Does better news coverage lead to greater voter engagement? The answer: It depends

Meaningful participation in civic life isn’t possible without access to high-quality news and information. Consider the most fundamental aspect of community engagement: voting in local elections. If prospective voters lack the means to inform themselves about candidates for the select board, the city council, the school committee and the like, then it follows that they will be less likely to vote.

But is the reverse also true? Does the presence of a reliable news source result in a higher level of voter participation?

To find out, I compared two towns, Bedford and Burlington, both northwest of Boston. The towns share a border as well as a number of similar demographic characteristics. An important difference, though, is that one town is the home of a widely read independent digital news project and the other is not. I looked at the number of candidates who have run for local office over the previous two decades as well as voter turnout in order to determine whether there were any differences that could be explained by one community having better, more comprehensive news coverage than the other.

The outcome was not what I expected. Before I get to that, though, let me offer some background on the decline of local journalism, the effect of news coverage on civic life and a description of the two towns and their media profiles.

The decline of local news

Over the past two generations, the number of small daily and weekly newspapers in the United States has declined precipitously. (By “small,” I am excluding not just national newspapers such as The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal but also large regional papers such as The Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times.) More than 2,100 newspapers closed between 2004 and 2019, according to a widely cited study by the University of North Carolina, leaving about 1,800 communities without a local news outlet. These places have come to be known as “news deserts.” Many of the papers that are left have been so depleted of staff that they are sometimes referred to as “ghost newspapers.” The Pew Research Center found that newsroom employment declined by 26%, from 114,000 to 85,000, between 2008 and 2020. As a result, local residents in many places have been deprived of the news and information they need to govern themselves in a democracy.

In recent years there have been a number of studies that attempt to show a correlation between the decline of local news and a decrease in knowledge about political candidates and issues. For instance, a study published in the Journal of Politics that looked at some 10,000 news articles covering U.S. House races showed that “newspapers published less, and less substantive, local political news” in 2014 compared to 2010. Separately, a small but measurable drop in knowledge about the candidates could be found among 9,500 people who were surveyed in 2010 and then again in 2014 — leading the authors, Danny Hayes and Jennifer L. Lawless, to conclude that “local political news is diminishing in the United States, and … citizen engagement is a casualty.”

A more direct link to civic participation was found in a study of 11 newspapers in California that documented both a decline in the number of mayoral candidates and in voter turnout as, over time, those papers offered less local coverage than they once had. The results, published in Urban Affairs Review in September 2019, were based on 246 elections in 46 cities over a period of 20 years. “Our analysis of the data suggests that as newsroom staffing declines, the competitiveness of city political races does indeed suffer,” the authors, Meghan E. Rubado and Jay T. Jennings, wrote, adding: “Overall, our findings suggest that the decline of local newspapers has serious consequences for democracy.”

The question I’ll attempt to answer is whether a similar effect can be found using a much smaller sample size and with some quirks that don’t quite fit the narrative of overall decline.

Two communities

Bedford and Burlington are suburban communities northwest of Boston, a prosperous region with an educated populace and high real-estate prices. The area, dotted with technology and biomedical companies, is dominated by Interstate 95 — formerly Route 128, known in the 1970s and ’80s as “America’s Technology Highway.” Visitors to the two communities might conclude that Burlington is more urban whereas Bedford has more of the characteristics of a small town. As the region has grown over the years, though, the differences between the two towns have diminished. Burlington is home to a large regional mall, but there are extensive retail operations in Bedford as well. Some comparisons between the two communities are provided in the following chart.

| Demographic characteristics (source: U.S. Census Bureau) | Burlington | Bedford |

| Estimated population, 7/1/2019 | 28,627 | 14,123 |

| White population | 74.3% | 77.4% |

| Black population | 4.5% | 4.1% |

| Asian population | 16.8% | 15.0% |

| Latino/Hispanic population | 3.1% | 3.8% |

| Owner-occupied housing | 73.6% | 73.9% |

| Value of owner-occupied units | $533,800 | $655,300 |

| Number of households | 10,001 | 5,312 |

| Persons per household | 2.76 | 2.58 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 56.9% | 71.8% |

| Median household income, 2015-’19 (2019 dollars) | $118,721 | $128,354 |

| Per capita income in past 12 months (2019 dollars) | $51,248 | $62,831 |

| Land area in square miles | 11.73 | 13.66 |

| Population per square mile | 2,087.8 | 975.3 |

Note that with the exception of overall population, higher education and population density, there is extensive overlap between the two communities. Commonalities are strong in the case of the two towns’ racial and ethnic mix, property values and per capita income.

