Behind the scenes of the alt-right with The New Yorker’s Andrew Marantz

Originally published at the Northeastern University Political Review.

Thinkpieces on Donald Trump’s election and its underlying forces are like hard liquor. On November 8, 2016, as Trump’s victory shifted from implausible to unlikely to possible to probable to inevitable, Twitter responded in real time. It doesn’t take many words or much thought to tweet, so the takes were as close to instant as possible and, broadly speaking, not particularly illuminating or palatable. The liquor wasn’t aging at all.

A few hours later, the fully-fleshed articles started arriving. Many of them boasted coherent arguments supported by specific electoral results. This was slightly-aged liquor—still hard to stomach, but some effort went into making it and people begrudgingly consumed it in order to cope.

Then, as the calendar rolled into 2017, the books started hitting shelves. Anyone who reads a book instead of an article is declaring their attention span, and is more likely to absorb longer, in-depth interviews and extensive research backing up a coherent argument. This was aged liquor, a refined version of events, one that cost more money but ultimately stood a better chance of giving fulfillment.

Andrew Marantz’s book, then, was aged for several years in a fine oak barrel. Marantz, who has contributed to The New Yorker since 2011 and is now a staff writer there, has reported on the alt-right for several years, shadowing and interviewing movement leaders and trying to understand their methods and influence. He published the fruits of his reporting across numerous New Yorker articles.

But it all came together in Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation, released in October 2019. The book details Marantz’s reporting as he embeds himself in a far-right media world still pleasantly intoxicated from Trump’s election win, but always looking for the next political fight. Marantz’s first-person, opinionated writing allows the reader to experience the author’s emotional and informational journey.

“This is a book about how the unthinkable becomes thinkable,” he writes, “…Trump was intolerable in a hundred different ways; but tolerance is a social norm, not a law of nature, and social norms can and do change.” He also notes the stakes of internet influence and its inseparability from everything else: “To change how we talk is to change who we are. More and more every day, how we talk is a function of how we talk on the internet.”

The Northeastern University Political Review spoke with Marantz about his reporting, the lessons he learned, and how we can navigate a fast-changing, interconnected political sphere. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

You said that you “did not succumb to the misconception that a journalist must present both sides of every story, or that all interview subjects are owed equal sympathy.” You also wrote that “sometimes, even for a journalist, there is no such thing as not picking a side” and that traditional reporters “could be evenhanded, or they could tell the truth” on alt-right issues, but not both. If total journalistic neutrality or objectivity is impossible or unworkable, what principles should replace it?

I just finished reading this book The View from Somewhere, which is a diagnosis of where we are on the question of journalistic objectivity. That book does a kind of taxonomy of terms of objectivity as opposed to neutrality as opposed to lack of bias and draws distinctions between them, which I think are useful in that academic context.

In everyday parlance all those things get conflated, which is understandable. And frankly, there’s a good and bad sense in which we can allow these things to be declared dead. There’s a healthy sense of allowing these things to be seen as obsolete, which is declaring your priors, not being willingly obfuscatory in your aims. There’s obviously a more dangerous sense, which we’re more immediately familiar with, which is just making shit up or deciding what’s true in a kind of autocratic way.

Obviously, I’m for the former and not the latter, but a lot of it is case-dependent. I try to get into specifics a little bit. Obviously if you’re talking about preferences on how to mark up a specific treaty or the fine points of trade policy or something, as a journalist you’re not doing your readers a favor by putting a thumb on the scale.

Even here you need to get into finer distinctions about what kind of journalism you’re talking about. There’s newspaper journalism, more magazine-y journalism which has always been more filtered through the writer’s opinion which readers have come to know and expect from a certain kind of magazine piece. There’s documentary filmmaking.

So you have a different compact with your audience depending on which type of journalism you’re doing, but let’s take the most straight-ahead, standard, traditional form of journalism. Even in that form, part of the problem in recent years has been people trying to graph the version of neutrality you would use if you were talking about some obscure trade policy onto basic questions of value like “How should we feel about white nationalism?” And it just doesn’t track.

