Breaking down “The Big Bang Theory,” Chinese censorship, and data journalism with Manyun Zou

Growing up in China, Manyun Zou spent many of her teenage years unwinding with episodes of the popular American sitcom “The Big Bang Theory.” Little did she know, her favorite pastime would lead to a powerful data story.

While streaming from Youku, a Chinese entertainment company, Zou began noticing inconsistent jump-cuts in the middle of sentences, jokes cut off abruptly, and bounces in audience laughter. As a data journalist, she had to wonder: what kind of content was being censored, and why?

By comparing the first 100 episodes of the Youku version of “The Big Bang Theory” with an uncensored streaming service’s version, Zou began piecing together exactly what made the cut. She categorized her finding into three distinct content types; sex tropes, LGBTQ+ language, and disrespect towards China.

Zou brought her questions to The Pudding, a digital publication that explains cultural ideas with visual essays and data. And while much of Zou’s story speaks for itself, the journalist is eager to help unpack everything behind the scenes: from her background in journalism to the laborious data collection process, the tricky design choices, and the sensitive nuances of the issue of censorship in her own country.

She let Storybench in on all of the details of “The Big [Censored] Theory,” for The Pudding.

What was your journalism education like?

I’m sure you know the journalism schools in America are more for practical skills. You have to go out and interview everyone. First year, I was like, “Oh I want to become a video journalist, because I don’t write English.” So I was like, “OK, I’m going out to shoot video, record and everything.” And I suck at it. I suck at doing all the machines. I always forgot to record, or I shoot and cut people’s heads out.

So, then I was like, “I don’t want to do that,” and took a class called computer-based reporting. And it’s kind of like data journalism 101. It was already my senior year, but I was like, “OK, I think it’s fun … I think I want to change my [focus].” So I actually only took three courses related to data journalism. After I finished a Python class, I said ‘Oh I am never going to touch this again.’ Because it is so hard.

How did you decide you wanted to pursue a career in data journalism? Were you able to apply some of the skills from your undergraduate degree to your job?

So after I graduate, I think I am going to become an interactive designer. I like front-end things like Javascript. So I got a few freelancing jobs in America. Then I applied for a job in this Chinese newsroom because I still want to be a reporter. I still want to be in the journalism business. They don’t have the head quota for the design side; they only have the quota for the data editor side.

So I said, “OK, I am going to take that.” I started reporting with data. That’s when I’m more into the field, because I tried to pitch as many ideas as possible because I want to dig into the field. The more data that I am using the more I realize I have to learn Python. The courses in my undergraduate kind of gave me a head start. But I think most of my skills I learned as a data journalist I picked up as I was actually reporting.

How did you get the idea for the Big Censored Theory data project?

So I had always been a fan of the Big Bang Theory. So that was my first American TV show I watched through high school. It’s a thing [with which] I started to learn English and learn American culture. I really like the show because I like sitcoms a lot.

So I was watching the show at the beginning of this year, on a Chinese website called Youku. I was watching the show, and I realized that there are some weird pause, and cuts, especially because “The Big Bang Theory” has the laughter they put in the background. Since I was a data journalist, I thought, “OK, this could be fun to see what is going on there.” I don’t want to be paranoid or crazy, so I just sit down, and I watch the show on Youku and the original side-by-side and just play [them] together, and see what has been cut.

How did you begin the data collection process, and when did you know this could become a published story?

I think I watched the first season, which is about 20 episodes. I went through the whole season, and I opened a spreadsheet and took notes about what had been cut — like what kind of lines are in there and how long has been cut. All this type of data. I put it all in a spreadsheet and said “OK, there definitely has been stuff that’s been cut and I can see the categories.”

So I categorized it. The sex trope content, any China related thing — OK, that’s interesting. That’s a very Pudding thing. I love Pudding articles. I think they love the kind of story that looks from a very tiny aspect of life but showcases a wide range of things. So I think “The Big Bang Theory” could be a thing to show how censorship influences everything in China.

Do you feel like, as a journalist, sometimes it can be difficult to dedicate a lot of time to research if you don’t even know if it becomes a story?

I think it really depends on how interesting it is to you. Like how much of a passion. So I really liked this project. So even though I needed to work in the daytime, I was spending my night time doing “The Big Bang Theory” [research]. I think it’s hard if I am not quite interested in the topic. That would be a pain in the ass. I think the research — it’s always better to do after work time.

How did you decide to organize the data and incorporate it into the website?

We were talking about how much data should be collected. Should I go through all eleven seasons or is the first season enough? So we had to talk about this, and I was like, “I want something to be a very eye-catching, very surprising database that shows wow there has been so many things that have been cut out.” And I don’t think the first season is enough. So we were talking about that and Rob the editor said “Oh, we can try the first 100 episodes because that would be a perfect number.”

