Using maps, kayaks and notebooks to understand the biodiversity and resilience of Boston’s coastline

On the campaign trail, presidential candidate Donald Trump talked a lot about revitalizing America’s crumbling infrastructure. Other issues, however, have since crowded out the monumental task of addressing this aging infrastructure. But for scientists like Northeastern Marine Science Center graduate student Ashley Cryan, infrastructure and how it affects the health of coastal ecosystems is a daily preoccupation.

Cryan and her colleagues in Professor Brian Helmuth’s laboratory are looking at the effect on biodiversity of armoring our coasts with structures like concrete walls, dams, jetties, or rubble dikes. At the heart of her research is a question that society does not always consider: What are the ecosystemic effects of the materials used to protect cities from storm surges and rising sea levels? Cryan, for one, is optimistic that America can adapt its structures to become more hospitable to valuable organisms, like mussels and clams, which filter pollutants, or coastal vegetation, which buffers storm surges. Shes’s also interested in understanding the protective role played by hybrid living and man-made infrastructure – so-called “gray-green infrastructure.”

By studying and visualizing the environmental impacts of installing shoreline infrastructure, Cryan hopes to understand the implications for coastal communities in Boston and beyond.

What is coastline armoring?

I don’t think I knew what shoreline armoring was when I started grad school, so I think it’s a very fair question! Essentially it’s the technology, physical structures, and (in the general sense) infrastructure that we use to harden shorelines for development. So, it’s anything that you would see along the seaward edge of a parcel of coastal land. This can include bulkheads, or vertical walls typically made of concrete or corrugated steel. [The Newport coastal walk is a great example of this idea.] Another example is something called riprap revetments, which is comprised of cobble and stone that are set along a linear stretch of shoreline. They’re less structurally sound than a vertical wall would be, so they’re used for low density development areas. This practice has been going on for a long time all around the world, and it’s generally done to stabilize land or to protect it from coastal erosion. Recently we’re seeing more and more structures meant to protect from coastal flooding. So that’s more of a bird’s eye view on the topic.

How I like to think of it: In comparison to the sort of gradual and shifting of a natural or unaltered coastline, this kind of infrastructure looks like someone has gone in and traced the coastline for sake of onshore functionality. My place in this work is quantifying the ecological impact of these spatial developments.

What got you interested in this kind of research?

I’ve always had an interest in working in an urban context, and I have a really great PhD committee that has encouraged me to pursue this specific avenue. A lot of their work has laid the foundations for what I’m studying. My advisor, Brian Helmuth, is an ecophysiologist and the premise of his research is looking at the world from an organism’s point of view, and specifically looking at how climate change will affect these organisms on a very local scale, even on a microscale. This work got me thinking about how artificial infrastructure serves as habitat in cities, recognizing that the variation in habitat complexity is homogenized and reduced when we put something like a concrete wall in place of a salt marsh or a rocky intertidal ecosystem. Natural habitats have a lot of places for species to weather the storm, so to speak, during extremely hot days or dry periods. There will be steady pockets of shade or water in those places to provide refuge, where there really are not along an artificial, vertical wall.

Another one of my committee members here at Northeastern, Steven Scyphers, has done really interesting work with coastal homeowners and their decisions for coastal shoreline armoring. He actually found that one of the biggest predictors of which technology homeowners decide to install along their shoreline to stabilize it is looking at what their neighbor did. I really like thinking about these social variables alongside ecology, looking at the physical habitat space, and how that impacts what kind of community assemblages we find living in it. Further, I like looking at such an extensive practice (armoring) and considering the human side in understanding why we continue armoring shores, even at this time, when know that climate change is posing greater and greater risks to coastal areas and growing populations.

Another person that has influenced the development of this project is Dan Adams, who is the director of the School of Architecture at Northeastern. I was in his course, The Design of Urban Shores, where we talked about this complexity of human beings’ relationship to the waterfront and how, especially in Massachusetts, that’s a public right. We discussed the many ways that we, as a society, are going to have to confront the realities of climate change and how these decisions will impact not only our intrinsic relationship, but also our physical relationship with the water through our built infrastructures.

So, it’s all these different angles and overlapping subject areas that make me interested in this.

