How the Allen Coral Atlas is mapping and monitoring coral reefs worldwide

Although coral reefs occupy less than one percent of the ocean floor, their importance extends well beyond their size. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that 500 million people survive on coral reefs for income, and their economic value in the U.S. is estimated at $3.4 billion each year. More importantly, healthy coral reefs reduce wave energy by 97%, which weakens storms before they hit shorelines.

Yet global warming, overfishing, and other human activities are threatening the health of these reefs. Unlike other underwater species, the reefs’ nature does not allow them to relocate to higher latitudes or further depths to adapt to increasing temperatures, which is why they are more vulnerable to higher mortality rates to the extent that they might disappear one day.

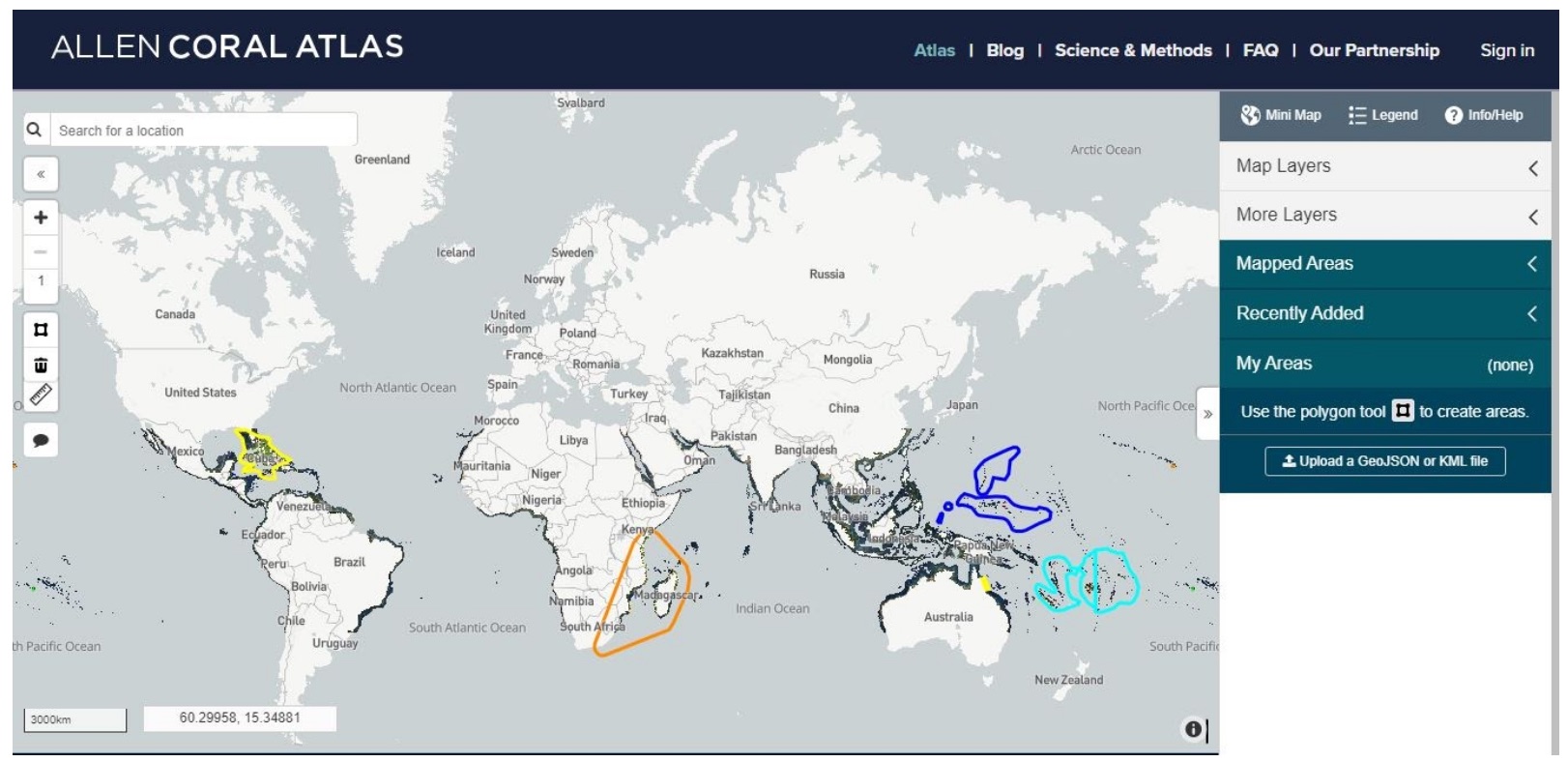

Among the first steps in mitigating their extinction is mapping out exactly where the world’s reefs are located. The Allen Coral Atlas project – an international collaboration between Arizona State University, University of Queensland, the National Geographic Society and Planet Labs, with funding from Microsoft founder Paul Allen’s company Vulcan, Inc. – is doing just that. The Atlas has produced the first global map of coral reefs habitats worldwide. The idea is to then use these maps to help make decisions regarding reef restoration or protection in light of limited funding.

“It is to help people make those decisions in an ecological and spatially explicit way which right now is not possible for coral reefs really anywhere,” said Gregory Asner, the director of ASU’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, whose team contributes to the mapping and leads the monitoring system for the mapping project.

Storybench spoke to Asner about the maps being created, his role in the project and the conversations that the project is hoping to spark.

Have you been a part of this project since the very beginning?

