How Kate Sosin told the story of transgender individuals in California prisons

How often do transgender people get the opportunity to tell their own stories at major media outlets? According to Kate Sosin, LGBTQ+ Reporter for The 19th, organizations with a particular focus on queer stories focus on bringing marginalized voices to the front. Queer media is expanding, and historically underrepresented groups of journalists use their lived experience to bring powerful, inclusive journalism to the people. Not only does this mean that transgender journalists can tell trans stories on their own terms, but in some cases, it affords them additional access to advocate on others’ behalf.

Sosin was freelancing for NBC Out, the company’s LGBTQ+ vertical, when they published “Trans, imprisoned — and trapped.” Having reported on other prisons before, Sosin felt so strongly about the housing conditions of transgender people that they began filing Freedom of Information Act requests (FOIAs), and pressing correctional departments to fulfill legal obligations to their incarcerees. As a transgender person themself, they were uniquely able to educate and advocate to these correctional departments.

Storybench spoke to Kate Sosin about why “Trans, imprisoned — and trapped” largely interviewed transgender individuals in California prisons, the process of undertaking a massive investigative piece with data visualization and video components, and PREA, the Prison Rape Elimination Act.

What was your initial inspiration for this piece?

I started reporting on a case about Lindsay Saunders-Velez, a trans woman who was incarcerated in Colorado. In 2018 she said that she had gone before a judge, asked to be moved for her safety because she was at risk of sexual assault, and the judge denied her request to be moved. Hours later, [she] was sexually assaulted in prison. I covered that story for Into, where I was, which was the LGBTQ publication owned by Grindr at the time. It was just the worst case of prison abuse I had ever read. It was so bad that I wasn’t able to describe all of the legal complaints because I thought it would traumatize readers. I couldn’t get it out of my mind. I called Lindsay’s attorney, Paula Greisen, the same attorney who brought the Masterpiece Cakeshop case to the Supreme Court. I just started talking to her, and she said, “I don’t think Colorado has ever housed a trans woman according to her gender.” That ended up being true, and she [Paula] said, “this is a problem in every state.” Which I knew it was, because I had reported on other prisons. I got laid off from Into, and I was freelancing. I had nowhere to work for, but I felt so strongly about this, knowing that this would be a story because I knew PREA required that people be placed on a case by case basis. So I decided that if I just started filing the FOIAs, I would get a story. And if I got a story, someone would want to take it.

How did you pitch this piece to NBC?

I started freelancing at NBC Out, which is the LGBTQ vertical. I pitched it to NBC Out, and my editor there, Brooke Sopelsa, was like, we definitely want this but it’s too big for NBC Out. It needs to go to Enterprise, which is the investigative unit. The investigative unit took it and also brought it into broadcast and assigned a video production team to it. I went and did the interviews for the video, with Brock [Stoneham] who produced the video. The reporting that’s in the video–the numbers, the statistics, the info–was all of my reporting.

You said that this all started in Colorado. Was there a reason the piece focused on Chino, California?

Kate: In trying to find out what was happening with the case in Colorado, I wanted to understand some other prison policies, and I felt like I heard a lot about what was happening in California. I heard that California had lawsuits and I also knew that California had settled a lawsuit involving a trans person trying to access gender affirming medical care. So I called the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and their spokesperson was like, “well, if you wanna know, why don’t you come into the prisons? Come to San Quentin [State Prison].” I was just floored that she would invite me, and so I went to San Quentin. She just gave me a lot of access, and gave our video team a lot of access. They gave us so much access and let us interview directly without them present, people who were incarcerated, that we located the story in California.

Considering the conditions that these women had, it’s honestly shocking that they gave you so much access.

So–yes. California just passed a new law that basically enforces PREA for trans people and goes further. And as bad as it sounds, California is ahead of other states. So I think that when they invited us in, they did really feel like they didn’t have anything to hide. They felt like they have done well and they’re continually trying and this is a step toward transparency. And that they just want to present things honestly. I don’t know that they expected the story that we told, but they also–I would imagine that if we went to other states, it would be even worse than what we found in California.

And how did they react to the story that you told?

I never heard anything from them on that story. I’ve worked with them now for a couple years, and I’ve worked with them on stories since, and they’ve been just as helpful, responsive, and professional on those stories as they were with this first story.

