What we learned from three years of interviews with data journalists, web developers and interactive editors at leading digital newsrooms

Newsrooms don’t follow a standard playbook. They scramble, they adapt, they make mistakes. But are there some go-to tools and best practices worth adopting, whether you’re a data reporter, newsroom manager, or journalism educator?

Over the last three years, Storybench, a website from Northeastern University’s School of Journalism’s Media Innovation graduate program, has interviewed 72 data journalists, web developers, interactive graphics editors, and project managers from around the world to provide an “under the hood” look at the ingredients and best practices that go into today’s most compelling digital storytelling projects.

There are a bunch of lessons we’ve learned through our interviews – published today in this working paper – that might help chart the way forward, especially for journalism schools. They boil down to three key areas of emphasis: 1) highly networked, team-based collaboration; 2) an ethos of open-source sharing, both within and between newsrooms; 3) and mobile-driven story presentation.

As professors at Northeastern, we think it’s worth matching up newsroom needs and emerging practices with educational goals. Certainly, creating modular recipes for the journalism classroom has helped us immensely and we continue to use them in our courses. We hope you will, too. To borrow some terminology from the software movement, it may be worth downloading industry best practices and parsing top digital journalism case studies in the classroom.

[embeddoc url=”https://storybench.org/docs/collaborative-open-mobile-whitepaper.pdf” download=”all” viewer=”google”]

The full spreadsheet of interviews can be viewed here.

Below, a condensed version of our working paper:

Collaborative, Open, Mobile: A Thematic Exploration of Best Practices at the Forefront of Digital Journalism

Beset by secular market pressures and presented with a dizzying array of new technologies for news-gathering, publishing and distribution, news media outlets have undergone a sustained period of upheaval. The tools, techniques and approaches involved in data journalism and digital storytelling remain diverse and continue to evolve, and they are often highly specific to the particular journalistic outlet, story or task involved.

One of the substantial challenges, and indeed barriers to entry, for professionals, teachers, and students is trying to understand what is important to know in order to advance their skills in a targeted way. Simply put, the field can seem overwhelming in the multiplicity of options, running from different workflow processes to programming languages and applications. There remains a need, therefore, to update and consolidate knowledge of industry patterns as the field evolves and a rough consensus forms around certain procedures and takes hold across a range of newsrooms and affiliated media institutions.

As Katherine Fink and CW Anderson noted in their 2014 report “Data Journalism in the United States: Beyond the Usual Suspects,” certain “enabling factors” – the size and resources of news organizations, for example, as well as constraints such as the lack of time, funding, and tools – can influence and shape the practices and operating principles of, for example, data journalists. The process of gathering meaningful data, analyzing it, then developing this output into a compelling editorial product requires extensive labor resources and specialized, often scarce, intellectual capital. Such resource demands and constraints are indeed factors across all areas of digital journalism practice.

All this presents a challenge to anyone attempting to generalize a set of emergent “best practices.” However, our survey of current news practices revealed several developments that are lowering the barrier to entry faced by smaller outlets.

First, important conferences such as those run by Investigative Reporters & Editors, National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (NICAR) and SRCCON continue to make it easier for journalists to map out and learn certain fundamental skills. The propagation of this knowledge is creating a positive feedback loop that further accelerates the dissemination of specialized skills and knowledge. Second, an increased adherence to “open source” norms and practices means that both the tools and the knowledge required to produce high-quality digital journalism are freely available. Finally, even the commercial software and hardware required have seen dramatic declines in price.

First, important conferences such as those run by Investigative Reporters & Editors, National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (NICAR) and SRCCON continue to make it easier for journalists to map out and learn certain fundamental skills. The propagation of this knowledge is creating a positive feedback loop that further accelerates the dissemination of specialized skills and knowledge. Second, an increased adherence to “open source” norms and practices means that both the tools and the knowledge required to produce high-quality digital journalism are freely available. Finally, even the commercial software and hardware required have seen dramatic declines in price.

A review of the relevant literature reveals a range of valuable efforts to identify and categorize the tools, platforms and practices that will persist after the digital dust settles. However, current newsroom routines and workflows at the intersection of data-oriented reporting and design/visualization – how stories are “built,” so to speak, from beginning to end – merit more empirical study.