Why did you detail your reporting and make yourself a character in the story?

Partly because of decisions like this. There’s an understandable reticence—which I share and which I think other people have even more—to not make yourself the story, to not be too solipsistic about it. We’ve all read stuff where you feel like, “I don’t really care what the author ate for breakfast that day; I just want to get to the point.” So I wanted to avoid that.

But it felt like it would be, if not dishonest, then just a little bit willfully incomplete to ignore the fact that in a book about new forms of media production, I’m doing a certain kind of media production just through the act of being there. There’s an observer effect in all kinds of reporting, but in this case it was particularly stark.

All the people that I’m writing about think of themselves as media producers, announce themselves as media producers, compare notes with me about the way that I’m producing media about the media that they’re producing. So to pretend that my part of that equation wasn’t happening would have warped the story I was telling more than putting it in would. So it was sort of a tradeoff. I thought it was worth the distraction of putting myself in because it would have been even more distorting to leave myself out.

While you researched, did you face backlash from the alt-right community?

Oh yeah, constantly. I could have pretended that I don’t have any ill will toward them, but they were constantly declaring their ill will toward me.

It would have been a mistake to say, “These guys are making memes on Reddit where my face is in a gas chamber, so I’m going to do the same thing to them.” Obviously I’m not going to stoop to their level, but their antagonism toward what I represent is part of the story.

Sometimes it was just so general that it was hard to take seriously. Sometimes it was just, “Oh, you’re a media elite cuck blah blah blah.” I didn’t take any of it personally, but that stuff would have been impossible to take personally because it literally had nothing to do with me.

Then there was stuff where it was either my name or my face or whatever. Trolling is always better when it’s personally tailored. But again, it never really was that deep or that well-informed.

A lot of these people have a sense that they’re playing a game that has public and private faces, and don’t really feel much of a need to have those two things cohere. You see this all the way up to Trump, where he’ll blast the fake news all day and then literally call Maggie Haberman or Bob Costa on the phone and nobody seems to really give a shit. These guys are playing the same game.

What is the advantage of spreading alt-right talking points through memes? How does it affect the murky distinction between actual hatred and trolling, jokes, or provocation?

It’s always hard to tell which is which, and that’s partly because it’s always a little bit from every column. There aren’t sharp distinctions in these things. The advantage for people—and again, these don’t have to be mutually exclusive—is money, fame, attention, advancing an ideological agenda, or all of the above. And there are all kinds of other related things and sub-categories. But we’ve built an attention economy that is designed to reward the most titillating or outrageous content with the most immediate attention and people are built to crave attention.

Is the attention economy inherent in social media or our content consumption habits? Is there a way around it?

There’s always been an attention economy, but social media transformed it in the same way that there have always been people who wanted to consume calories, but it’s modified by how many food deserts there are and how many McDonalds there are on every corner.

I sometimes see pundits and people trying to set up dichotomies between “Oh, twas ever thus” or “This is totally novel,” but anyone who thinks about it for a minute knows that neither of those is really true. There have always been liars, there has always been propaganda, there has always been a human desperation for attention, but by pouring old wine into new bottles you can completely transform everything about how people behave.

How can people be intelligent skeptics online? How can they make informing themselves less overwhelming and more manageable?

I worry about this. I worry about people just retreating into the feeling of “Well, I’ll never know anything anyway so I’m just not going to try.” That’s the wrong approach.

There are the facile answers; you can try harder and spend more time and read more. That works, but not everybody has the time or inclination. There are long-term, systemic things that we as a polity can to do improve the informational health of our information systems.

On an individual level, you have to come to some reasoned conclusion about which sources you want to trust and put your trust in them. It’s funny, you hear this desperation coming from a lot of people these days, going, “I wish there were just some set of trained professionals I could turn to to tell me—on a daily or weekly basis—what is most important, rank it in order of what I should pay the most attention to, and give it to me in a reliable and straightforward way.” We already invented that, it’s just not really cool to like it anymore.