Both communities also have similar governmental structures. The highest governing authority in both Burlington and Bedford is town meeting, the classic New England institution by which the citizens of the community get together several times a year to decide on the major issues facing the town and to approve the annual budget. Burlington’s town meeting, like those of a number of larger communities, is elected — 126 residents run for three-year terms. Bedford has an open town meeting by which any resident of the community may show up, take part in debate and vote.

The two communities are governed on a week-to-week basis by smaller groups of part-time elected officials — a select board and a school committee of five members each. Those two panels, in turn, hire and supervise full-time professional executives. Burlington has a town administrator; Bedford a town manager. Although the two positions are similar, a town manager has more independent authority than a town administrator, according to Bedford Town Clerk Bridget Rodrigue. Each town has a superintendent of schools.

Both towns have a variety of other elected and appointed officials to handle matters such as zoning, development and budgeting, but the select boards and the school committees have the highest profiles. The two communities hold their annual elections in the spring, which means that they do not coincide with national or state elections. Turnout, therefore, depends strictly on voter interest in local offices.

The media environment

The most significant difference between Bedford and Burlington is that Bedford has a robust nonprofit website that provides comprehensive coverage of the community. The Bedford Citizen, founded in 2012 by three members of the town’s League of Women Voters, covers the select board, the school committee and other governmental groups as well as local events and publishes feature stories on a variety of topics. Overall, the Citizen publishes about 20 stories a week.

According to its 2019 FormEZ filed with the Internal Revenue Service, the most recent available at GuideStar, the organization reported more than $87,000 in revenues, mostly in the form of grants, donations and sponsorships. The Citizen employs a full-time managing editor, a part-time reporter and a part-time operations manager and pays freelance fees to reporters who cover various governmental meetings and events. (Information obtained in an August 2020 interview with Teri Morrow, then-president of the Citizen’s board and publisher, now executive director; Julie McCay Turner, managing editor and co-founder; and Meredith McCulloch, co-founder, as well as in an August 2021 email exchange with Turner.)

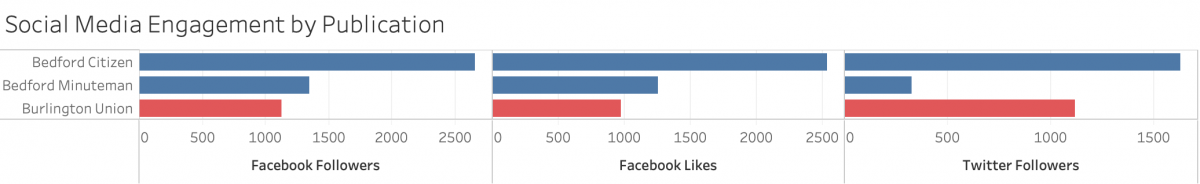

The Citizen measures reach in a variety of ways. According to internal data provided by Turner, the website received about 467,000 page views for the first six months of 2021, an increase of more than 20% over the same period in 2020. The site also recorded about 133,000 users in the first half of 2021, a rise of nearly 50% over the previous year. Its daily newsletter — compiled automatically from its RSS feed along with a manually edited version sent out on Sunday mornings — had 2,027 subscribers on May 31, 2021, or about 38% of the 5,312 households in the community, with an open rate that often reached as high as 60%. (It is not known how many of those 2,027 subscribers live out of town or live in the same household as another subscriber.) In August 2021, its Facebook page had 2,543 likes and 2,660 followers, and its Twitter feed had 1,634 followers.