Methods

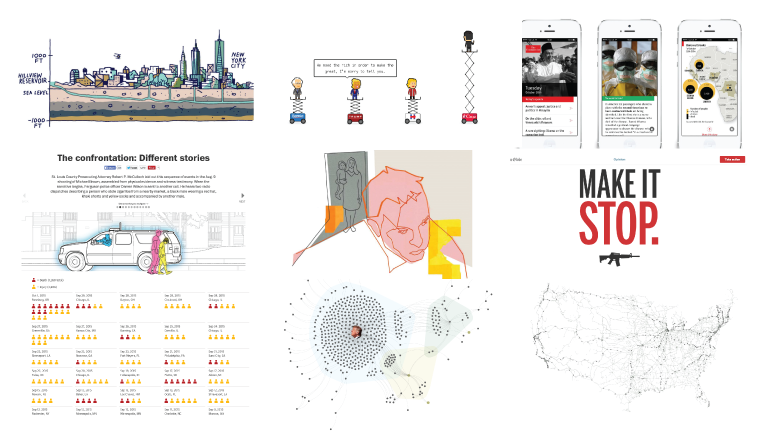

Conducted from 2014 to 2017, the interviews corresponded with the release of new journalism projects, graphics, stories, news apps or other media products that came to the attention of the Storybench editors as particularly intriguing or impressive efforts to advance digital and data-driven storytelling.

The aim was to unpack the techniques, thinking and applications behind the news products in question. The interviews were intended both as “how-tos” and as case studies in the practice of contemporary digital journalism, graphics and interactives; they sought to reveal the technical dimensions of the projects in question while also probing at the makers’ philosophies behind the production.

The newsrooms surveyed included: The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, BuzzFeed, Vox, Financial Times, Los Angeles Times, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Bloomberg News, The Boston Globe, PBS NewsHour, Quartz, Berliner Morgenpost, Seattle Times, Al Jazeera, Center for Public Integrity, Mother Jones, The Texas Tribune, the Associated Press, WBEZ, WNYC, WBUR, Monomagazine, Localore, Pictoline, Dadaviz, Corriere della Serra, Portland Press Heraldand The Guardian.

Reviewing these interviews in aggregate, we coded recurring areas of emphasis as they related to best practices in digital publishing, such as:

- Common obstacles overcome (e.g., how to make responsive charts in JavaScript).

- Techniques learned, adopted and disseminated to others passed on (e.g., Juicer for pulling in social media feeds).

- Digital tools and frameworks that are being adopted (e.g., the stylesheet language SASS).

- Makeup of successful interdepartmental collaborations (e.g., a veteran editor working with a digital graphic designer).

We then clustered these recurring themes into some broad categories with the idea of providing a general guide to what is actually going on in newsrooms at the present moment. Of course, the results are derived from a non-probability sample of industry practice. But by studying the practices and philosophies of some leading practitioners, we can begin to arrive at some loosely defined, but nevertheless discernible categories of routines and procedures that suggest important shifts in professional norms.

Results

Based on the interviews analyzed, three recurring themes emerged: Collaborative, open and mobile. Of course, not all of the issues and areas of concern surfaced in any given interview, but the sample was large enough to identify common patterns, which are explicated in the following sections.

Collaborative, team-based story-building

There is a legend in journalism that the key to digital success is hiring a newsroom unicorn: an individual with a multifaceted skillset who is equally exceptional at reporting, programming, shooting video and designing graphics. In practice, this model is seldom a reality; a far more collaborative and distributed workflow characterized the digital projects featured in the 72 Storybench interviews studied for this paper.

There is a legend in journalism that the key to digital success is hiring a newsroom unicorn. In practice, this model is seldom a reality.

Successful digital newsrooms employ talented people with diverse skillsets and, perhaps more importantly, construct collaborative environments in which these players can work together as a team.

The traditional newsroom Balkanized production into departments – design, photo, research, city, sports, classes – and organized the prevailing workflow according to Taylorist principles in which ideas and always moved in one direction on a kind of information assembly line. By contrast, the successful digital newsrooms revealed in our Storybench survey allow nimble, multifaceted teams to self-organize, coming together organically to produce an editorial product, then gathering up into new configurations according to the dynamic needs presented by both world events and editorial discretion.

There is generally an identified “project lead” to coordinate the process, but the creative drive relies on practices borrowed from disciplines like design: brainstorming, human-centered design, iteration, collaboration, rapid prototyping, user testing and an open process that doesn’t shut out ideas or personnel.

One example is The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize finalist “Chasing Bayla,” which had a team comprising a reporter, an editor, a photo editor, a video editor and a developer in addition to a project manager with enough fluency to communicate effectively with all teammates to leverage the best each medium had to contribute.

One example is The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize finalist “Chasing Bayla,” which had a team comprising a reporter, an editor, a photo editor, a video editor and a developer in addition to a project manager with enough fluency to communicate effectively with all teammates to leverage the best each medium had to contribute.

Laura Amico, Chasing Bayla’s project lead, is fond of using a mission statement to organize her team: “That way the reporter and the developer can trust one another because they have the same mission even though they ‘speak’ different languages.”