I think the database was pretty good because we got five different colors to represent different categorizations. And we used the colors to coordinate with the videos or the image we used — the same color that was associated with the original categorization. So I think that’s [why] the reading is very smooth, like you could connect everything together and make sure that every categorization has some visual examples or text examples.

What was the most surprising part of your findings? And was there any area that you weren’t surprised by because you grew up in China and expected that sort of censorship?

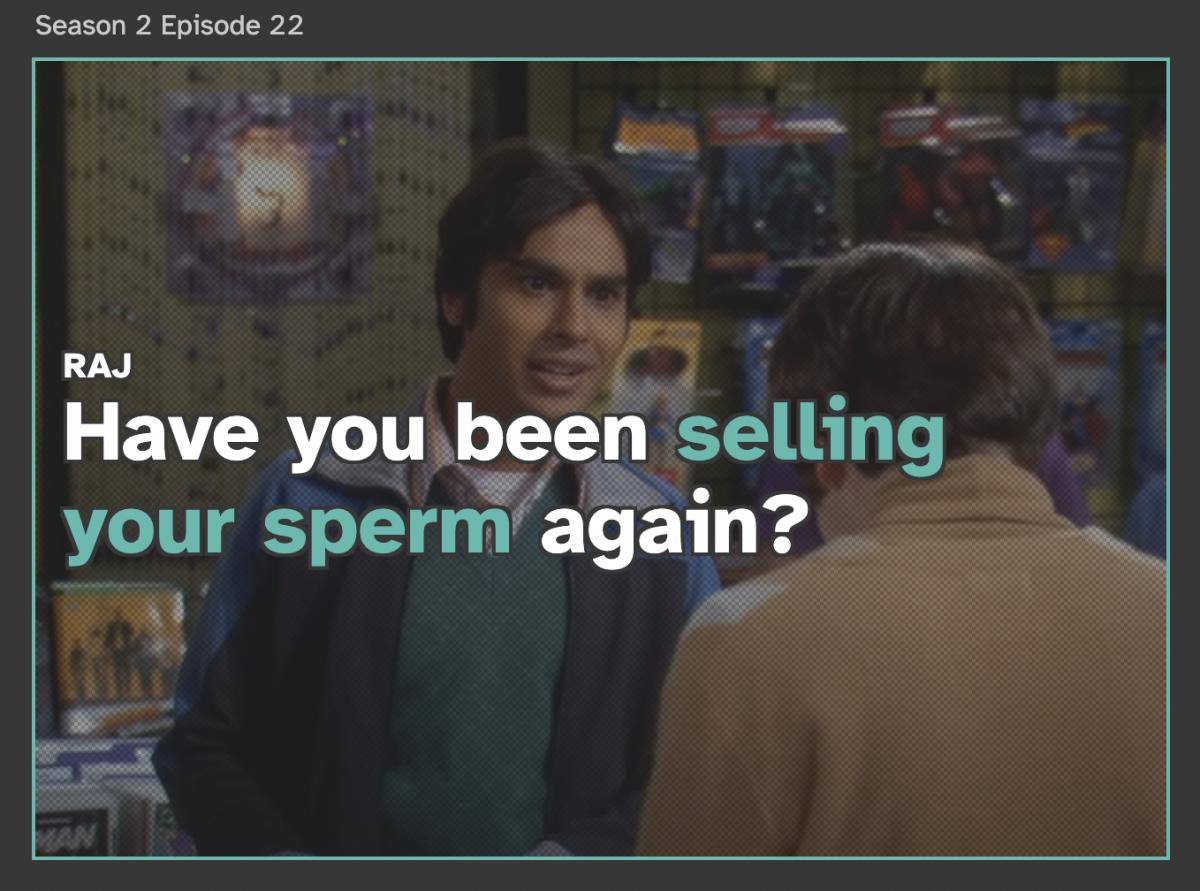

I kind of know why the sex content is the most cut out, because I think Chinese culture is more conservative than American culture. So that part makes sense to me. But meanwhile I think “Big Bang Theory” is TV-14. It’s a very healthy TV show; it’s not like “Game of Thrones.” So the part that surprised me is how sensitive they can be [in] deciding to take those things out. Some sexual jokes might be to too far, but I think some are just funny and basic sexual knowledge some middle school students should know. But the sex education is not that good in China.

And the other things are things related to China. So I know there are racist jokes, and I think that this part is the only part that makes perfect sense to me (to cut out). So the characters are making those racism jokes as a joke, but people could also be offended watching that. So I think they take that out — OK, good.