You said that “instead of imagining that we occupy a post-gatekeeper utopia,” we should “demand better, more thoughtful gatekeepers.” Who counts as a gatekeeper and what would more thoughtful gatekeepers do?

There are a lot of different gatekeepers at different levels, but the ones that I call in the book “the new gatekeepers” are the social media [megaliths].

There are still old gatekeepers. TV is still important, even print and pixel media are still, to some extent, important. Media is everything and tech is everything so it’s not just this or that main source. It’s also anything that can corral human energy into any kind of informational channel. Those could all be considered gatekeepers.

Another kind of flawed dichotomy that I see sometimes is people equating gatekeeper on one side and freedom from gatekeepers on the other with old vs. new or traditional vs. disruptive—with heavy air quotes around that—and these things don’t track perfectly onto one another. There are plenty of new disruptive things that are just as much gatekeepers in the way they function, if not more so, than the old. You don’t really have to look much further than the fact that a lot of the most august, traditional, legacy media brands have completely fallen apart or are actually defunct. You can’t be a powerful gatekeeper if you don’t exist.

So to me, all gatekeeper really means is an entity or person with the power to channel human attention in powerful ways that are outside of the control of any individual user. Social media companies and the people who control their algorithms absolutely fit that definition. The difference is that they’ve been in denial about that for about twelve of the sixteen years of their existence. Not only have they denied it, but we as a society have participated in that denial and glorified them as liberators when that has not been the case. Do I want to arrogate more power to these people? No, I don’t. But I want them to take responsibility for the power they already have.

Many alt-right media figures know how to get their messages from their outlets to FOX News to everywhere else, showing that despite their professed contempt for mainstream media, they recognize its influence. Should mainstream outlets change their approaches or practices to avoid being manipulated?

Definitely. Nobody should want to be manipulated. That could only be happening for one of two reasons: either they are unaware of it or they are aware of it but they don’t classify it as manipulation. They call it “being informed by new sources of information” or whatever.

You can’t just not take tips from anonymous sources or you wouldn’t get good tips. You can’t just not listen to stories from the periphery or you’re willfully blinding yourself. So obviously the principle can’t be “Don’t run stories that you heard from anonymous weirdos on Twitter” because anonymous weirdos on Twitter give you a lot of good information. You have to be skeptical, you have to be contextual.

There’s also a business model problem. You have legacy media companies that are barely solvent or, in many cases, insolvent, and they are desperately churning out as much content as they can and they need stories. They’re not going to be at their best when they’re acting out of desperation. I don’t blame individuals for getting duped sometimes. I think it happens to everyone. The question is “How much can you make it a priority to figure out a better way to do it?” And some of that starts with not running with a story unless you know exactly why you’re doing it.

Are there stereotypes about the alt-right and its ideology that you found were inaccurate or misleading?

When I came into it, it wasn’t even really settled what the alt-right was. It still isn’t really settled. But at the time it was very much in flux. There was a time when the Republican nominee for president was in that category. There was another time when it was just ten open Nazis in a field somewhere who fit that category.

The one main misperception—it’s hard to remember, I’m sure I held it for some time—but there wasn’t that much time between when I got interested in this stuff and when I started looking into it closely enough and interacting with people in it enough to be disabused of this. But the immediate misperception is, “Oh, these people are rubes, these people are idiots, they live in complete isolation, they don’t have access to education, all those things.” And those don’t really turn out to be true.

Obviously there are people in the movement who are idiots because the conclusions that they’re reaching are often monumentally wrong, so some of that might be due to lack of critical reflection. But a lot of times it’s not, “Oh, these people are too dumb to know that you shouldn’t be racist.” It’s a very calculated choice they’re making, and there’s a lot of high-IQ, really well-educated people in these movements, which makes it all the more pernicious.

You extensively discuss the difference between the alt-right and the alt-lite/New Right. Why is distinguishing the two important?

