, an AP journalist who produced “House to House,” tells Marconi and Nakagawa. “The stills were good, but couldn’t really capture the scene like the 360 images.” With stereoscopic video, on the other hand, “a pair of 360-degree camera lens are placed side by side to add depth between the foreground and background for a heightened sense of immersion.”

- Augmented Reality: With AR, 3-D models are projected onto physical surfaces using depth sensors built into the cameras of mobile devices. One example of this is The Washington Post and Empathetic Media’s AR experience of Freddie Grey’s death in Baltimore, which required an app to be downloaded.

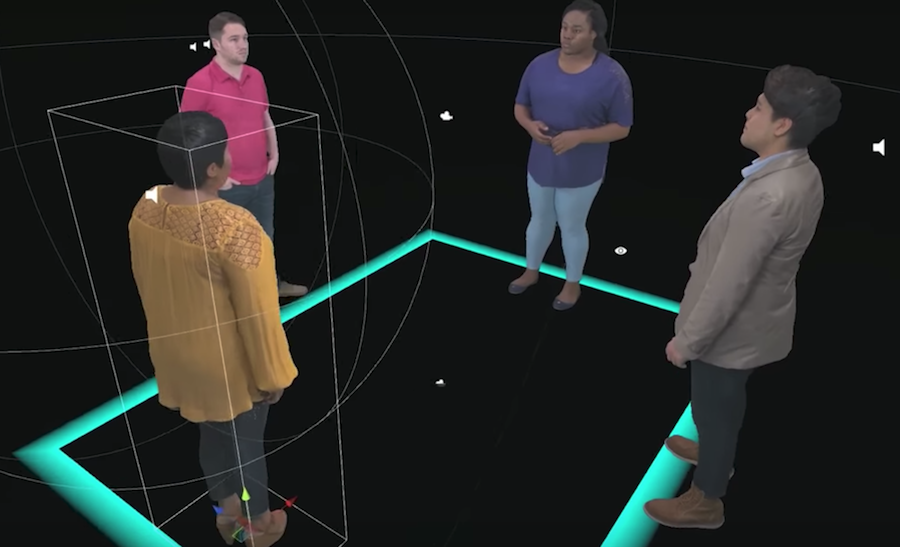

- Volumetric capture: Using thee-dimensional scanning technology – pioneered by companies like 8i, which uses dozens of cameras to capture 3-D holographic video – newsrooms may soon be able to capture people, buildings and entire environments and convert them to photo-realistic scenes that news consumers can then interact with using special equipment, such as VR headsets and gloves fitted with sensors. These vibrant 3-D models will give audiences an even greater sense of depth and texture than they’ve experienced with 360-degree videos. Enabled by volumetric capture technology, virtual reality users will soon be able to not only “walk” through virtual spaces, but also touch and interact with 3-D objects and people — immersing audiences deeper into stories. “Out of Exile: Daniel’s Story,” an immersive story about a man coming out to his family, was produced by immersive studio Emblematic Group using 8i’s technology.

Finally, in order to measure participants’ engagement with dynamic storytelling technologies, the AP also conducted a study with neuroscientists at Multimer to look at brain activity – in the hopes of measuring attention and relaxation – of 12 study participants as they consumed immersive media content at NYU’s VR laboratory. One thing the study concluded was that hands-free headsets drove higher levels of engagement that cardboard 360 viewers. Counterintuitively, though, cardboard viewers elicited high levels of stimulation, the authors write, because of the high quality of the images.

Marconi and Nakagawa’s report challenges journalists to relinquish control of how news is traditionally told and to think more about how news can be presented in different ways. That means considering things like ethics and standards, newsroom workflows, technology deployment, skills and user adoption, the authors write. At the very least, the report should provoke a discussion as to how newsrooms will integrate strategies and tools to produce and distribute immersive media across devices.

Nearly all journalists agree that immersive content and non-linear storytelling techniques have many facets and there are many ways it can be implemented in a newsroom. But like any other technology, the more you know about a tool, the more effectively you can use it.

Reading this report will no doubt be a first step for many newsrooms.

- Behind the scenes of an augmented reality app that’s visualizing a world after sea level rise - October 18, 2017

- A new AP report charts the future of immersive journalism - September 26, 2017

- How The New York Times is looking at climate change through a new lens - March 31, 2017