How The New York Times used drones and maps to visualize Hurricane Harvey’s impact on Texas

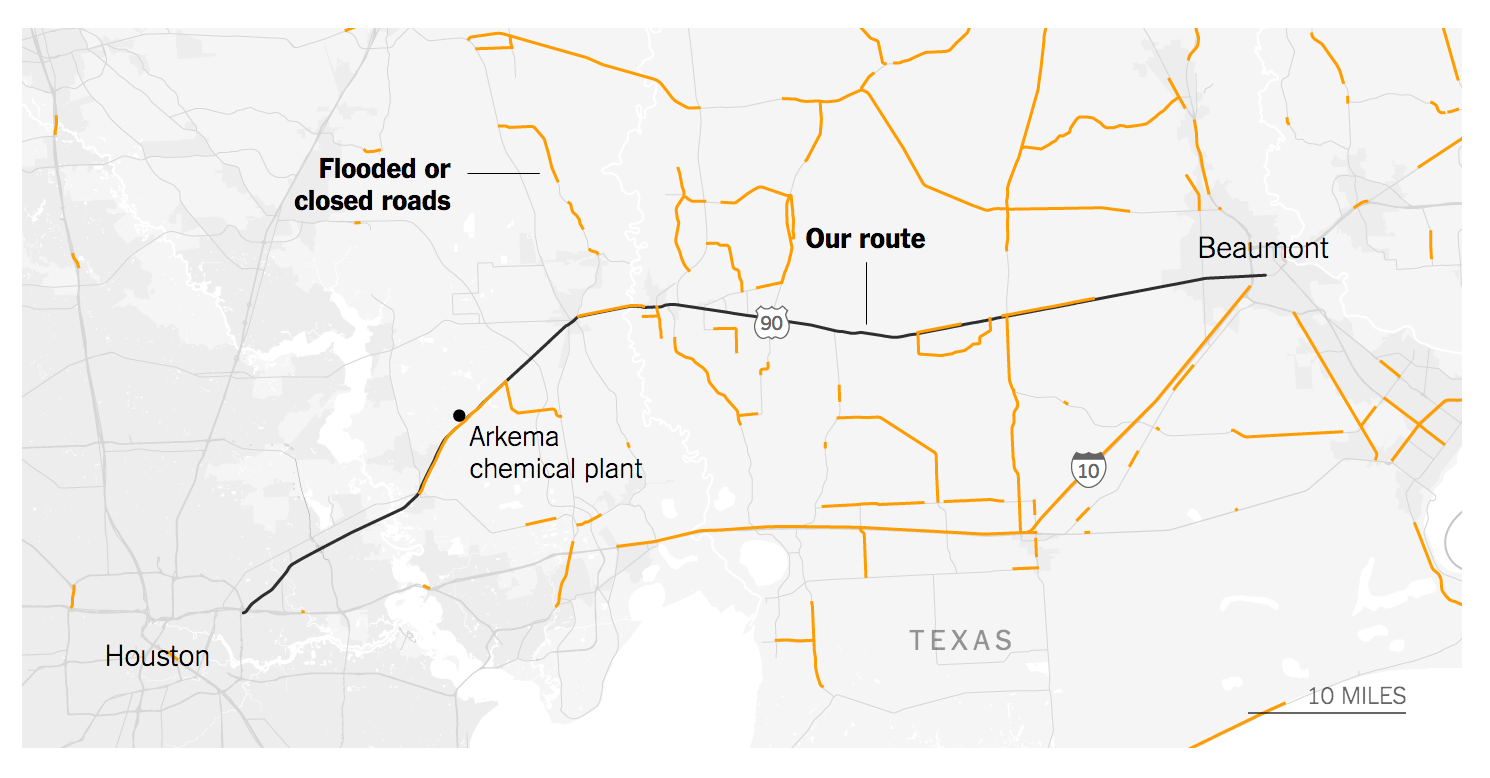

During the height of the flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in Texas, The New York Times sent two of its reporters to document the damage. Tim Wallace and Derek Watkins, who happen to both be cartographers and geographers, decided to use maps, drone footage, short videos and still images to document the drive from Houston to Beaumont which, under normal circumstances, would be a two-hour drive.

The drive ended up taking them days. The final piece, “Town After Town Under Water in the 100 Miles From Houston to Beaumont,” conveys the flooding and sense of uncertainty that they encountered along the way. Storybench spoke with Wallace about how the project was envisioned, the techniques he and Watkins used and the challenges they faced.

How was this project envisioned?