The other significant new source in town is the Bedford Minuteman, a once-independent weekly newspaper now owned by Gannett, a nationwide chain with about a hundred daily papers and about a thousand weeklies. Known for drastic cost-cutting, Gannett publishes most of the small community newspapers in Eastern Massachusetts.

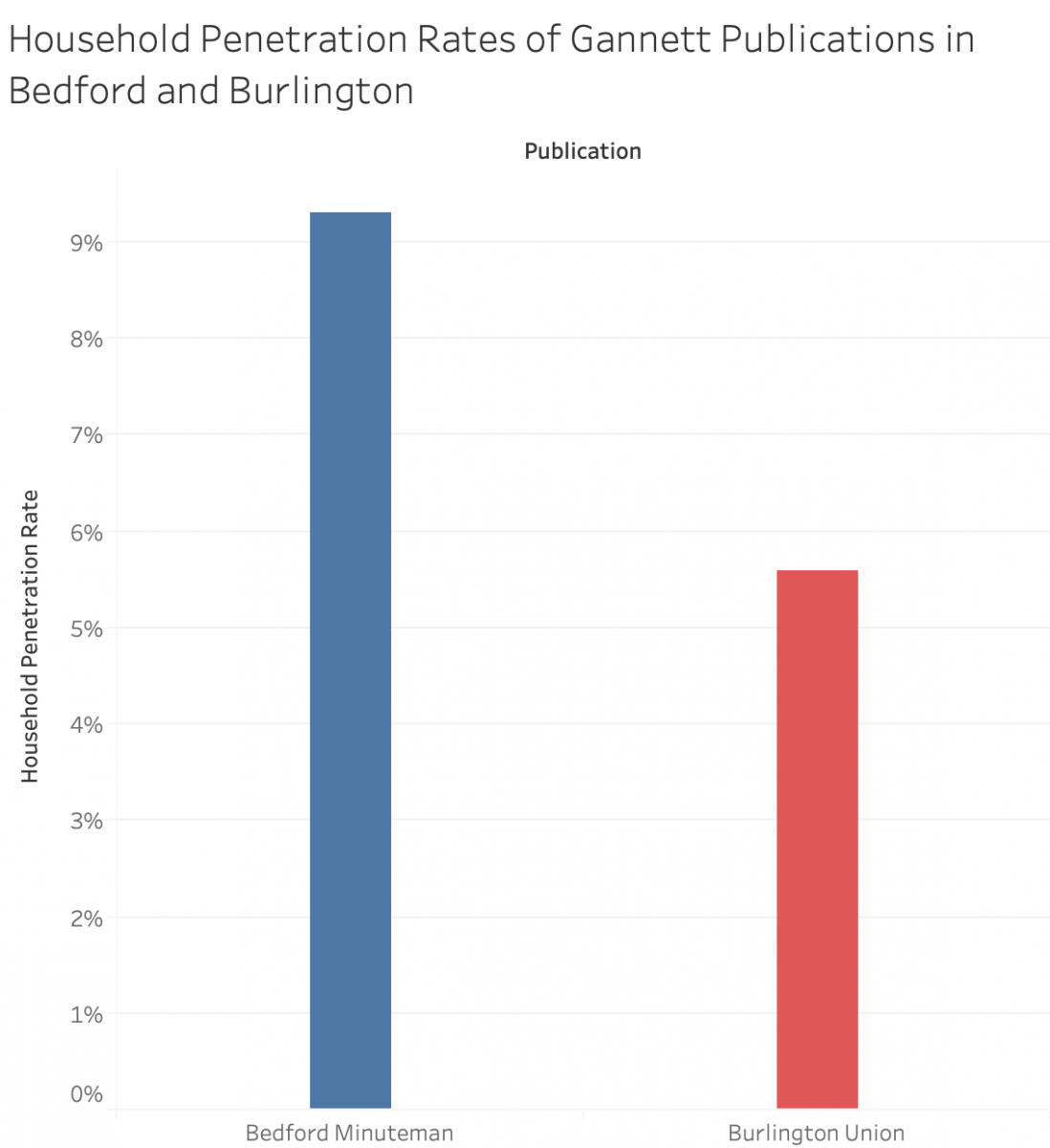

In line with that minimalist approach, the Minuteman provides barely a fraction of the news that is published in the Citizen. For example, an examination of the four editions published in May 2021 revealed about a half-dozen staff-written news articles with any sort of Bedford angle. According to numbers filed by Gannett with the Alliance for Audited Media, paid circulation of the Minuteman for the six-month period ending March 30, 2021, was 493, for a household penetration rate of 9.3% (with the caveat that some subscribers may live outside of Bedford). In August 2021, the paper had 1,256 likes and 1,346 followers on Facebook and 325 followers on Twitter.

Bedford also has a Patch.com site, mainly comprising press releases and announcements from Bedford as well as regional news. Bedford also has a local access cable television station, which does not cover news but rather provides some public-affairs programming produced by volunteers.

Although Burlington lacks a local news source with the reach and comprehensiveness of The Bedford Citizen, it does receive more coverage from traditional sources than Bedford.

For one thing, the Gannett paper, the Burlington Union, fared considerably better in a scan of its four weekly editions from May 2021. I counted 20 staff-written news stories that were either wholly about Burlington or that had a significant Burlington angle. It is possible that the presence of The Bedford Citizen has led Gannett to cut the resources that it devotes