What are the ways you and your team intend to visualize your data?

I think that’s one of the cooler things I’ve been allowed to do and that Brian [Helmuth] has supported me in! Last summer we created a virtual tour of Chelsea Creek. It’s a 360 degree video that is publicly available on Vimeo and basically allows anyone viewing it to virtually access this very restricted landscape. These waterways have really interesting heritages and we’re trying to find ways to help people to feel more connected to them. At the moment, especially in Chelsea and East Boston, which are the predominant communities that border the waterway, you could talk to people that have lived there their whole life and some say they didn’t even realize they live right next to the water. That’s how dense the commercial-industrial activity is on the waterfront. That’s probably one of the coolest visualizations. At the same time we also created photo spheres of Chelsea Creek and published them on Google Maps. Those have been viewed over 10,000 times since September. So, I think it’s kind of understated here that people are really interested in getting access, even virtual access to this waterway.

How are you quantifying the integrity and health of the coasts around Boston?

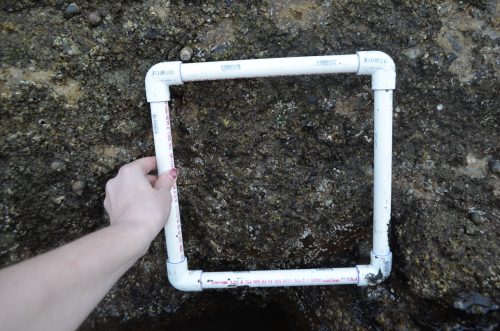

I have sites along Chelsea Creek, the lower Mystic River, and Fort Point Channel. So, what the work actually looks like is myself and my summer intern Jack out there clinging to walls (these bulkheads) and using some tools to approximate the percentage of cover that these invertebrates make up along the walls. We have a good time out there. Basically we’re looking at two metrics of biodiversity: species abundance and richness. We use a quadrat, which we layout and use to take a subsample of a population and estimate what the proportional abundance per species is across the whole survey site. There’s a lot of research on how biodiversity affects ecosystem function and stability, which is why we’re looking at that metric as sort of a proxy for ecosystem health. Although, I would say we’re at the beginning stages of evaluating what sort of state these sites are in, they’re very simple at the moment. At the present it’s mainly just barnacles, algae, littorina snails, and some invasive oysters.

How does the health and biodiversity of the intertidal community directly affect the coastal cities and residents of Massachusetts?

That’s a very important question to consider. There’s a couple interesting examples to look at. Boston was originally a salt marsh ecosystem, so we had vast expanses of all kinds of marsh grass, ribbed mussels and a whole community that is associated with this kind of environment. However, we’ve developed our coastline so extensively, we have hard infrastructure in its place. That kind of physical object doesn’t really exist in nature, there’s no corollary in a salt marsh ecosystem. And so, I try to look at what kind of novel ecosystems might exist in the future given that we’ve totally changed the physical characteristics of the landscape.

“Blue carbon is a way to sequester carbon specifically along coastal areas and remove it from the atmosphere.”

One of the species we find a lot on shoreline infrastructure is blue mussels. Those are not in the greatest abundance – the highest abundance would be barnacles – but they’re really good at filtering water. Coincidentally, for the last decade Boston has undertaken a widespread initiative to clean up the harbor’s water quality and is, as a result, seeing some amazing improvements. Adding to that, or even getting some sort of passive contribution to that would be if the mussel populations were to make a comeback here in Boston. Mussels, I believe, can filter around 5 L of water per mussel per hour, and so the amount of water clarity that can be improved by supporting mussel populations here is just one example of an ecosystem service that could be provided. They’re also referred to as blue carbon. Mussels, and any kind of carbon-based life form for that matter, will use carbon to make tissue and so they act as carbon sinks. Blue carbon is a way to sequester carbon specifically along coastal areas and remove it from the atmosphere.

So these species could potentially solve some of the pollution problems that Boston is trying to solve?

Yes! My ideas come up against and don’t necessarily always agree with traditional restoration practices, which seeks to identify the traditional state of the ecosystem and tries to restore it as much as possible. I think that in places that’s a very noble and worthwhile cause, but in urban areas I think the physical and social reality is that we’re not likely to go back to any kind of “natural state.”

