The power of play: Why journalists should warm up to newsgames

For many newsrooms, it’s open season for games. More and more journalists and game designers are coming together to create interactive stories that use “play” to engage readers in powerful ways, offering them the chance to explore, experiment and learn with news.

“The power of games is the power of play,” says Lindsay Grace, an associate professor at American University and founding director of the American University Game Lab and Studio. “Play itself is the human animal’s way of exploration.”

Games are constructed around play, exploration and interactivity. Those are powerful tools for engaging an audience and getting people to not only read stories but insert themselves into them. Outlets like ProPublica, The Washington Post and The New York Times are starting to recognize that the way both video games and news succeed is remarkably similar: by engaging audiences.

But it’s been a long journey to get to this point. Every new form of play in journalism – from crossword puzzles to the newsgames of the 2000s – has been met with a large dose of skepticism. It’s taken a long time for journalists to embrace the idea of “play” in their work. The news industry, after all, is defined largely by its adherence to a grounded the written word. For the most part the misperception that “play” involves the audience having fun with otherwise serious stories is still present in many media outlets. In our digital age, journalists need to be willing to use every tool at their disposal in order to tell stories and engage audiences. Moving forward, games need to be part of that toolset.

Larry Dailey, chair of Media Technology at the University of Nevada Reno’s Reynolds School of Journalism, for example, is taking steps to combine journalism and game design. By bringing together students from different disciplines and urging journalists to experiment and play, Dailey hopes that games will become a regular part of journalism.

For Dailey the question of whether journalists should be using game design is irrelevant. “It’s like saying ‘should journalists be using writing or photography?’” says Dailey.

But getting journalists to learn how to tell stories with games is a challenge, partly because their storytelling potential is so new. Dailey’s interdisciplinary student projects – ranging from a virtual baggage scanner to a virtual cafeteria tray that counts the calories at Reno’s dining halls – are as much about educating journalists as they are about educating game designers. It’s about getting people to play and experiment with knowledge. That may lead to new insights.

“Because they have different knowledge bases they’re exponentially more likely to innovate,” says Dailey. Collaboration and getting students to “speak each other’s languages,” as Dailey puts it, is a great way to craft compelling games and stories.

However, a university setting is very different from a newsroom. Dailey, who has worked on MSNBC’s multimedia team, admits that time constraints and editorial pressures can often result in lackluster content. Play testing, a regular and time-consuming part of the game design process, is foreign to most editors. But for game development, it’s incredibly necessary. Oftentimes editors want a game that can be developed in a day or a week “and that game is going to suck,” Dailey says. “If you’re going to [design games], know up front how you want people to feel and learn.”

Rapid game development in newsrooms

There’s an expectation that games will follow the same rapid turnaround time that most new stories do, a consequence of how much time and money these projects can cost. But Grace, who started the American University Game Lab and Studio three years ago, approaches time constraints as just another challenge.

“We can make games at the pace of news,” Grace says. “The problem is expectations.” Few news organizations can support the structure necessary to build a game on the scale of a Call of Duty or Grand Theft Auto. Instead, according to Grace, newsrooms that want to make games at a fast clip should think about smaller games like one-panel comics. A low word-count with maximum impact.

But like Dailey, Grace admits that there needs to be a cultural shift in terms of how media outlets view games. Grace, whose games have received awards from the Games for Change Festival and Meaningful Play, says that a higher tolerance for risk is necessary to really push games in journalism forward. “We need to start letting people know its ok to play because it’s part of our creative process,” says Grace.

Experimentation can often mean failure, but that’s part of playing and learning. Dailey teaches his students the same lesson. There needs to be “space for failure and play,” he says.

Defying death at the Post

Although the spirit of play hasn’t fully made its way from game design to journalism, some media outlets have produced games that deftly combine good reporting, clean writing and playful game design.

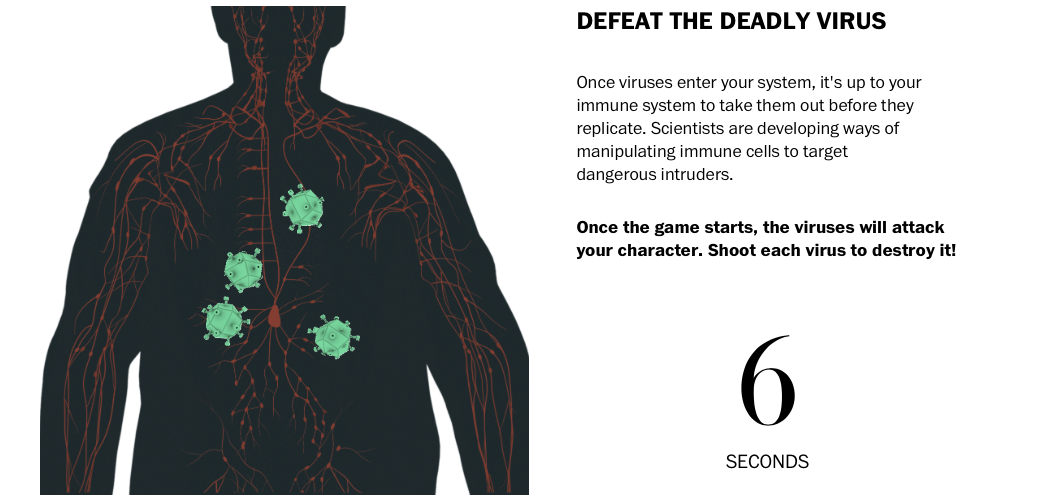

One of the more notable examples was The Washington Post’s 7 Ways to Defy Death. Published in April 2015, Sohail Al-Jamea, Patterson Clark and Shelly Tan used seven short, simple mini-games – such as aiming one’s mouse to “shoot” a virus or spraying skin cells on a third degree burn within a certain time limit – to teach readers about new technologies being developed to extend human life. (Storybench interviewed Tan when the game was released.)