to the Bedford Minuteman. In any case, the Burlington Union is considerably more robust than the Minuteman. Paid circulation, though, is another story — at 561, its household penetration rate is 5.6%, well below that of the Minuteman. As of August 2021, the Union’s Facebook page had received 976 likes and 1,128 followers, and its Twitter feed had attracted 1,117 followers.

Burlington also receives some coverage from the The Daily Times Chronicle in nearby Woburn, which publishes on a Monday-through-Friday schedule. In perusing about a dozen issues of the paper in August 2021, I detected on average one staff-written story a day on Burlington topics such as governmental affairs, restaurant openings and business news, along with a few press releases. The Daily Times Chronicle does not report its circulation, and in any case it would be difficult to determine how many copies are distributed in Burlington.

As with Bedford, Burlington has a Patch.com site and a local access cable television station.

One final caveat. Both the Bedford Minuteman and the Burlington Union offer online editions, and as Gannett continues to close print newspapers it has increasingly emphasized digital subscriptions. The circulation figures that Gannett reports to the Alliance for Audited Media, however, do not include digital reach. “We do not share site specific subscription data,” said Gannett’s corporate communications office in response to my email inquiry seeking digital metrics for the Union and the Minuteman.

Given that the websites for both papers require a paid subscription and include multiple stories that are regional rather than local, it is probably safe to assume that the impact of those websites is minimal. In any case, the Bedford and Burlington newspapers are on a more or less equal playing field with regard to their digital presence.

