How visual storyteller Alvin Chang uses cartoons to illustrate data findings

After reading an article in ProPublica, Chang decided to break down Facebook’s algorithm and explain to readers how the internet discriminates against certain users. The piece titled “How the internet keeps poor people out of poor neighborhoods,” uses a combination of his very own “cartoonsplainers” and interactive media to explain the discriminatory practices.

Storybench connected with Chang to talk about this story and how he uses data visualization to educate audiences about complicated topics — from Facebook advertising discrimination to redistricting.

Where did you get the idea for this story? How did you gather the data for it?

I had seen a piece in ProPublica where they went to Facebook and tried to advertise apartments to white people, which is definitely a violation of federal housing laws. They hit the surface of it. Obviously, you could do this on Facebook. Without many guidelines, you can still go to Facebook and advertise to people who like horseback riding, and you would get a certain demographic that you want. No one is paying attention to this.

If I wanted to advertise cars to just men, I could probably be like, “Only NFL fans who like MMA, and they can have my car.” That’s not illegal, but there are lots of versions of that that are illegal. And so, I just thought that that was my starting point. I wondered how extensive [it is] and how much people have thought about this and tested this.

It turns out it was pretty common. Even before the internet, people were trying to have advertisements for certain groups of people, especially with housing. And that led me down a rabbit hole of talking to a whole bunch of people.

Even before the internet, people were trying to have advertisements for certain groups of people, especially with housing.