For the purposes of the project it was important to distinguish just so people knew what I was talking about. When you’re telling the story of these sub-groups and these people have intense rivalries and are trying to ban each other from getting into each other’s social functions, those rivalries aren’t going to make any sense unless you know that these distinctions are being drawn by these people. So for pure anthropological accuracy, I thought it was important.

But I also think it’s important to not lie about your subjects. We started out talking about how I don’t feel that I owe these people neutrality. I think it’s an easy leap to go from there to saying that you don’t owe them accuracy. And that’s a huge mistake.

I don’t like bigots and misogynists and anti-semites, but I’m not going to call someone a bigot or a misogynist or an anti-semite unless I have evidence for that. If somebody is the first two but not the last of the three, then I’m going to call them the first two but not the last. That’s a pretty big part of the distinction between the alt-lite and the alt-right. Some of them are anti-semitic, some are not. So I’m not going to call someone a Nazi if they’re not.

Now, sometimes people lie about what they are and you can’t just take them at their word, but you also can’t make stuff up.

If ignoring right-wing trolls and extremists makes us complacent and complicit, and responding amplifies their message and legitimizes their views, what should we do?

There’s no good answer. This is why I call it an ingenious trap, because it’s a trap. The long-term solution is to create social and discursive conditions that do not make it likely that people will publicly espouse these views or privately hold them. The long-term goal is to create a more just society where there aren’t bigoted, rampaging groups of anonymous trolls. Once they’re out there and they’re sincere and motivated enough that you can’t really put them back in the bottle just by magic, then there are no good solution at that point. There are a range of less-good solutions.

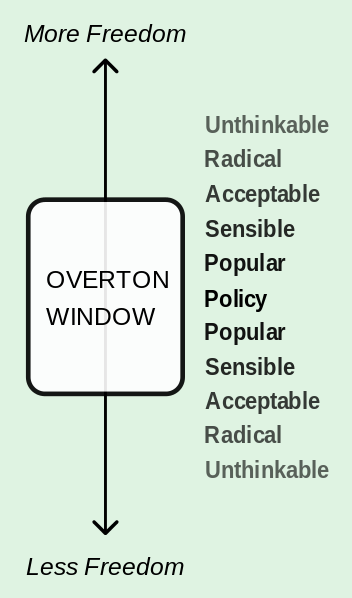

Many of your interviewees talked about intentionally moving the Overton window. Some of their online posts seemed to desensitize viewers over time until hatred became normalized and the intolerable became tolerable. Is there a way to combat this?

Depends on how we define it. To some extent, that’s just the definition of political activism. You want to move the boundaries of discourse; that’s what the National Review does, that’s what Jacobin does. This is just an extreme example. It’s not like advancing an activist agenda per se is a dangerous thing; it’s that there are ways to do it that are more honest and internally consistent and there are ways to do it that are more like guerrilla warfare.

What exactly is a “new moral vocabulary”?

What I meant was that naming and shaming racism doesn’t fix racism. Fixing racism fixes racism.

If your response to the new incentive structure of the twenty-first century attention economy is to win immediate plaudits and feel better about yourself and have a viral post by cancelling someone, you’re not getting out of the attention economy; you’re participating in it.

To get back to what I was saying about the trap that trolls set, I’m not therefore saying that all you’re ever left to do is studiously ignore these things or not comment on them or not express outrage about them. A lot of these things are outrageous and people should be outraged by them. I’m not saying that all you can do is be an ascetic and studiously self-censor and just ride it out for the next hundred years and hope that democracy saves itself. I’m saying it’s superficial.

If we want to create a world where it’s not a live option, it’s not a real, valid, or viable political strategy to be an open white supremacist or to deny the truth at every turn or to be a trickster, if we want to create a world where those things aren’t at all empowered, there’s a variety of ways we can do that. We can make those things seem boring, we can scorn them, we can mock them, we can fight them with reason, we can fight them with art. There’s a variety of approaches and they should all be taken up, but I don’t think we can be complacent enough to say, “We’ve discovered all the bad apples.” It’s not a bad apples kind of problem.