Measuring citizen engagement

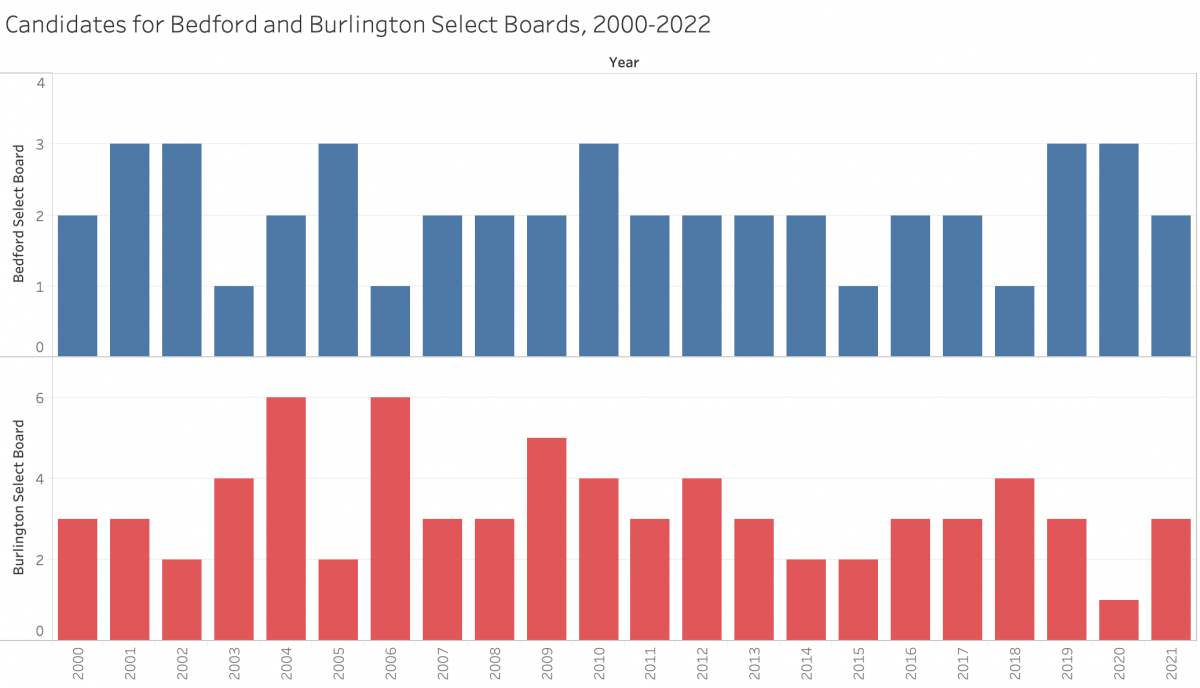

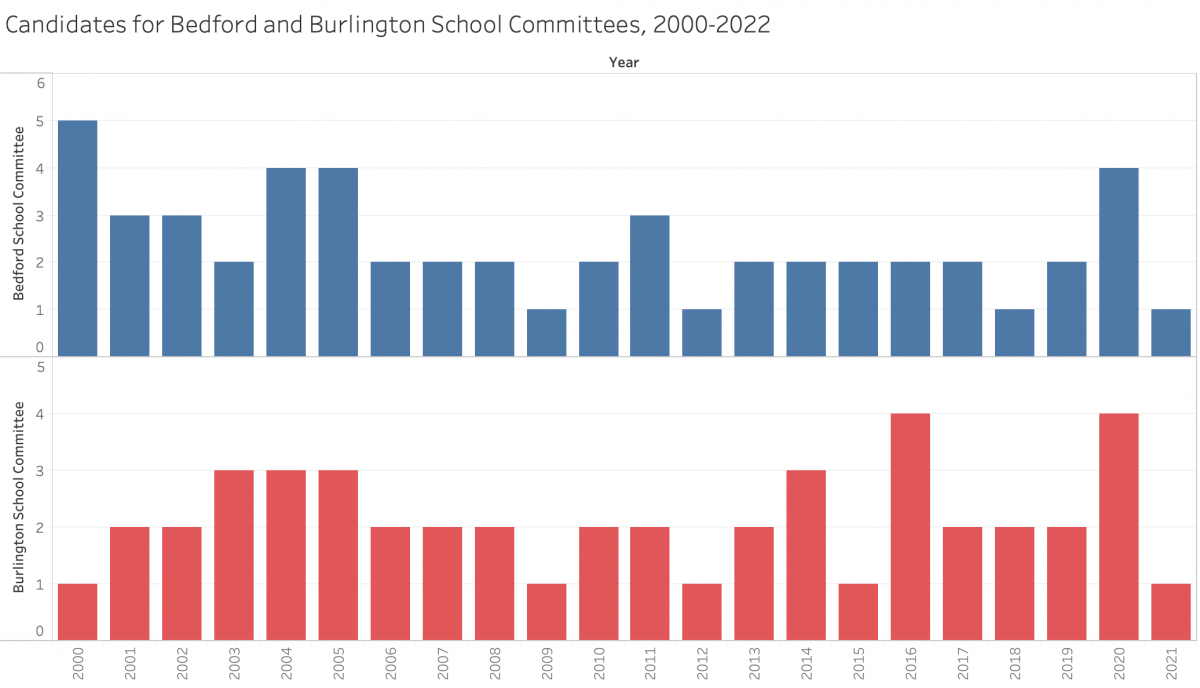

Citizen engagement was measured by examining the number of candidates in the two communities for the select board and the school committee, the most prominent elected panels in each town, and by comparing voter turnout between the two towns in their annual municipal elections held each spring. The data below are based on annual town reports published in both communities and on email communications with the town clerk’s offices. First, the number of candidates.

| Year | Bedford Select Board | Bedford School Committee | Burlington Select Board | Burlington School Committee |

| 2000 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| 2001 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 2002 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 2003 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| 2004 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| 2005 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 2006 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 2007 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 2008 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 2009 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| 2010 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 2011 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 2012 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 2013 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 2014 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 2015 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 2016 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2017 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 2018 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 2019 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 2020 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 2021 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Totals | 46 | 51 | 71 | 47 |

Despite less news coverage, Burlington actually had more candidates running for local office than Bedford — 118 to 97, or nearly 22% more. Nor do we see any increase in the number of candidates running in Bedford starting in 2011, when The Bedford Citizen was founded.

There is one caveat about Burlington’s comparatively higher numbers. In 18 of the 19 years between 2000 and 2018, the same gadfly candidate ran for select board, always coming in last. The problem with small sample sizes is that such oddities can have a large impact on whatever conclusions might be drawn. If that candidate is eliminated, then the number of people running for the select board in Burlington comes down from 71 to 54, with the total number of candidates dropping to 100, or about 3% more than Bedford. That’s an insignificant difference. Even so, any conjecture that Bedford might have been more politically active than Burlington – especially after the Citizen was founded and began to grow – is not borne out.