“Given that we have grey infrastructure, how do we create meaningful green?”

We’re seeing this trend toward urbanization here in the United States and so a question I like to ask, which comes from my committee member Steven, is: “Given that we have grey infrastructure, how do we create meaningful green?” And sometimes I think that comes from the practice of habitat enhancement. This is ultimately where I hope my research will lead: ameliorating conditions where possible to promote settlement and survival of target organisms in the ecological community. Alternatively, we would be seeking restoration, which I believe to be a much more difficult path. Restoration would mean using Boston’s former ecological state as a target and trying to approximate it somehow. But that’s just my opinion. There are plenty of other takes on that.

Applied to coral reefs, based on this idea of habitat enhancement, would you be more likely to advocate from something like concrete reef balls instead of investing time and resources into reverting the reef back to a natural state?

I think coral is an exception as a rare and precious commodity these days, but I can see where you would draw that comparison. There’s certainly a tradeoff between balancing the needs of humanity with the reality of protecting the ecosystem. I don’t think that they’re mutually exclusive. Ecosystems do confer tangible benefits to humanity. In cases where a lot of degradation has already occurred, it can be helpful to think about what the benefits are that we miss or that we want and figure out ways to design for them.

If that means going towards creating a novel ecosystem based on a novel landscape, habitat enhancement through infrastructure is a promising strategy because it’s not like the built environment will disappear. This is especially true when we’re talking about cities like New York or Boston or San Francisco. Those are here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future. Figuring out a way to balance healthy, functional ecosystems within these human-made landscapes is our biggest challenge.

Where are you now in your research?

We just went out in the field for the first time two months ago and so we’re still in the data collection phase, now looking at the effects of substrates on intertidal communities that form on these walls across the extent of the harbor. So there’s three waterways: the Chelsea, the Mystic, and Fort Point Channel in Boston. We’re hoping to get enough data so that we can correlate substrate type with community assemblage. We’re too early to tell at this point.

Where do you see the future utility of the data?

One of the things I’d like to do as a graduate student is interview people working in spaces related to my science. I always want my research to stay grounded in some sort of reality. Ideally, the groups I really like talking with are the coastal development and design firms and environmental justice non-profits. Those two communities are the ones I’ve interfaced with most, especially when developing this study and figuring out how the results can be used to inform tangible strategies within the broader context of development. One of the interesting things that comes out of almost every conversation with a planner, a developer or a designer is that they anticipate the negative effects of climate change, even if the policies aren’t there to enforce their decision-making on a project.

For example, the living shoreline project that’s happening at the Wynn Casino right now. I was visiting there a few weeks ago and they confirmed their understanding that it would be unwise not to take [climate change] into account when you’re designing a new building on the waterfront. At the top levels of our government we may not have much support, but in practice (when the rubber meets the road) people do have that understanding and are taking climate change into account even if its in an unofficial way. My ultimate goal is to work for a design firm as the person in charge of designing the shoreline interface of coastal projects. I can envision myself synthesizing the societal demands with physical and ecological conditions, to design opportunities to enhance ecosystem functionality and help developers recognize and encourage ecosystem health, rather than degrade it.

I hope that at the end of my PhD I will have that knowledge, that value to add to coastal projects. I think there is a lot of uncertainty, you know, there’s not like a playbook or specific design guidelines for implementing coastal infrastructure. However, there are new varieties of a living shorelines where you’re not necessarily using living elements, like vegetation patches, to create habitat, but rather making changes to the materiality or the texture of a surface – in this case, the actual seawall. I think that is a new and growing area of understanding and where I’m hoping to contribute through my research.

Cryan would like to thank her fellow committee members, Steven Scyphers, Jon Grabowski, Dan Adams and Rachel Gittman for their tireless dedication to the project.

- Emily Atkin is pissed off about climate change. Her new newsletter Heated says we all should be - October 1, 2019

- How to grow your brand as a photojournalist and commercial photographer - August 1, 2019

- Six digital skills all new journalists should consider learning and a road map to unlocking them - July 15, 2019