Visualizing Uncertainty in the Time of COVID-19: New York University’s Enrico Bertini on the role of uncertainty

Editor’s note: This is the third of three stories Storybench is publishing about the recent “Visualizing Uncertainty” conference at Northeastern University

An ongoing issue journalists and graphic designers face as the pandemic drags on is dealing with their own uncertainties about uncertainty. It’s something Enrico Bertini, an associate professor of computer science and engineering at the New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering, grapples with as he finds ways to understand visualizations of uncertainty surrounding COVID-19.

Joined by two other experts, Josh Holder, graphics editor at the New York Times, and Chiqui Esteban, graphics director at The Washington Post, Bertini spoke to Northeastern students about the importance of uncertainty at the Visualizing Uncertainty panel discussion on Oct. 14.

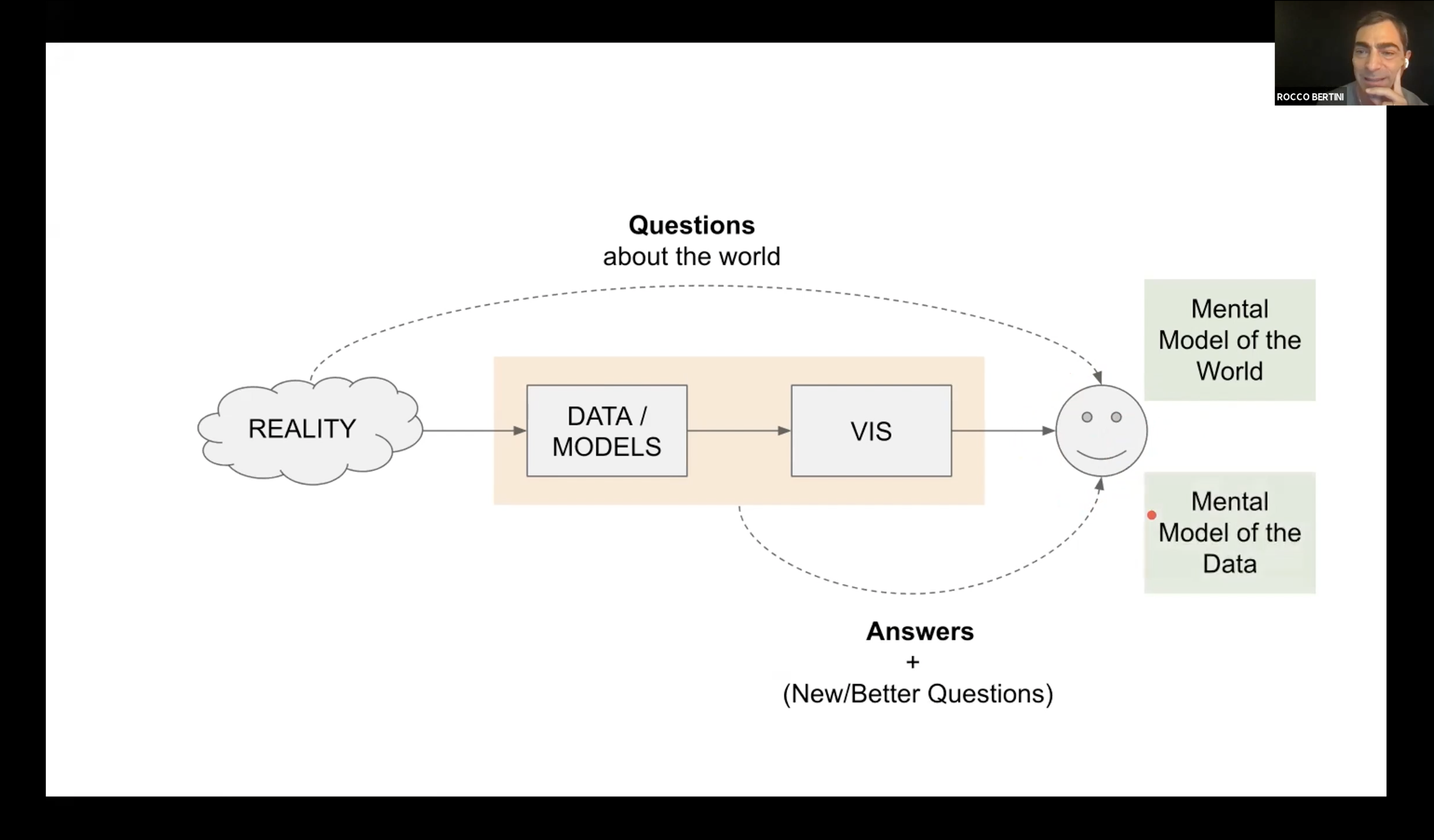

Bertini discussed the complicated relationship between reality and the preconceptions readers hold.

“We have some reality in the world, right, and the idea is that we try to capture elements of this reality with data and sometimes with statistical models on top of this data,” Bertini said.

“Then we take the data in these models, and we map them to some visual representation. Then this visual representation is presented to someone. This person typically has questions that are related to what happens in the world. In the most ideal scenario, you come up with answers to these questions.”

The primary issue, as Bertini identified it, is that these preconceptions often do not match what the data shows, so readers do not trust the data visualizations.

“Readers have what we call a mental model of the world, so in their head they have some ideas about how the world works,” Bertini said.

“They also have a mental model, even if it’s very rough, of what the data represents, and I think we too rarely talk about this. Data and models are a very coarse representation of reality and very often there is a mismatch between what we think the reality is and what we think is represented in the data. I think COVID-19 is such a perfect example of this.”

Bertini gave several examples of COVID-19 uncertainty issues, such as how the data sets we have do not necessarily tell us the information we would like to know. “We really want to know something that is in the world. But data, most of the time, have a very partial and skewed story of the reality that we would like to know,” Bertini said.

Delving deeper into exactly where uncertainties come from, Bertini turned to “gold standards” in science. Ideally, all scientists who perform tests and experiments using these standards would get the same results, but this is rarely the case, he said.