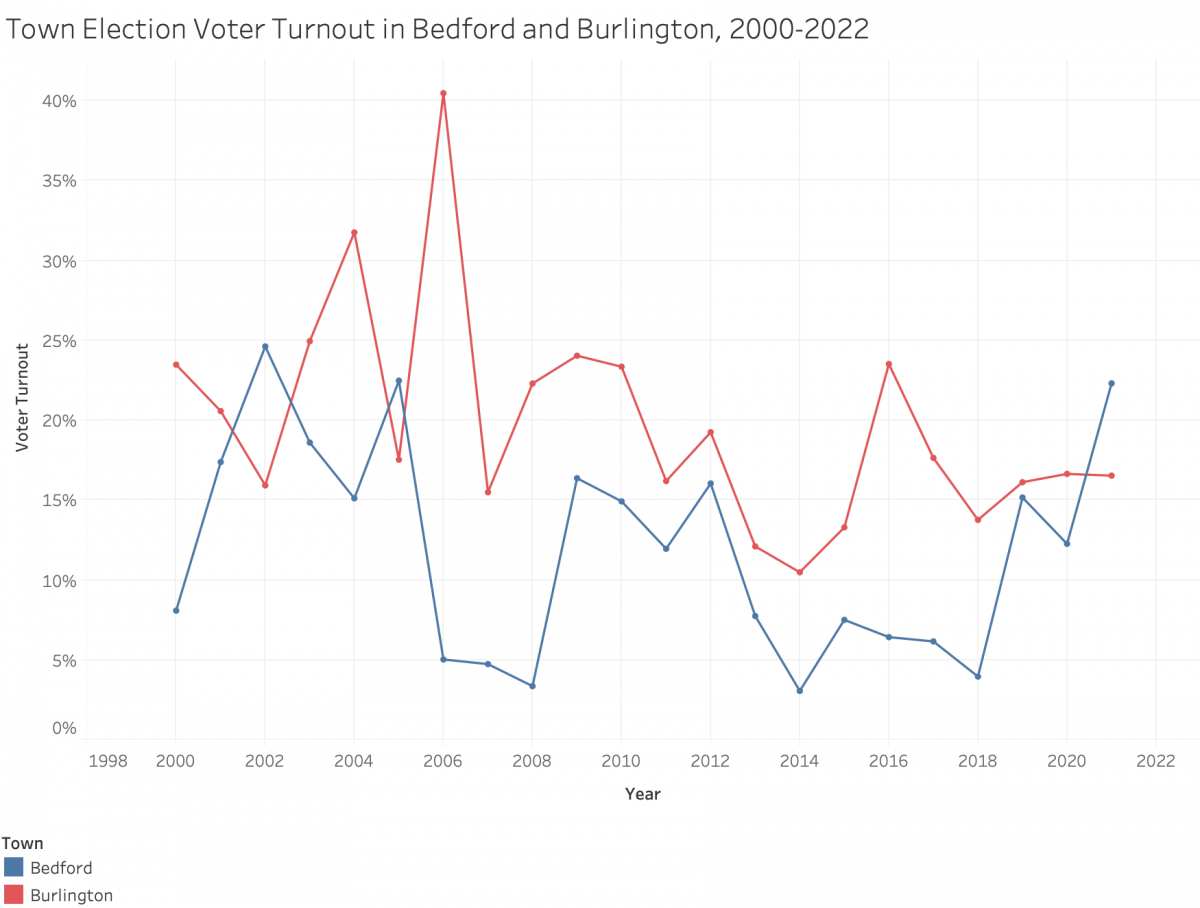

Now let’s look at voter turnout.

| Year | Bedford | Burlington | ||||

| Votes Cast | Registered Voters | Turnout | Votes Cast | Registered Voters | Turnout | |

