Good Luck Soup, a web documentary about Japanese internment during World War II

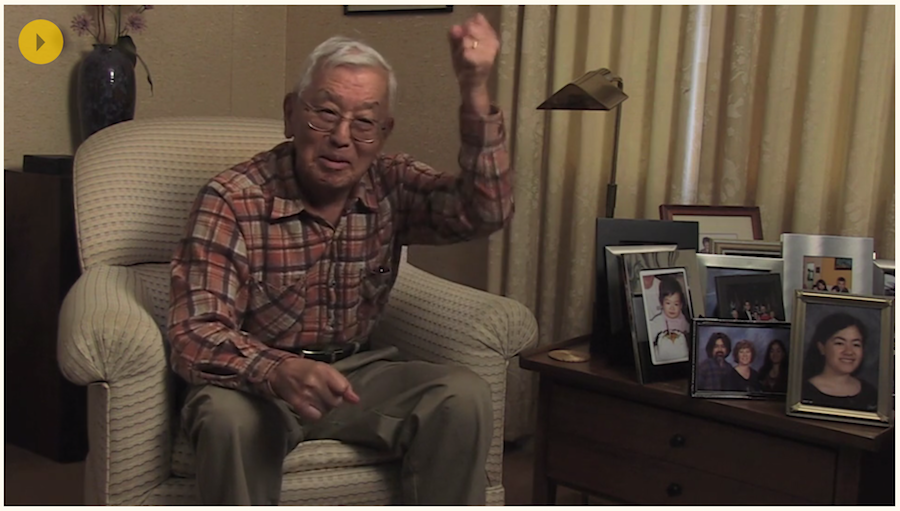

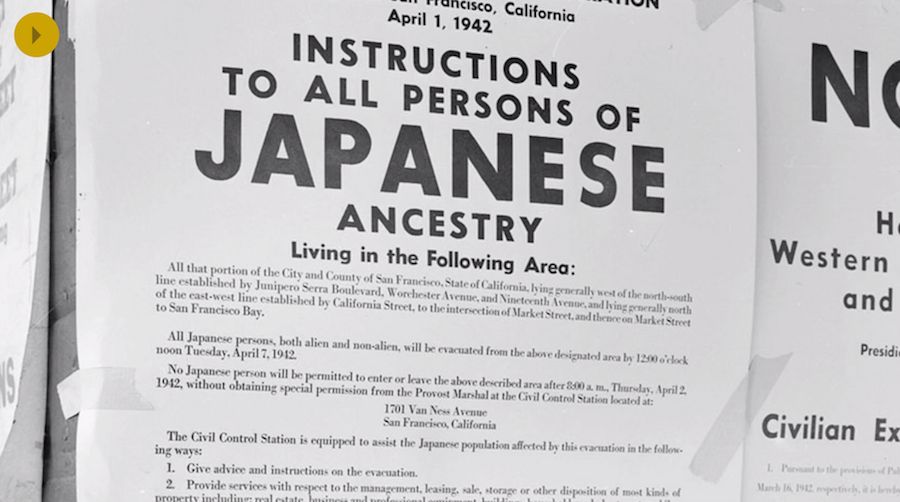

Among the 140,000 Americans and Canadians of Japanese descent forcibly evacuated from their homes into internment camps during World War II was the family of Matthew Hashiguchi. His new web documentary tells the larger story of his own family’s ordeal.

He named the film Good Luck Soup, after a traditional soup made with mochi, vegetables and seafood served on the Japanese new year to ensure prosperity and good fortune. The webdoc explores what happened to those prisoners before and after their internment. The feature-length film version of the documentary will be out in 2016. Storybench spoke with Hashiguchi, an assistant professor of multimedia film and production at Georgia Southern University, about the project.

How did the idea for this story come about?

It’s a personal story. This project initially began as a traditional documentary film that focused on my family’s experiences as Japanese Americans in the Midwest after WWII. My family was incarcerated during the War, and while the Japanese American internment story has been well documented (though not properly discussed) I believe the post-WWII story of Japanese Americans has never been revealed. So, I wanted to update the story and tell what happened after all those people left the internment camps. I wanted to tell both the positives and negatives.

While I continued to work on the documentary film about my family, I discovered many unique stories on the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience that didn’t fit within the single narrative of my family. So I created the interactive web experience for people like myself and family members to share their own stories and experiences as Japanese Americans or Japanese Canadians.

Where did you find the data, sources?

This project relies heavily upon oral histories rather than data. So, we needed interview subjects. Our approach has been to conduct “interview gathering sessions” in select cities where we interview, photograph and document stories with various individuals. Fortunately, finding subjects to interview hasn’t been too difficult since I’m part of the Japanese American communities in Ohio and Boston. It was just a matter of asking.

In addition to in-person interviews, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @MatthewHash”]this project was designed with the goal of gathering content through online submissions.[/inlinetweet] So far, many stories have come from people throughout North America that I’ve met and connected with online. They were able to share their personal experiences, stories and photographs by sending them to me directly or uploading them through the submission form on our website.

As the project progresses, story gathering will likely be an ongoing effort that will take many forms. We’ll continue to receive stories through online submissions and have already planned additional interview gathering sessions in cities like Philadelphia, Atlanta and Savannah.

How did you set up interviews and track down historical footage?

Most of the photographs that you view on the Good Luck Soup website were shared, uploaded or provided by the interview subjects themselves. So, they’re personal, family photographs that were gathered and documented during our interview sessions or through our online submission form.