Alvin Chang

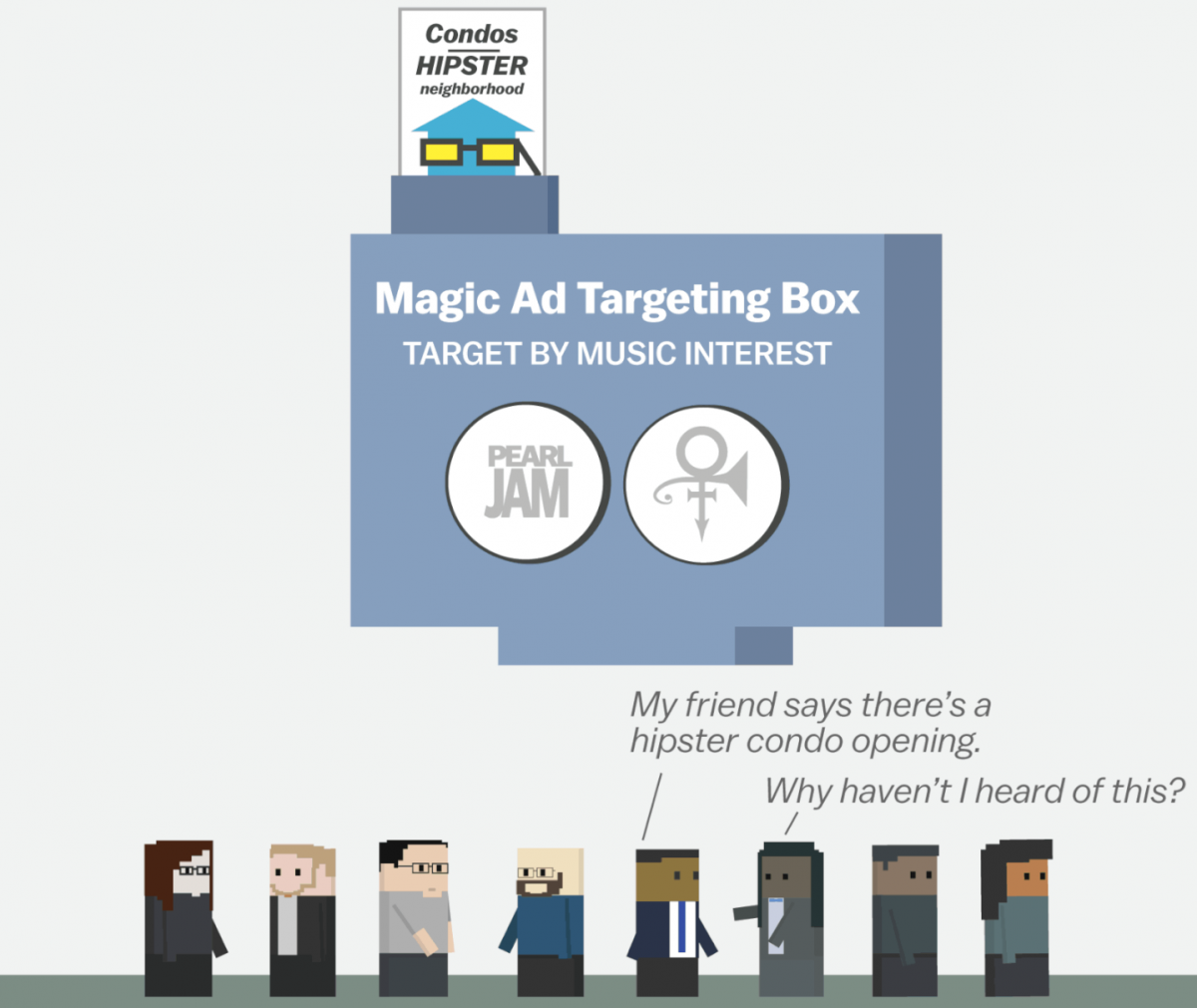

There’s actually not a ton of data [in the piece]. It’s more about helping people understand this idea of, if you’ve just advertised to Pearl Jam fans, you’re gonna get a mostly white potential resident response — versus if you were to advertise to Prince fans then that might have a more even distribution.

That was the starting point. As I started digging more and more. There was this really rich history of essentially putting us where we are today and grappling with this difficult problem of how do we prevent people from just advertising to the people that they want to, when it’s either illegal or morally not great. How do we even know that it is happening? I think on the internet, a lot of things are happening behind closed doors or behind Facebook’s wall.

I covered housing before, and I’d covered segregation before, but with this one there was no real data on it because no one’s really collected that data, and it’s hidden by Facebook.

How do you determine, with all your pieces, how to tell the story?

Usually, I try to figure out what is the one thing that my readers should take away from this story. We read so many things; you’re not going to remember everything in that story. In fact, I don’t remember everything in the story, but what is the large, big idea or a data finding that I want someone to take away from it? And I start from there.

In this piece, I wanted people to understand that if you advertise to Prince fans or Pearl Jam fans or baseball fans, or some combination of them that you can, either purposefully or accidentally, be discriminatory. It doesn’t have to be explicitly raised, and it’s a really simple concept. But I wanted to start there and then break it down. And so that was the starting point.

Initially, I thought, well, you know, I’ve got this like this weird machine right? This weird machine that I drew that makes no sense, but that’s always the starting point of how I can tell that story. And then I extrapolate out from there. All the cartoons you see interact with this machine that shows you that point, and then eventually there’s an interactive to get to that point even more fully. Everything else comes down from there.

Sometimes it’s just a chart. Sometimes it’s a chart that I’m spending the entire piece building around the chart. But it usually has to do with focusing on that one thing that I want people to remember.

This story was written in 2016. Are there any potential updates you would make based on new social media outlets and trends?

If I did it now, it would be a lot shorter. In the last six years, we are thinking a lot more about algorithms like our Facebook feeds and TikTok.

If this was specifically for an audience that understands TikTok, I think there’s a lot of knowledge that people already have. So maybe it’s like, “Hey, if I’m advertising for this apartment on TikTok, then I’m going to advertise to people who like and stay on these videos longer or follow these people more.” And I think that idea is a lot more common now. If I did it to my parents’ generation, maybe it doesn’t really make sense.

There’s a better analog there because I think with Facebook, it’s probably a little more difficult to understand what’s happening. Whereas with TikTok immediately, it’s like: I only want to advertise to people who follow and like fancy cooking channels. Immediately, I’m clearly discriminating against people who don’t have money, which is not illegal. There’s a way to get to that exact audience.

What do you think about the audience when starting a story? Is there anything specifically you think about before you go in and start designing?

For this piece, I thought it’s not for people who are super insiders. This is for people who have never really thought about this, but have maybe found an apartment on Facebook or maybe sold something on Facebook marketplace. And that was pretty broad. Sometimes it’s narrowing down to I want this to be for someone who actually understands.

So that’s the separator of like, how much knowledge you have to know before you come into this. And usually it’s like nothing for my pieces, you don’t have to know anything except to have lived in America. This story didn’t get quite as complicated, but I think there are other pieces where the expectation is you understand the topic or you know a little bit about whatever I’m writing about.

I really don’t care if you read the other stuff. If you get the basic idea then I have you hooked, but I think unless you narrow down that audience a little bit, it’s really hard to figure out what you want them to take away from it.

- How visual storyteller Alvin Chang uses cartoons to illustrate data findings - November 1, 2022