| 2000 | 672 | 8,295 | 8.10% | 3,292 | 14,006 | 23.50% |

| 2001 | 1,496 | 8,596 | 17.40% | 2,944 | 14,295 | 20.59% |

| 2002 | 2,104 | 8,540 | 24.64% | 2,197 | 13,787 | 15.94% |

| 2003 | 1,553 | 8,341 | 18.62% | 3,472 | 13,904 | 24.97% |

| 2004 | 1,293 | 8,547 | 15.13% | 4,418 | 13,900 | 31.78% |

| 2005 | 1,958 | 8,703 | 22.50% | 2,488 | 14,176 | 17.55% |

| 2006 | 439 | 8,717 | 5.04% | 5,593 | 13,811 | 40.50% |

| 2007 | 412 | 8,669 | 4.75% | 2,168 | 13,980 | 15.51% |

| 2008 | 301 | 8,927 | 3.37% | 3,210 | 14,384 | 22.32% |

| 2009 | 1,552 | 9,469 | 16.39% | 3,599 | 14,956 | 24.06% |

| 2010 | 1,386 | 9,276 | 14.94% | 3,473 | 14,861 | 23.37% |

| 2011 | 1,129 | 9,433 | 11.97% | 2,405 | 14,835 | 16.21% |

| 2012 | 1,517 | 9,448 | 16.06% | 2,921 | 15,160 | 19.27% |

| 2013 | 764 | 9,844 | 7.76% | 1,897 | 15,652 | 12.12% |

| 2014 | 299 | 9,753 | 3.07% | 1,599 | 15,230 | 10.50% |

| 2015 | 735 | 9,769 | 7.52% | 2,005 | 15,065 | 13.31% |

| 2016 | 618 | 9,593 | 6.44% | 3,713 | 15,776 | 23.54% |

| 2017 | 629 | 10,189 | 6.17% | 2,908 | 16,465 | 17.66% |

| 2018 | 388 | 9,774 | 3.97% | 2,177 | 15,793 | 13.78% |

| 2019 | 1,521 | 10,021 | 15.18% | 2,703 | 16,749 | 16.14% |

| 2020 | 1,240 | 10,094 | 12.28% | 2,760 | 16,571 | 16.66% |

| 2021 | 2,317 | 10,377 | 22.33% | 2,875 | 17,371 | 16.55% |

| Totals | 24,323 | 204,375 | 11.90% | 64,817 | 330,727 | 19.60% |

| 2000-’11 | 14,295 | 105,513 | 13.55% | 39,259 | 170,895 | 22.97% |

| 2012-’21 | 10,028 | 98,862 | 10.14% | 25,558 | 172,049 | 14.86% |

The pattern we saw with the number of political candidates in the two communities is even more pronounced with voter turnout. Even though Bedford receives more news coverage than Burlington, voter turnout in Burlington over a 22-year period was actually higher in Burlington. That holds true for 2000-’11, before the founding of The Bedford Citizen, and for 2012-’21, when the Citizen was publishing and growing. The only findings that might correlate favorably with the rise of the Citizen is that there was only a 4.72% gap in voter turnout between the two communities in 2012-’21 compared to a 9.47% gap in 2000-’11. The numbers are too small, though, to be able to state with any confidence that superior news coverage had an impact.

If news coverage appears to have had little or no effect on differences in political participation between two communities with many demographic similarities, what could be the explanation? There are three possibilities.

• By far the most likely explanation is that Burlington has an elected town meeting whereas Bedford’s is open. With 126 elected town meeting members serving three-year terms, at least 42 seats are on the line every year. The campaign for town meeting permeates every part of Burlington, with candidates asking their friends and neighbors to vote. This creates quite a different dynamic from what prevails in Bedford, where any resident is allowed to show up at town meeting and participate. Thus there is considerably more election-related energy at the grassroots level in Burlington than there is in Bedford.

• Although The Bedford Citizen is the most comprehensive news source in either of the two communities, with substantial reach for a digital-only publication, Burlington is better served by established newspapers. Of Gannett’s papers, the Burlington Union contains considerably more coverage than the Bedford Minuteman, although I did not make an assessment to determine how that may have changed over the years. The Daily Times Chronicle has been covering Burlington since at least the 1970s. Bedford may receive more and better coverage than Burlington because of the Citizen, but Burlington residents may be receiving what they perceive as enough to feel reasonably well informed.

• There may be unexplained differences in the political cultures of the two communities — which, again, demonstrates the problems of attempting to make sweeping claims on the basis of such a small sample size.

Conclusion

Meaningful political engagement at the local level is impossible without access to quality news and information. Previous studies show that knowledge about congressional candidates declines in proportion to shrinking news coverage and that less coverage may have a negative effect on the number of candidates who run for office and on voter turnout.

It may turn out, though, that the effect is too subtle to be measured when the sample size is small and when there is background noise in the form of differences in the communities being measured. Despite the presence of a high-quality, widely read community website, The Bedford Citizen, political engagement in Bedford was lower than in Burlington. There was no meaningful difference in the number of candidates running for local office when we adjust for the presence of a single gadfly candidate who ran in multiple elections in Burlington. But voter turnout was markedly higher in Burlington than in Bedford, even in the years after the Citizen was founded.

A study that comprised more communities would even out some of the differences between Bedford and Burlington. Ideally a number of communities with strong local news coverage would be compared with a number that lacks such coverage.

Another factor, not explored here, is the role of social media in the form of citizen-led Facebook groups, Nextdoor posts and the like. Is there a difference in civic engagement between communities whose social media are of reasonably good quality and those overrun by trolls and hate speech?

Regardless of the findings presented here, the local news crisis represents an ongoing threat to democracy. In many parts of the country, there are no local news sources at all. What I found shouldn’t obscure that reality. Bedford may be covered more comprehensively than Burlington, but they are both receiving at least some coverage. The need to find ways of providing local coverage in news deserts is of paramount importance.

- Does better news coverage lead to greater voter engagement? The answer: It depends - October 13, 2021

- A group project in the age of COVID: What worked, what didn’t, and what we learned about making it better - February 3, 2021

- For journalism students reporting on climate change, a self-taught lesson in teamwork - October 19, 2018