For Tan, a graphics editor at The Washington Post and a gamer, this was an exciting and challenging opportunity. It was one of her first projects at the paper and it was different from most other stories she had worked on. Early conversations about the story always came back to the same thing. “We realized that as we were discussing it, we kept on coming back to the same idea: incorporating that kind of sci fi whimsy into the project. The idea was to make it more playful,” Tan says.

In that way, a game was the perfect medium for the story.

From the initial decision to create a game for each piece of technology in the story, Tan, Al-Jamea and Clark worked hard to balance the playful tone of the games with the scientific facts of the story. “While each mini-game was playful, the science behind each wasn’t,” says Tan. “We didn’t want our design to overwhelm the writing or story.”

At the same time, the team had to make sure that there were as few barriers to entry as possible. “Our usual audience isn’t used to game design, so every mini-game had a difficulty level we didn’t want to overreach,” Tan says.

Unlike most print or video stories, the team at The Washington Post had to learn how to leverage both the form and function of their story. It proved to be a valuable lesson for Tan. The project proved to her that both game design and reporting have to engage the audience in a meaningful way. Part of that means learning what stories work best as games.

“Video game design is not a fix all for your story,” she says. “It’s about creating a way to better showcase your story.”

ProPublica’s HeartSaver game

And it’s not just The Washington Post that’s leveraging game design in order to tell the best stories. At ProPublica, deputy news applications editor Sisi Wei is learning many of the same lessons with her own games related projects.

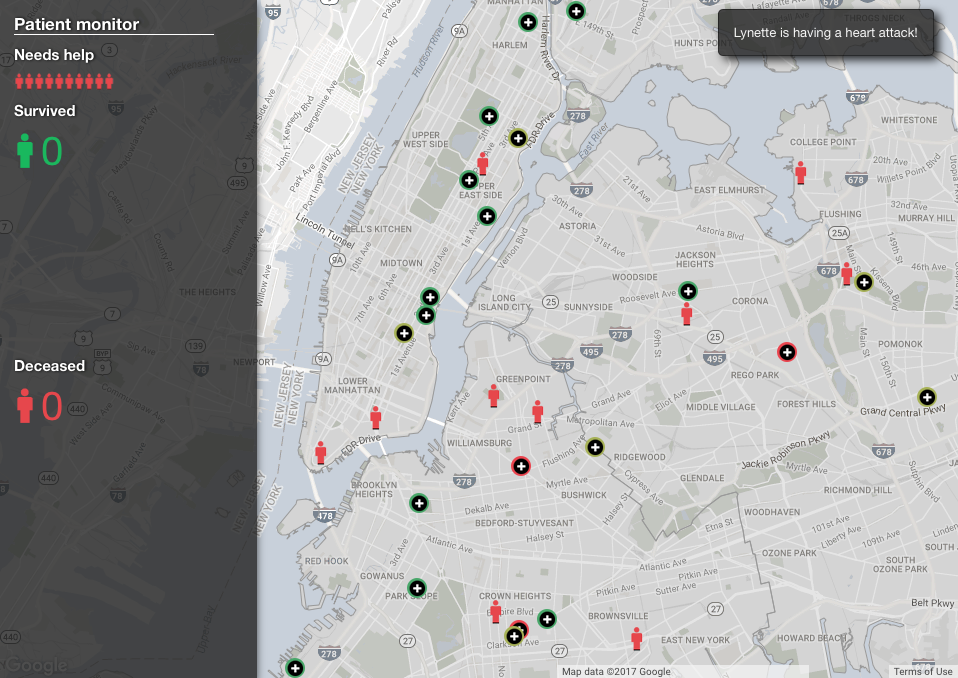

In 2013, along with fellow news application editor Al Shaw and senior engagement editor Amanda Zamora, Wei built HeartSaver, an experimental news game, as part of the GEN Editors’ Lab Hackathon. The game used Google transit data and data from specific New York City hospitals to task players with saving as many heart attack victims as possible by taking them to the best emergency room in as little time as possible.

“As journalists have game-based skills in the newsroom…it’s really about trying to identify stories that could really benefit from a games like approach,” Wei says. This particular story dealt with a lot of complex systems and, as Wei explains, “Games are inherently good at helping people break down complex systems.”

Much like 7 Ways to Defy Death, the heart attacks story worked best as a game. By forcing players to choose between the best hospitals and the time it would take to get the patient there, the game put people into the mindset of an emergency responder. And the project leveraged one of the best things about games – interactivity – in order to keep readers engaged.

Cultivating gaming culture in the newsroom

But Wei admits that the reason outlets like ProPublica, The New York Times and The Washington Post can make these kinds of stories is a matter of infrastructure.

“The departments that really make these kinds of things already make interactive graphics,” Wei says. “There’s not much variability in terms of how much time those take.”

But that shouldn’t discourage other outlets or journalists from making games. Wei says that games don’t need to be complicated or have a lot of graphics to work well. Free platforms like Twine, which let people make text-based games with little to no coding knowledge, can lower the barrier to game development.

Many journalists and readers are still learning how powerful games are as a storytelling tool. The more they learn how games can use interactivity and play to help tell the intimate, powerful stories that journalism excels at, the more potential there will be in combining the two. Game design is an extension of the reporting process. At the heart of any good story –including games – is good reporting and good writing.

“Good reporting in any form interacts with the audience in some way,” Tan says. “Good game design enhances good journalism.”

For more on newsgames, see Storybench’s “Newsroom: Game On” from April, 2015.