Using GIFs to tell a story of strife and street life in Lebanon

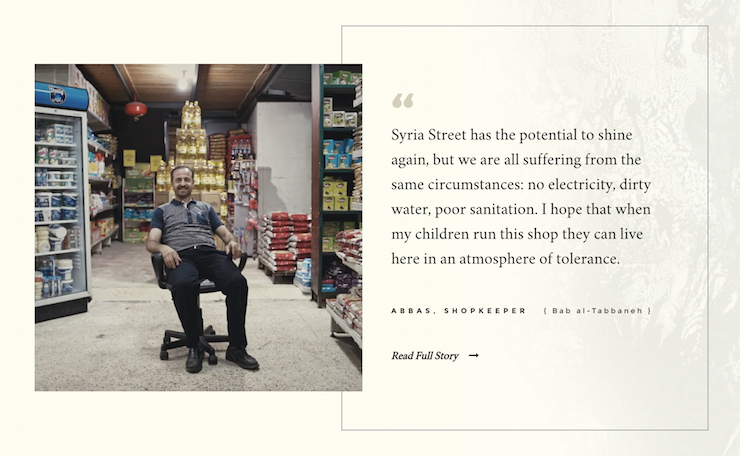

“A cup of coffee, a motorcycle, a pink bedroom with bullet holes. Meet the people of #SyriaStreet.” That’s how the International Committee of the Red Cross introduced its new interactive visual storytelling project featuring GIFS, “Syria Street,” this week.

GIFs are moving images, chosen as a storytelling tool by Syria Street’s creators to convey a sense of movement about – and perhaps a dose of empathy for – its subjects.

Syria Street, which can be read in English, French and Arabic, takes viewers the street of this name in Tripoli, Lebanon’s second largest city. The street is notorious in the city as the flashpoint where two warring neighborhoods converge. The project delves into the lives, homes and shops of people who have been fighting along this stretch of Tripoli for generations.

Syria Street, which can be read in English, French and Arabic, takes viewers the street of this name in Tripoli, Lebanon’s second largest city. The street is notorious in the city as the flashpoint where two warring neighborhoods converge. The project delves into the lives, homes and shops of people who have been fighting along this stretch of Tripoli for generations.

It’s a story of violence and resilience, says Brandon Tauszik, a filmmaker and creative director of Sprinkle Lab, a video production studio in Oakland, Calif., who produced the project. Tauszik sat down with Storybench to talk about how he started working with the ICRC, what drew him to Lebanon, and how he used cinematography and GIFs to tell an “age-old story of neighbor versus neighbor with complicated undercurrents.”

How did this project get started?

ICRC sent a cold email early last year, saying they wanted to up their storytelling game. They had seen Tapered Throne and wanted to create a similar transmedia experience. They work in 80 countries and they have access to stories from so many places. The question was where? They understood that they had this nest egg of work that they were doing but a lot of it wasn’t being told.

How did you choose Lebanon?

How did you choose Lebanon?

We went back and forth over different areas, some in Latin America, some in the Middle East. We ended up landing on this story in Lebanon. It’s this age-old story of neighbor versus neighbor with complicated undercurrents. I was drawn to the visual of this side versus that side. There are generations of conflict between the predominantly Sunni neighborhood of Bab el-Tebbaneh and the predominantly Alawite neighborhood of Jabal Mohsen. Both areas are no larger than a couple square miles each but, until recently, the fighting has been brutal and destabilizing for Lebanon.

Tell us about the conflict there.

Everyday life in Lebanon feels calm and yet on edge. It’s located between Israel and Syria which both possess hostilities. Their borders are porous and have obviously taken in a ton of refugees from Syria as well as from Palestine. But there’s a new ribbon of hope that I was able to capture in Tripoli. Up until 2015, clashes there would break out a few times a month. Eventually the Lebanese army moved in and has kept a continuous presence in the neighborhood. That’s keeping the peace right now. But it’s an uneasy peace. There are a lot of missing sons and fathers and retaliation to be had.

What were the challenges you faced in shooting this project?

The army controls everything there and were very strict about not showing any checkpoints or military presence. It’s not really a place where you can wander alone, so I had to work around that. Trying to explain through a translator what a GIF was and directing good movement from the subjects was a challenge.

Tell us about using GIFs to tell this story. Why?

I really enjoy the shots of everyday life and move the story along but I really feel that GIFs are useful in portraiture. They create an added layer of connection with the subject. I was tasked with synthesizing a very complex story for a Western audience and that audience quickly typecasts people from that area. With a film, everything is buttoned-up for the viewer; I wanted to take advantage of the GIF to connect with a human that has very little outwardly in common with you.

I really enjoy the shots of everyday life and move the story along but I really feel that GIFs are useful in portraiture. They create an added layer of connection with the subject. I was tasked with synthesizing a very complex story for a Western audience and that audience quickly typecasts people from that area. With a film, everything is buttoned-up for the viewer; I wanted to take advantage of the GIF to connect with a human that has very little outwardly in common with you.

Who worked on the project during and then after, to create the website?

[In Tripoli], it was just myself and Keenan [Newman], the cinematographer. Afterwards, it was like six months of post-production, creating the GIFs, deciding what stories to include, what to leave out, and how to structure the site. Finding some sort of narrative thread was a big challenge. Also, wanting to avoid my inherent biases as a Western person coming to a place where there’s been centuries of institutions in place that I’m not familiar with. It was really complicated. I was told a lot of ernest but conflicting opinions in Tripoi. I ended up embracing that, as causes of human conflict are inherently subjective and complex.

How did you put the site together and what challenges did you have?

My friend Javan runs Fifty & Fifty, a web shop in San Diego that mostly works with non-profits. They brought a lot to the table. They signed up for more than they thought they were. It was really a labor of love; It’s three languages, it has to be mobile-friendly, has a map, and more. As for challenges, the GIFs, for example, aren’t displayed as GIFs on the desktop version. They load as MP4s which raises the resolution.

We also had to keep Internet load times in mind. While ICRC’s social media would bring this story to Western audiences, we planned for this to be friendly for viewers with slower Internet connections.

Bryan Monzon, C.T.O. of Fifty & Fifty: The primary problem we had to solve building Syria Street was performance. On the surface, it looks like like a bunch of GIFs on a page. The problem is that GIFs are notoriously large in file size. Our lead developer on this project, Alex Zizzo, decided that on desktop views, he would use the built-in HTML5 video player. This allowed him to autoplay the videos and loop them. On average, using ffmpeg.org to compress videos (and keep preserve the quality) we were able to keep the video size on average around 196KB while on average the GIFs file size was 4248KB. (You can see the calculations here.) On mobile, not all browsers have the ability to autoplay and loop. In addition, inline videos often automatically take over the full screen when played. In order to to get around this, we used the larger sized GIFs but loaded them asynchronously. Outside of this particular challenge, everything written is custom Javascript and SCSS compiled with Gulp. The compression software used was FFMPEG.

Tell us about working with an organization like ICRC. Did they know how much work this would be?

Getting traditional organizations to engage in new forms of storytelling online can be tough, but ICRC was totally down to go all the way with this. It was a lot of work but we’re all happy with the end result.

This post has been updated to include comments from Bryan Monzon of Fifty & Fifty and to clarify the conflict in Lebanon. Tauszik also amended his comments about working with ICRC.