“You can almost always find studies that have different outcomes, even with the gold standard that is randomized control trials,” Bertini said. “For instance, some time ago, I wanted to understand whether meat is good or bad. Good luck with that. If you try, you find papers that say that it’s good and papers that say it’s bad.”

One of the questions Bertini continues to ponder is whether less certainty or less uncertainty is the answer. “I think that our intuition, when we talk about uncertainty, is that ideally we would like to have less uncertainty, but what I’ve tried to argue for is we want people to be less certain if things are not certain and I think that’s a really, really big problem,” he said.

Bertini’s personal stance on uncertainty rests within media’s inability or unwillingness to communicate it effectively. Among the reasons for this, he argued, is that media do not have the right techniques to do this, media do not try to allow people to think with uncertainty and uncertainty does not sell.

“I see a few foundational problems there,” Bertini said.

“First, humans really don’t like uncertainty, so anxiety comes from uncertainty and we don’t like to be anxious about things; we really like to be certain. Humans like to think dichotomously; we don’t really like gray areas. We want something to be either true or not true, but in most situations, things are not true or untrue. We also really love to think with emotions.”

Taking a quote from Northwestern computer scientist Jessica Hullman’s study, Why Authors Don’t Visualize Uncertainty, Bertini said, “The premise that most people have in the industry is that uncertainty omission is a norm. So, for instance, (when) interviewing people we have, in scientific communication for the public, the general consensus has been ‘don’t quantify your uncertainty.’”

As he ended his discussion, Bertini clarified that he thinks we do not need to cast doubt on everything, and there are some things that are absolutely certain.

“People are not ready to think deeply—there’s a huge data literacy problem, and this is where I’m super conflicted,” he explained. “I have very real uncertainty about how to think about uncertainty.”

- Visualizing Uncertainty in the Time of COVID-19: New York University’s Enrico Bertini on the role of uncertainty - December 14, 2021

- Visualizing Uncertainty in the Time of COVID-19: The New York Times’ Josh Holder on leading with questions when demonstrating uncertainty - November 17, 2021

- Visualizing Uncertainty in the Time of COVID-19: The Washington Post’s Chiqui Esteban on the Power of Words - November 8, 2021