How The Washington Post turned a year-long investigation into a graphic novel

In August, The Washington Post unveiled vivid findings from a year-long investigation into a disturbing secret at the Smithsonian Institution. To help the powerful story reach a new audience, they used a nontraditional storytelling method: the graphic novel. The Post has experimented with this format before, in stories such as “The Mueller Report Illustrated.”

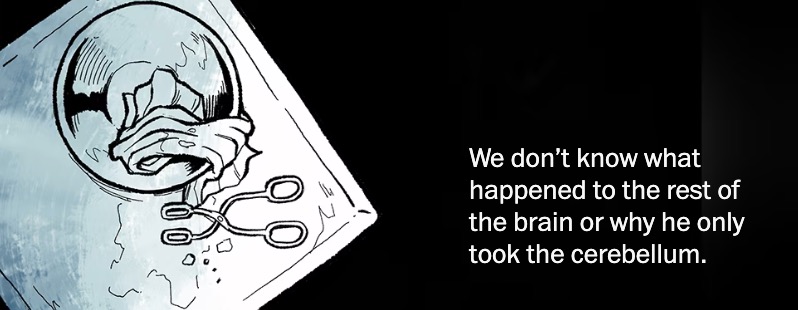

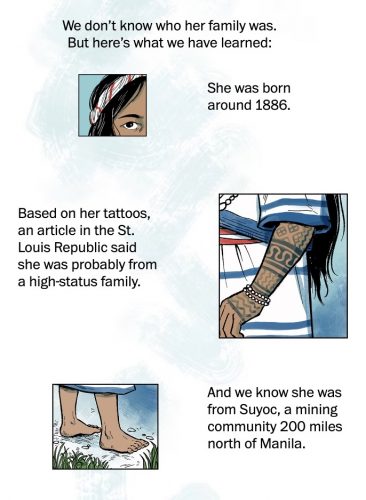

Since 1903, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., has held a massive collection of human remains, including 255 brains. One of these brain samples belonged to an Indigenous Filipina woman named Maura, who was brought to the United States from the Philippines to be displayed at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis but died days before the fair started. (While the Smithsonian Institute could not verify it was her brain, records suggest that it is hers. Her body has not yet been located, the Post reported.)

Nicole Dungca, an investigative reporter at The Post, and her team chose to tell the story. Searching for Maura is told through stunning illustrations that take readers on a journey from the Philippines, to the 1904 World’s Fair and back, spanning over 100 years. In addition to the graphic novel, The Post also created other complementary multimedia pieces to support the entire investigation, such as a podcast and a video, and shared how it was created.

“Mainstream American media doesn’t usually tell these stories,” said Dungca, who is of Filipino descent. “It’s rare to really see a Filipino story on the front page of a major newspaper, and so we took that responsibility very seriously.”

Storybench sat down with Dungca to discuss reporting Maura’s story and visualizing it as a graphic novel.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How did this story land at your desk?

Dungca: It’s a fun story, actually. One of my colleagues, Claire Healy, was freelancing the story because she’s a copy aide at The Post. Healy found this story, partly because of Janna Añonuevo Langholz, who’s in the story. Through the course of trying to report about her, Añonuevo Langholz talked about these brains.

So, I learned a little bit more about it and how at least four of the brains who had been in the collection had been from Filipinos who were brought to the 1904 World’s Fair. And for me, it was immediate: We need to get involved. I’m on the investigative team, so that usually means I get to work on big projects for months at a time. And when I just learned more about this collection, I told Healy, “We have to work on something big for this — it’s such an interesting story.”

How did you make the decision to present this story as a graphic novel?

We realized we had information on Maura because she was written about in the newspaper. For a historical story like this, there were a lot of missing pieces.

We felt like something illustrated could help fill in some of the blanks. We didn’t have her diary or contemporaneous notes, so a lot of what we had to do was use information from other people from that time to approximate what her experience was like and what the experience of all the other Filipinos who came to the U.S. was like.

The visual enterprise editor, Jenna Pirog, immediately put together that this would be a good visual story because of how we could illustrate things that weren’t necessarily photographed at the time. Also, it would allow us to tell the story in a way that told the reader off the bat: “These are the things that we know, and these are the things that we’re still unsure about.” That’s much easier to do in a comic format because of the way that you can narrate the story. We were researching things to make it as accurate as possible so that it really did reflect what happened, but by making it an illustration, people knew that it was almost like a reenactment in some way.

How did you and your team reckon with these unknown details, especially given that the search for her body is still ongoing?

In the illustrations, we wanted to show that this was clearly a guess, in some ways. That’s why, for example, you’ll only see a portion of her eye or her hair. That was a deliberate choice by the illustrator, with direction from us, about being able to show what we don’t know.

By having Ren Galeno do her illustrations in a way that could show what is fragmented, what is clearly like an artistic take on some scene, you’re able to have some version of the scene that also signals to the reader that this isn’t exactly what it looked like, but that we did enough research so that there are elements of this that are very true.

What did this story personally mean to you?

The idea that I can see my family’s native language in the pages of The Washington Post from a story I wrote about Filipinos is very surreal. It’s something I never thought I would see and that I’m really proud to have been part of. It’s not just me — there were 14 Filipinos who had a hand in this project in some way. And it’s because we felt a connection to the story and a responsibility to tell this correctly.

I’m not Kankanaey, so I was learning a lot about this. I felt a really strong responsibility to make sure that we were representing that culture correctly, that we were getting the perspective of the communities that were affected. I went all the way to the Philippines to Suyoc to tell these communities face to face because we knew these are upsetting stories. We wanted to make sure they knew that we felt like this was important and that this was something that deserved the kind of resources we put toward it.

The Post used several multimedia formats to tell Maura’s story. Why were there so many ways this story was told?

We knew not everyone was not going to look through a graphic novel. We knew that there would be people on YouTube who loved watching videos. There was the idea that we could make a video version of this — it just seemed so obvious to do so. And then because we also had a Filipino version of this [story], we knew we also had to make the Filipino version of the .

We wanted to translate it into Filipino because we wanted to make sure that the whole Filipino diaspora was able to access it, and that it would hit as many communities as possible who care about this.

What has the response been like?

It’s been a great response from the communities that have been featured [in the larger investigation]. One of the best compliments we’ve all heard is that people will say, “Oh, my middle schooler is reading the comic,” which is exactly why we did the comic. We wanted to get readers who might not typically want to read a 5,000-word text piece, which I love writing, but a comic is a completely different immersive experience.

So for people to say, “Oh, my kid loved that comic. They read it all the way through, even though they don’t typically read other parts of The Washington Post,” that’s really powerful to us to know that we are reaching people who wouldn’t typically engage with our journalism.

- How The Washington Post turned a year-long investigation into a graphic novel - October 19, 2023

- How The Washington Post’s Angel Mendoza uses Reddit to seek out new audiences - October 12, 2022