Doxing is a constant worry for prominent alt-right figures. Is it an acceptable response to their spreading of hatred or should we stop doing it?

It depends. This sort of gets down to a semantic discussion of what we mean by doxing.

There are people who are powerful and anonymous who don’t want to be named who—you could make a convincing argument—are powerful enough that it’s in the public interest to name them. If Stephen Miller was a pseudonym and nobody knew who he really was and a journalist found out who he was, there would be no question in my mind that that’s newsworthy information.

What I have doubts about is doxing low-level foot soldiers in the movement for the sake of feeling like you’ve done something. There are people who will say that it creates a deterrent effect and all this stuff. There are arguments on both sides, but it’s certainly not sufficient. If you’re going to engage in it you need to be honest with yourself that there are major drawbacks in addition to whatever benefits you think it might have.

Many of your sources speak in general terms about their perceived enemies: the left, academia, mainstream media, the establishment. How does this affect political conversation?

It’s important for any group, especially a group that purports to be a sort of insurgent, underground movement, to have enemies. Generally, from a propaganda perspective, you want to define your enemies as broadly as possible. And again, you don’t have to be an underground movement. You can be literally the president of the United States and you can still find great utility in naming an enemy. It’s a great advantage to not be constrained by coherence. You can name the press as your enemy and then spend literally all day talking to the press or engaging with the press. Then you can have it both ways.

The master of this was [Steve] Bannon, which is why when Trump fired him, his official presidential proclamation, which was just a catty string of insults, one of the main insults in there was “Sloppy Steve just sits around all day doing nothing but talking to the media.” That was true, but it was also pot calling the kettle black.

But it was Bannon who invented this popular notion that he was this renegade populist out there on his own who couldn’t get the attention or acclaim of media. He actually punched above his weight in terms of how much attention he got and, in some cases, still gets from the media. It’s really really helpful to have enemies. As you know from reading the book, conflict is attention.

You tell the story of Samantha, a young woman who went down a five-day internet rabbit hole, joined the alt-right, then found her way out. Why did you tell her story and what can we learn from it?

I had spent so long at that point with people who were movement leaders, or who purported to be, and I wanted the story of someone who was a run-of-the-mill convert. She ended up scaling the ladder to become kind of a leader within the movement, but the part of her story that I was initially most interested in was where she gets red-pilled [convinced that far-right ideology is correct].

It’s really hard to cut through the spin and the bullshit when you’re talking about full-time propagandists. I spent so many hours talking to so many dozens of people, but I didn’t have that many moments of feeling like somebody was candidly spilling their guts about what it was like because they were still in it. So to find somebody who was in the process of coming out of it, to watch her deprogramming herself in real time, was valuable.

One of the main things we can learn is that pretty much anyone is susceptible. She’s absolutely not stupid. She’s a thoughtful person. She just got really duped.

People think that gambling addicts don’t know that they’re losing money at the casino, but that’s just empirically not the case if you go ask them. So it’s really dangerous for us to think that the way to inoculate yourself against the worst ideas in modern history is to be a nice person and grow up in a diverse town and read books in school and be a good kid. Those things don’t inoculate you.

Again, this is why it’s just insane and naive to think that if we just go out there and find all the racists, we’ll be done beating racism. The problem with that ideology is that they don’t just go away because you’ve found all the people who are currently subscribing to the ideology. They can find new converts. Misogyny and white supremacy and fascism are pretty robust ideologies. They weren’t invented five years ago on the internet by some small, finite set of individuals.

So one thing that we can learn from the story of someone like Samantha is that we need to create a world where a smart but aimless and gullible person is exceedingly, exceedingly unlikely to fall prey to really bad ideas and I don’t think we’re there yet. And it doesn’t have to be just literal Nazism. There’s a whole array of bad ideas that people can fall prey to.