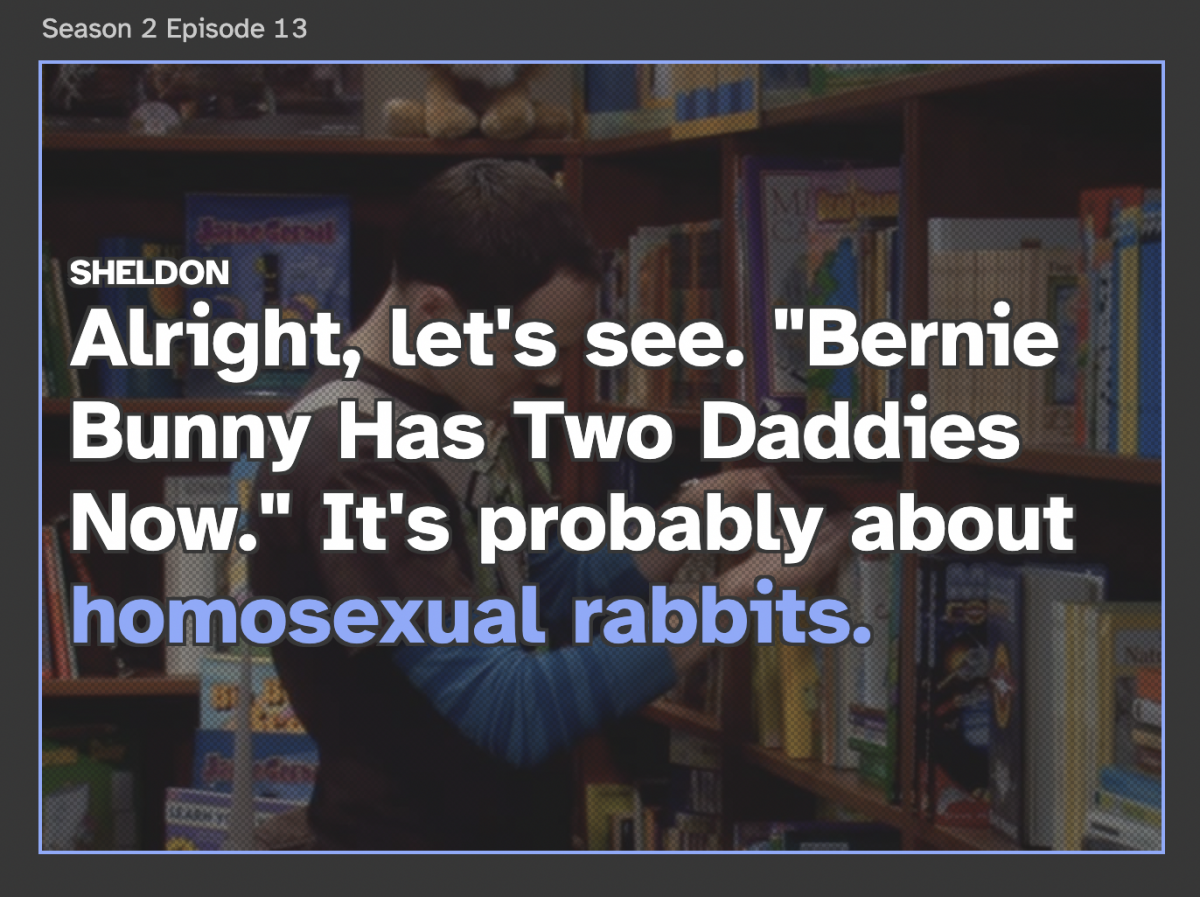

There is one thing that’s really consistent, and that is the LGBTQ+ content, like that is just straight cut. There is zero of it there… There is one joke about a book about two rabbits that are dads, and even that joke was cut out because even animals can’t be like that. I think this is too much. But also I know why they do that: it’s because LGBTQ+ groups are not protected by law in China, as many other countries do.

Who do you think gets to decide what gets cut?

In my experience, in my old newsroom (in China), I know we have in-house censors to help review comments and decide to cut them out or not. So that logic is applied to many content production companies. So for those web streaming companies, they have those censors too. Because they have to submit for review, and they don’t have many details to follow I think that they just cut a lot of it. They have laws, but the laws are kind of like general laws… They have to decide whether to cut or not… and they don’t want to have to go though all the loopholes.

Did you feel nervous about publishing this or if you could potentially get some criticism from people in China?

Yeah, I am super afraid. Can we say that, though? I don’t want to be too critical about my government because they don’t like that, but I just want to say that being born and raised in China we kind of have been taught that we cannot criticize the government even though it is a very common thing in America.

I was afraid, but I also think that this could be constructive suggestions for my government. Because the idea of this piece is not just like to say bad things about the Chinese government; it’s more like I wish they could relieve the censorship thing a bit more, because the Chinese government has been saying we’re going to boost our soft power, like cultural power. We want our cultural things like entertainment … to be more strong and more fascinating to foreigners.

So I think that my piece is still constructive because at the end of my piece I say that if the Chinese government wants its content producers to produce good TV shows — good movies, good content, good music — they have to be more tolerant. And I think they should start with allowing “The Big Bang Theory” to tell more jokes. I love my country. As a Chinese person, I want more Chinese movies, Chinese cultural products to be known by other foreigners.