Yeah, I co-founded the project. I am in charge of all the data cleaning, all pre-processing but I am also in charge of the monitoring system overall. ASU is the lead for the entire monitoring system—my program, and then we have Planet—they provide data; that is their role. University of Queensland does some map generation and National Geographic is helping with the outreach. That is the exact partnership.

I started it with several people two years ago. We just had our two year anniversary last month. We have another year to finish. It is not launched yet; you can see it online but it is only partially populated with data because we are rolling it out as we finish it. The Allen Coral Atlas has two major parts: the maps and the monitoring system. Those are different. The maps are where a coral reef is, and you can see where we finished those maps.

And then the monitoring system—you do not see it, we are just weeks away from launching it. That is the system that updates every week and tells us the condition of the reefs. Whether they are bleaching or whether they are not bleaching and so forth. So, the maps and the monitoring are complementary products that are not the same. You just haven’t seen it yet because we haven’t put it there yet.

Are the systems updated in real time?

The monitoring system will be updated every week with Planet data. We use a variety of satellite data, but Planet is the main one. So we are using more than 200 satellites from Planet. We bring the satellite data in, my team, I guess the word is cleans the data but it is more like processes the data. Then we do what is called reflectance, calibration and the seafloor bathymetry from it, which is how deep the water is.

Then we pass our products to the University [of] Queensland and they use our products to generate new maps of where the reef is. That is all those maps really define. And then the second system—the monitoring system that we are about to launch—has a capability of, with the Planet data, detection of whether a reef is bleaching or not—becoming whiter or not.

Is there a huge difference reflected in the data itself when bleaching has occurred?

Yeah, it follows the name bleaching. A reef gets overheated from ocean warming in what we call a marine heat wave. When that happens, the coral turns from browns and blues and greens and yellows to white. And that indicates that the reef has bleached. We have created the very first capability for detecting that from Earth’s orbit. It has never been done before. It is not online yet but I am getting close to launching it. I’ve been working on it for years.

Is it possible to detect the reefs that existed once upon a time but no longer exist right now?

From the standpoint of if a shallow reef area has died, yes, we see that it was there and that is now dead. But if the reef has to be obviously in the satellite record. It has to have occurred in the last few years. Planet data are really only three years old.

How big are the datasets that you receive?

Well, for the Planet, for all the whole world’s reefs we are talking about, terabytes and terabytes of data. So it is a major computing job.

Is there usually a lot of noise present in the data?

Yeah, satellites have their own noise, meaning the actual imaging systems onboard the spacecraft are not perfect. Also, the atmosphere has a lot of features that generate what you might call noise like clouds of course, but also just water vapor and then the sea surface itself generates issues that you might consider noise like waves and what we call sun glint. Kinda like looking into the mirror into the sun and it blinds the satellite momentarily.

So there is an array; these are just examples of issues that we have to solve. Now we have an automated processing system that takes in all of these data and goes through all those issues and generates the cleanest possible data for each week.

How much of this process is automated and where does human involvement become necessary?

Mostly troubleshooting now. It is highly automated, but because it is still data, we find issues. I was imaging in the Indian ocean recently and just the way the water, we call turbidity—the color of the water was different for a few days and we just hadn’t seen that before. We had to manually understand it and fix it. It is one of those things where we are still discovering variation on the earth’s surface that we don’t necessarily know about ahead of time. That generates kind of a manual analysis of what is going on rather than the fully automated system.

Are there periodic datasets for the same place?

The map of where the reef is, is a one time dataset. That is the outline of the reef so that’s not going to change very fast. But the monitoring system that I’ve described to you is every week, everywhere. We want to see how the reefs are changing every week. The maps, in the end, become a kind of static part of the project and the monitoring system is the dynamic, week-to-week part of the project.

What sorts of conversations is this project hoping to spark among the public?

There are some public education parts that we are building as well. Next year, ASU will roll out what is called the Coral Atlas Education Program or Coral Atlas Ed. That is to teach people about coral reefs and the changes they are undergoing. That is important, of course.

Equally important is the system that we are building is going to become part of a decision support system for decision makers. I am a conservation ecologist so I work with governments and NGOs and I help them make decisions about their reefs. The decisions tend to be focused on the good, the bad, and the ugly. [Those] are the words that people use. Where is the good part of the reef that we should protect, where is the bad part of the reef that we should restore, and where is the ugly—the really really troubled parts of the reef that we just don’t have the money to fix or to work on. It helps them to focus on where to apply limited resources, limited funding to protect, restore, and in some cases, just say we can’t fix that area. That is what the mapping and monitoring is really about. It is to help people make those decisions in an ecological and spatially explicit way which right now is not possible for coral reefs really anywhere.

I live in Hawaii, and the Hawain islands that I work in…I mean, I do lots of projects here with the state government and they just don’t have maps to support the actions that they want to undertake. Then you go to the reef systems in the Indian ocean and the coral triangle region around Papua New Guinea, north of Australia, and even reefs in the Carribean; so many are virtually unknown. Managing them, making decisions about them to protect, restore, or let go are impossible now and The Allen Coral Atlas is going to generate that possibility.

Can’t the reefs in the “ugly category” be restored or improved in any way?

Not really. I have decades of work on reefs and there are vast areas that have been so degraded by human activity. It is super expensive to restore reefs. Extremely expensive. You got to pick and choose your battles. It is an unfortunate situation but the monitoring system that we are building is going to allow for people to focus on areas that can be worked on because many of those that are in the “bad” category go unnourished and then they become the “ugly”. We are trying to cut off the process of the areas that could be restored being neglected by accident and then they become too far gone and we can’t get them back.