Derek and I were flown down to Texas on that Monday, as the flood waters were still rising, but the storm was over. We spent a whole day in Houston in a neighborhood, taking photos and interviews. When we got back we asked our editors what they wanted us to do, but there were other people doing what we were doing, and they were better at it. They’re journalists and photographers, and we’re geographers, and we’ve never covered something like this before. At that point, we wanted to come up with a project that leaned on our skills. That’s when we decided to drive up and document some of the most affected towns. Beaumont was the worst off because it was caught between two waves. It rained when the hurricane first hit, and then it curled back over it. We thought it would be interesting to see if it would be possible to get there and tell the story. When it was pitched it took a bit; there was a lot of scrambling. Then we spent three days in the field.

What made you decide to focus on the highways?

The idea was to try to imagine what it was like for people to get from place to place. The roads were often flooded, many places were blocked, and from there we had to reroute. We wanted to explain to readers what the reality was, how blocked off they were, and how they couldn’t really evacuate. How, for family members that wanted to get to them, what was usually a two-to-three hour drive could take days. It wasn’t meant to be about infrastructure, but that’s really how you get there.

The use of overhead shots was particularly impactful. Why did you decide to use them?

Derek thought of making a geographer’s log of what was happening. From there we decided to use a top-down approach to explain. The most obvious place to use the drone was over the one- to two-mile stretch of highway that was completely flooded. So we sent the drone up to see if we could see the other side. When we couldn’t, it was pretty telling of the extent of the flooding. We also shot over a neighborhood, mainly to focus on the progression. What it would be like to walk one block and have it be completely normal, unflooded, and then walk another and see it underwater.

What kind of challenges did you face while trying to complete the story?

The whole project was a logistical challenge. We had the office in New York keeping an eye on things for us. There was a flooded chemical plant on our way, and we had them looking at it to make sure that we weren’t anywhere near it when it blew. When you’re going into flood zones, you really need to make sure you have the right equipment and the right car. A Honda Civic definitely would not have worked for us. Field work is really just a logistical challenge. Most of the trip, it wasn’t legal for us to fly the drone. There was a flight ban in effect, mainly for the first responders and the president, and it doesn’t always make sense to fly. But we really had to keep an eye out, to make sure we were following the law. It was a back and forth of logistical hurdles. There wasn’t reliable internet out there, so we weren’t able to follow the news. We really had to trust and rely on our editors, and those back in New York, to guide us in the right direction.

Anything surprising?

I’ve never been in a flood zone, at least not to this extent, and I’ve never seen anything like it. You wouldn’t believe the flooding, unless you were there. Texas is really flat, and you would expect for the water to just stay and be everywhere you looked, but that wasn’t how it was. It made no sense, and the water was completely unpredictable. We would drive in one direction, and the water would come and go. One moment we’d be driving through a lake, and the next there would be no water in sight. Really, everything out there was a surprise.

You have another article about a submerged neighborhood. How did your techniques differ between the two projects?

The neighborhood piece came about because we were scrambling for a few days. We spent a day out on rescue boats and trucks in Houston, and decided to video that day. Everybody was incredibly matter of fact. People were walking around with bare feet in the middle of this sewage infested water. At this point it had been flooded for a while, and it was going to be for the foreseeable future. People were just going about their everyday business in the middle of a flood zone. At that time, it was their new normal. We really didn’t know if we were going to make a story out of it, it came out of nothing.

Was there anything left out that you would have liked to incorporate?

“Most of the trip, it wasn’t legal for us to fly the drone.”

No, not really. Maybe if we had time to do another piece, we could’ve added in some more photos and videos. We really weren’t sure if what we were doing had been done, so we really trusted the editors to guide us in the right direction. It worked out pretty well. A lot of the behind the scenes stuff is good, but not for another article.

If you were going to do a follow-up story, what would you do it on?

I’m not sure if there would be. It wouldn’t really be worthwhile. But the video on the neighborhood might be an interesting follow-up. It would be interesting to watch the recovery of Memorial [in Houston]. It’s possible that there’s still water there now, and what the families are doing there could warrant some attention. I don’t really know how they’re doing, it’s been a few weeks since I was in Texas, but following their stories would definitely be something.

What advice do you have for journalists that want to cover natural or even manmade disasters?

It’s really helpful to just talk to people. It doesn’t have to be on the record, it could all be on background. People were just sitting and waiting, and you don’t really know what they’re waiting for. Often it’s a ride, other times a family member, but many wanted to talk. It’s a form of catharsis, you know, therapy. Some people weren’t ready to talk, and that was ok, it was still just too fresh. But really, talk to as many people as possible, just to get a sense of the situation from the people that experienced it.