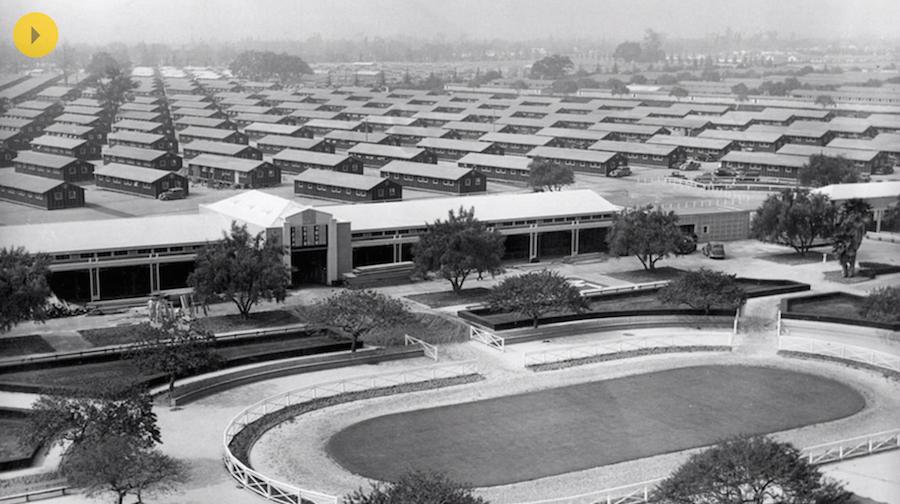

The historical footage and photographs used were available, royalty free, through the National Archives. I’d say a majority of the historical footage comes from WWII propaganda films. Photographers Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange also made much of their work from the internment camps available to the public and for educational purposes, which is certainly what we’re doing.

There’s been a lot of sifting, too. A few times I’ve been given boxes of old photographs that haven’t been touched in years and I’ve enjoyed going through all of those family moments. The living room floor has become a second office.

Please explain your process developing the website

We spent about four to five months planning the concept of Good Luck Soup website before anything was designed, coded or produced. It was a slow process but there were specific goals that we wanted to hit and we wanted to make sure that it was planned correctly.

Here’s what we focused on:

1) Simplicity: We wanted our audience to focus on story and not the technology.

2) Internet consumption: We wanted to cater the experience towards online consumption and a web-connected audience. This meant short, bite sized stories that could be experienced in under five or six minutes, while still offering the ability to discover more if one desired.

3) Closure: We wanted to ensure that the viewer wasn’t left in limbo and knew when the story ended.

4) A narrative. We wanted to provide a story structure and idea, while still providing freedom and interactivity.

5) Community involvement. We wanted the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian communities to shape this story through online submissions.

6) Accessibility: We wanted to ensure that it be accessible through desktop computers, tablets and mobile devices.

I have to admit that out of all my teammates, I was probably the least critical of the demos, prototypes and versions of the website. Russell Goldenberg was our web coder and designer, and Emily Ferrier and Billy Wirasnik worked with me on story development. I really trusted Russell’s ability and vision for the feel, look and experience of the website. I knew the decisions that he would making were coming from a good place of judgement. So, I trusted his choices as an artist and wanted him to run with it. Emily and Billy were much more critical and detailed with the website. They really honed in on specific parts of the interactive documentary that I probably overlooked. I think I was thinking in broad strokes whereas the others were paying more attention to detail and fine strokes.

Once Russell had a solid prototype, Billy, Emily and I went out and documented a number of stories and interviews to place into the website. It was important that it be loaded with material prior to launch.

Any interesting challenges? What didn’t work and what’s on your wishlist to fix?

Initially, I was mostly concerned with the quantity of content and stories that we’d be able to gather. The Japanese American Internment Camps affected over 120,000 individuals and the Japanese Canadian Internment Camps had some 20,000 victims. So we’re seeking stories from those individuals and their family members. The number of people who can share a story is literally in the hundreds of thousands, if not millions. But, now I’m much more concerned with quality. I’d rather have 100 good stories than 100,000 mediocre ones.

It’s also been hard finding early-immigration stories. We’ve been able to find many stories from post-War or WWII, but we’re also looking for experiences and stories from before WWII and the early 1900s. Those have been hard to find because many people just don’t recall those stories or don’t know.

It’s also been hard finding stories from the younger generations of Japanese Americans/Canadians… the 4th and 5th generations (Yonsei and Gosei). I’m not sure why exactly, but I think it’s because many are drifting from the Japanese American/Canadian identity and don’t have much to say about it. They’re more American than Japanese American. But, that is part of the story. We want those.

Another challenge is conducting interviews and information gathering sessions. Interviewing is a hard, exhausting task and very time consuming. Each interview that we’ve conducted yields about an hour-long audio clip that can contain 4-8 individual stories. But editing, sorting and compiling those stories is extremely taxing.

What should documentary students and newsrooms keep in mind when building this kind of a project?

We need to think about the technology itself and its impact upon the story and the audience. Are people interested in an interactive project because it’s a worthy story or because it’s being funneled through new technology? And if viewers are clicking through an interactive project, are they paying attention to the story or to the interface? When I made this project, I did so with the intention of educating an audience about the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience. Our goal was about the story, not the medium. So, if you’re going to make an interactive project, make sure your reason(s) for making it interactive or with new media are justified and don’t take away from the story.

Where can we go for more of you work? Can you give us a little bit about your background/experience?

The second part of Good Luck Soup, our feature film, will be out in 2016, so hopefully everyone will have the ability to see the film if they like the interactive documentary. The New York Times just published a documentary on labor strikes in New England that I shot for them and my website also contains a good amount of my work.

I recently moved to Georgia for a job at Georgia Southern University where I’m an Assistant Professor of Multimedia Film and Production and have just begun a new documentary on the experience of being undocumented and Asian in the South. I’m guessing much of my new work will focus on this strange place that is the South. I’m from Ohio.