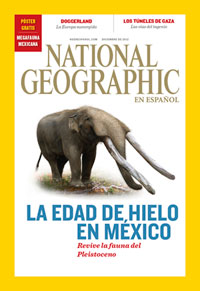

Bringing the Ice Age to life

The deep past is fertile ground for the imagination: a world of gigantic beasts and long-extinct forests, smoking volcanoes and deadly tar pits. It was precisely these fantastical landscapes and gargantuan mammals of the Pleistocene that captured the childhood imagination of artist Sergio de la Rosa who, together with his wife Reyna Luz Jasso, a sculptor, creates vivid digital artwork and sculptures that re-create a lost world.

De la Rosa has produced scientific illustrations for National Geographic en Español and Mexico’s National Council on Biodiversity (CONABIO) and has provided base art for computer graphic animators for the documentary series “Mexico en la Edad de Hielo” (Mexico in the Ice Age), produced by Mexico’s Instituto Politécnico Nacional. As a couple, they have created life-sized sculptures of Pleistocene megafauna (large animals) for museums and parks across Mexico.

De la Rosa has produced scientific illustrations for National Geographic en Español and Mexico’s National Council on Biodiversity (CONABIO) and has provided base art for computer graphic animators for the documentary series “Mexico en la Edad de Hielo” (Mexico in the Ice Age), produced by Mexico’s Instituto Politécnico Nacional. As a couple, they have created life-sized sculptures of Pleistocene megafauna (large animals) for museums and parks across Mexico.

Their artwork brings together digital technology and a profound sense of wonder about evolution. It feels like an interface between modern digital media and prehistoric rock painting.

A childhood interest

De la Rosa’s interest in capturing nature in art began as a boyhood fascination with wildlife. How do animals behave? How do they interact? His special fondness for the Pleistocene comes from a desire for the general public to learn about the fascinating animals that once lived in Mexico, ones we will never encounter: mastodons, gomphotheres, and saber-toothed cats, among others.

“It’s a fantastic world,” says de la Rosa. As an art student, he started creating paleoart for the fun of it. His first large project was a series of illustrations for the Rewilding Institute, a think tank focused on conservation. From there, he worked with biologist Carlos Galindo to create illustrations for scientific articles—like a recent one about prehistoric humans and ancient elephant associations discovered in Sonora, Mexico—and various print media.

Working for that moment of awe

De la Rosa and his wife’s work is part of an effort to introduce these ancient animals—and their biology—to the general public. In this sense, sculpture is an ideal medium: it provides a tangible proximity to the long-extinct fauna.

One of the most gratifying elements of her work, says Jasso, is seeing people’s reactions to a life-sized sculpture: they are often surprised by how much grander these animals were than how they had imagined them. On one occasion, at the Cenote de Dos Ojos site museum, the couple encouraged a young little girl to touch a sculpture of a gomphothere: she dared not get too close because she was afraid it would move. Creating this proximity and generating this sense of awe is something that motivates them to move on to bigger and more ambitious projects.

How they do it

The couple’s creative process always begins with extensive research. By studying fossils and mounted skeletons, they can infer the approximate weight and volume of prehistoric animals.

Next, the artists research the anatomy of the extinct animal’s closest living relatives. In the case of the Giant Sloth, for example, the analyzed the basic anatomy of the two extant species of arboreal sloths. Based on the similarities and differences between the two modern species, they can infer the proportions and shapes of the muscles on a much more robust animal.

Then, the artists are able to produce a sketch in two and three dimensions that can be applied to sculpture or digital art. This process allows seemingly cold, technical topics like fossil morphology to come to life.

Digital tools

Using Adobe Photoshop, 3D design with a graphic program called Zbrush, putty and resin, the artists experiment with animal forms while respecting the work of findings published by biologists and paleontologists. Technology is vital to this process: the Internet allows access not only to scientific discoveries, but also to digital tools and techniques that can be maximized in order to create a meeting point between science and art which can be easily adapted as new discoveries are made.

The artists’ illustrations and sculptures start out as two dimensional sketches in Adobe Photoshop and, occasionally, Adobe Illustrator. De la Rosa has never gotten used to drawing on digital tablets; he prefers a mouse. From there, they create 3D models in Zbrush, an intuitive platform that De la Rosa likens to working with putty or clay. Starting with a digital sphere, he can pull and mold pixels, creating spikes, shapes, and variations in volume. Occasionally, they use Adobe After Effects and Adobe Premiere for editing, but Photoshop is De la Rosa’s preferred platform for posters, calendars, and other 2D media.

Animating 3D models

Science, art and technology all came together in the series “Mexico in the Ice Age,” in which de la Rosa worked with paleontologists and digital animators at M31 Medios to recreate the region’s Ice Age, which occurred around 10,000 years ago. De la Rosa provided images to start with and, together with scientists, helped refine the appearance of the animals’ behavior and movements.

The workflow started with De la Rosa’s 3D models in Zbrush, which a team of animators transferred to Maya, 3D Max, and Cinema 4D. Each team member focused on a specific task with a specific platform. For example, one would model the animal’s extremities, another its muscles, and a third created the fur and other textures. In the end, the joint efforts created a completed piece.

Although bound by television’s time constraints, the team tried to capture aspects of prehistoric life that would most spark the viewer’s interest, giving the public a visual narrative of what is in books and scientific articles. Their objective is to help scientific research go hand-in-hand with graphic art.

“I think art and science must build these bridges where knowledge has a graphic output,” says de la Rosa. “Not everyone will be as excited as a paleoartist when they see an elephant, but it can create an interest in some people. The conjunction of art and science can help promote consciousness of evolutionary processes, of how rich the natural world is.”

We’ve always told prehistoric stories

New technologies are helping paleoartists recreate ancient worlds in dynamic, multisensory ways, seen in exhibits like St. Louis Zoo’s 4D safari where visitors interact with life-size animatronic dinosaurs. However, de la Rosa says, paleoart has been somewhat frowned upon by artists, some of whom consider it outdated or even Victorian. While contemporary art tends towards conceptual work, de la Rosa says that creating and conserving paleoart keeps us in touch with the essence of art itself. The first artists, he estimates, created cave paintings and rock art out of a sense of splendor and appreciation of the natural world, capturing their impressions of what affected them.

“A cave artist tracing an image on a wall. That is the origin of art,” says de la Rosa. With digital technologies and conceptual trends in contemporary art, more and more of that primordial artistic process has been demoted.

It shouldn’t be that way, he says. “The joy of trying to express what you love about the world, the impression of meeting with wildlife or the sense of wonder you’ve had since childhood—trying to capture that on a piece of paper, that’s what should keep manifesting itself.”

That’s how you awake in people a sense of wonder about the natural world.

That’s how you begin to tell a prehistoric story.

Michelle María Early Capistrán is a cultural anthropologist and marine biologist in Mexico. She is a frequent contributor to LatinAmericanScience.org. Follow her on Twitter at @earlycapistran.

- Bringing the Ice Age to life - August 18, 2015