Can a network of people this size that operates mostly online have dog whistles?

Yes and no.

When it’s sophisticated it can be. There are times when they want to communicate more overtly with each other. There are times when even when you spend your entire life thinking in code you can kind of get “caught” saying what you really mean. But often you can.

I don’t think it’s just a simple one-to-one translation game, like, “Oh, you said this word but you actually meant that word.” That’s sometimes the case, but more often people might not be doing a conscious act of translation. They might not be saying, “Well, what I really want to say is that this country should be 100 percent white, what I’m going to translate it into is a rant about the globalists.” I don’t think it’s that conscious.

Most people who I would consider to be revanchist would not think of themselves that way. I don’t think that getting everyone to accept my labels for them or vice versa is going to fix the problem. So I don’t think it’s purely a question of hearing the symbols properly. It goes deeper than that.

To your point about whether the cat can stay in the bag, or the dog whistles can stay in the bag, I think these things always shift and get more sophisticated over time and respond to incentives. So if there’s a certain list of words that will make the AI bots and human moderators perk up on various social networks, people will learn not to say those words. So in that case, yeah, you can have a big movement that runs on dog whistles. There’s that whole Lee Atwater school of thought that the modern Republican party is a large group of people that learned to communicate through dog whistles. That’s Lee Atwater’s diagnosis, not mine.

The podcast was a 4chan board come to life, full of naughty words and obscure allusions and meta-ironic gas-chamber memes. The purpose of all the shitposting, beyond the usual trolling and triggering of the libs, seemed to be to desensitize the listener over time—to say the unsayable again and again, until grisly hatred came to seem like just another thing on the internet.

Your Facebook search found more “right-wing garbage” than “left-wing garbage.” How did you approach your content searches on Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, and other sites to ensure that you could draw accurate conclusions?

That’s why I phrased it as “what I found.” I don’t think anybody can know the entirety of Facebook content, not even Facebook. That was a particular moment in time when the exciting insurgence candidate happened to be a reactionary candidate and the establishment, milquetoast candidate happened to be a center-left candidate. That maybe would be different if it were another election where it was Mitt Romney against Jeremy Corbyn or something like that, I don’t know.

Some of this has to do with the thin language we have available to us. “Left” and “right” are only so useful as terms. If you have a two-party system and one party hearkens back to the days of yore which involved segregation and subjugation and all that stuff, and the other party is putatively wanting to move forward from that, it’s easier to gin up an immediate negative reaction or positive reaction or just incite any kind of physiological reaction from the largest number of people by referring to the former than to the latter.

What was the most appalling thing you read or heard while researching the book? What was the most encouraging thing?

I found a lot of things that were appalling. They’re all tied for most.

I just didn’t expect to go this far down the rabbit hole at first. I didn’t expect to be hanging out with literal neo-Nazis. I didn’t expect the spectacles like Charlottesville to be as overt as they were. Obviously there have always been neo-Nazi marches in America, but I didn’t expect things to be quite as on the nose as they got. All of that was pretty discouraging.

What I found encouraging is that there are lots of people like Samantha who, as much as it’s perplexing that they could find themselves sucked in by this stuff, they really have a powerful drive to get out. I’ve seen lots of other cases like this where people don’t have any immediate incentives to get out other than just hearing a voice within themselves that says, “This is fucked up, I need to leave.”

I don’t think that can be all down to individual agency and ingenuity. We have to create systems that encourage all people to move in the right direction. Knowledge is socially produced. It can’t just be leaving the onus on each individual to discover the truth for themselves.

I’m skeptical of notions of truth with a capital T to begin with. But I did find it encouraging that as much as I focus on the Overton window moving in scary directions, there’s nothing intrinsic to suggest that it can only move in that direction. Quite to the contrary. It can move in any direction that people push it more powerfully. It’s as simple as that.

Cover photo: The Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally. Anthony Crider via Flickr.

- Behind the scenes of the alt-right with The New Yorker’s Andrew Marantz - January 21, 2020