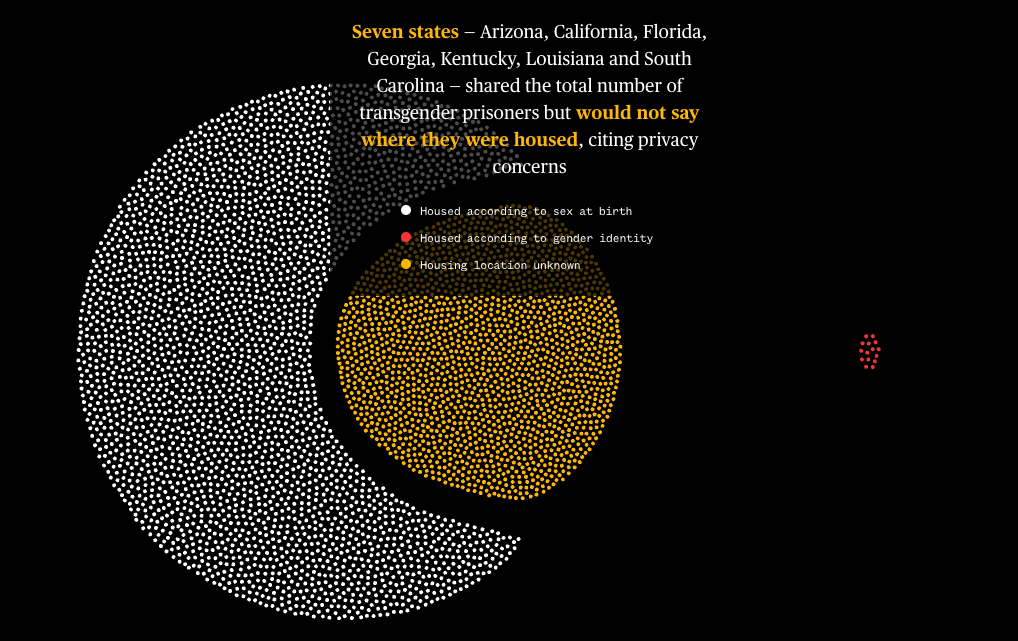

NBC has some awesome data visualization that went along with that piece. How did that come into being?

NBC put a lot of resources into this reporting. One of the things they decided to do early on, which I was very grateful for, was to just put a data team behind this. They had really top notch folks working to turn the data that I had into something that people could visualize, that would have high impact when you looked at it. I had an editor, several editors really, who fielded how that would look. We had a lot of conversations about what we thought would be an impactful way to tell this story. We decided that would be both video and text, and that these data visualizations would be a component of that. The reporting took more than a year and then the process of actually putting the story together took months also, because we were fact checking everything, putting together the data piece, editing the video, everything went through standards and legal, it was just a huge undertaking to do a story like this.

Since this piece came out right before the COVID crisis really hit us, has the reception been what you hoped?

That’s a funny question. I never really imagined a reception, I guess. I just do the work and then hope it’s good. I would say yeah, a lot of people responded to it and shared it. It was on the top of Apple News, which was nice. I felt like a lot of people saw and read it. Which was great, I wanted people to know about this issue and people continue to read this story. Because we just don’t think about the humanity of incarcerated people, and especially trans incarcerated people, and trans incarcerated people of color. The reality of not being able to live in your gender and being sexually abused over and over and over again, is so horrifying that it really keeps me up at night. I felt like that story had to exist and I’m glad it does.

Have any corrections departments made adjustments based on your coverage?

Not that I know of based on this story. But I have done other stories where I will ask questions and immediately after I start asking questions, things change for people in anticipation of a story being published. For example, I just did a story for The 19th with my colleague Ko Bragg about how the California Department of Corrections’ largest female prison was keeping COVID positive folks with COVID negative folks. As soon as we did a media inquiry on that, they stopped doing it, even though they had been doing it for weeks. It happened in Florida, reporting on a woman I had been corresponding with for more than a year, “I hear that she doesn’t have access to canteen items that reflect her gender,” and she would write me and be like, “all of a sudden I have all those things that I was asking for.” A lot of times I will put in these FOIA requests and just put them in as my name. They didn’t know I was a journalist, I just filed a FOIA request. And then by and large, I did not hear back from these agencies in the manner that they were required to respond. I would follow up, and be like, “Hi, I filed a FOIA request from you, this is for NBC News, and if you do not respond you’re gonna hear from our attorney.” And then I would hear back within hours. Or even if I didn’t threaten to sue, I would be like, “this is NBC News,” and then I’d hear back. I just wondered what the experience was of a regular citizen trying to get that information.

I think there’s a lot of pressure on trans journalists to explain transness 101 and justify our existence. How did you move past that into reporting on the real issues we face?

I think in the beginning that was harder. I have had the luxury of almost always working in queer media, and it wasn’t until I was laid off from Into that I really went into mainstream media. At which point, people were like, excited that I was a trans person reporting on trans people. It’s so interesting because I think being trans used to be the thing that prevented me from getting work, right? It was always really hard for me to get jobs, and to be a journalist. Now it’s the thing that people seek out about my work. It’s honestly very interesting and powerful to be able to walk into a setting like a prison, or wherever, and say, “hi, I’m Kate Sosin, I’m with NBC News, I’m reporting on trans issues,” and it’s really hard to make a transphobic comment to NBC News when the reporter is transgender. Legacy media now is hiring trans people to tell trans stories. I had so many instances in reporting this story where the agency was like, “well, we have 36 transgender men and 2 transgender women.” And I would be like, “are you sure you’re not mixing those up? Because actually, it’s almost always that there are more trans women in custody.” We would go through this thing back and forth and they would give me a hard time, and I would be like, I am a transgender person. You don’t get to be transphobic on the phone. I’m a trans person and also I’m working for a major media organization, and the power of that felt honestly great. To know that you have the support of a major news organization, that historically has not been the case. Because NBC has NBC Out, NBC is really well trained in these issues. Their standards and legal department knows how to check for these things, and they’re not gonna give you pushback. It’s such a different conversation when you can call up a department of corrections and say no, actually, it’s this. So I don’t feel like I’m at that point anymore, of having to prove my humanity as a trans reporter. I just won’t accept that conversation.

Is there anything else about this story that you think I haven’t touched on or that you think is important?

One thing I would say is after nearly all of these stories I heard reports–and it was difficult to confirm–that the people we talked to were retaliated against. I would caution anyone who does that reporting to really consider that, to have that conversation with a source, and make sure that source is aware of that. They probably are, but to really be super careful about how those conversations are happening and what they look like, because it’s very dangerous for people to talk to the media when they are incarcerated. If it’s not done well, it can have really severe consequences for people.