The Wall Street Journal’s “How Trump Happened,” which visualized large amounts of polling data and involved a politics editor, graphics editor and a news app developer, and The Center for Public Integrity’s “Unequal Risk,” where editors, reporters and coders worked together to visualize government data and in-depth interviews on workplace chemicals and cancer risk, demonstrate these project management practices and are examples of multidisciplinary teams at work.

The Wall Street Journal’s “How Trump Happened,” which visualized large amounts of polling data and involved a politics editor, graphics editor and a news app developer, and The Center for Public Integrity’s “Unequal Risk,” where editors, reporters and coders worked together to visualize government data and in-depth interviews on workplace chemicals and cancer risk, demonstrate these project management practices and are examples of multidisciplinary teams at work.

These patterns suggest that educators, students and professionals looking to gain skills and experience in data, design, visualization and interactive journalism production would be well served to consider the inextricably social nature of the workflow. They might strongly identify positions in the chain of what might be called “networked story-building” where they want to contribute.

The new open-source ethos

The data journalists, web developers and interactive graphics editors currently employed in the world’s leading digital newsrooms tend to subscribe to an altruistic ethos not unlike the one shared by the open-source software movement. Although many times these journalistic outlets find themselves competing for the same story, the tools and knowledge required for reporting infrastructure, web development and newsroom workflow tend to be shared across organizations. The wheel does not have to reinvented every time. One open-sourced census map, for example, can help the next newsroom build a better one.

As Peter Aldhous, a data journalist at BuzzFeed News told Storybench: “We can stand on the shoulders of great developers and programmers. That’s a really nice thing about opensource tools.”

As much as this spirit enables information sharing between newsrooms, it also allows individual journalists like Aldhous to set up a code base where upon they can layer new modifications to produce multiple stories and iterations without starting from scratch.

At conferences such as those held by NICAR and SRCCON, specialized workshops held around the world, and websites such as Source, from the Knight-Mozilla OpenNews project, Nieman Journalism Lab and Storybench, leading digital journalists come together and openly share best practices, step-by-step instructions for building news projects and freely available repositories of the latest tools used to build digital storytelling projects, news apps and newsroom tools.

At conferences such as those held by NICAR and SRCCON, specialized workshops held around the world, and websites such as Source, from the Knight-Mozilla OpenNews project, Nieman Journalism Lab and Storybench, leading digital journalists come together and openly share best practices, step-by-step instructions for building news projects and freely available repositories of the latest tools used to build digital storytelling projects, news apps and newsroom tools.

Github, an online repository system for software and web code, has revolutionized the way these people share knowledge and collaborate, in spite of the rivalries their newsrooms may have had. The altruistic and collaborative spirit inherent in this open-source digital journalism community is exemplified in some ways by the very willingness of interviewees to share code and tools with Storybench, which serves as a conduit and forum for connecting with the wider community.

Seattle Times’ Oso landslide interactive

Examples include the sharing of code from The Guardian’s real-time interactive on primary election results, the Wall Street Journal’s “The Unraveling of Tom Hayes,” and the Seattle Times’ Oso landslide interactive.

Among the most revealing and characteristic examples of newsroom generosity on Storybench have been the tutorials voluntarily written by the Wall Street Journal’s Roger Kenny on three-dimensional data visualization and by George LeVines on branding and installing Chartbuilder, an open-source graphing tool itself.

One shining example of open-sourced code libraries and collaboration between newsrooms is the sharing and iterations of data-driven documents, or D3, which not only visualize data, but can also analyze and manipulate it. D3 is one of the most versatile script libraries employed by newsrooms. Unlike visualization software like Tableau, D3 is transparent and accessible through a web browser’s document object model (DOM), allowing for simple manipulation, modification and debugging. Newsroom designers and developers are sharing D3 code and best practices.

“A little D3 goes a long way,” Jeremy Scott Diamond, a developer with Bloomberg News, told Storybench editors, extolling the versatility of the JavaScript library.

Coupled with scalable vector graphics, or SVG, digital newsrooms have made D3 the gold standard for visualizing linear, non-linear and multi-dimensional data using hundreds of D3 visualization packages. D3’s open-source nature has allowed journalists, developers, designers and researchers to contribute code and expand the number of packages available. (See D3js.org for examples.) Other JavaScript visualization libraries used in newsrooms include Highcharts, Leaflet, Sigma, NVD3 and Gephi.

“We can stand on the shoulders of great developers and programmers. That’s a really nice thing about opensource tools.” – Buzzfeed News’s Peter Aldhous

While many programming languages tend to become obsolete in the space of a few years, for students and journalists wanting to become adept at custom data visualization in the digital newsroom, D3 has evolved into a kind of gold standard.

There are of course running discussions about whether or not all journalists should learn to code. Setting aside the desirability or need for uniform training, it is certainly useful to know that training in JavaScript libraries, specifically D3, will serve journalists who want to visualize data for their stories well into the future.

Mobile-focused ideation

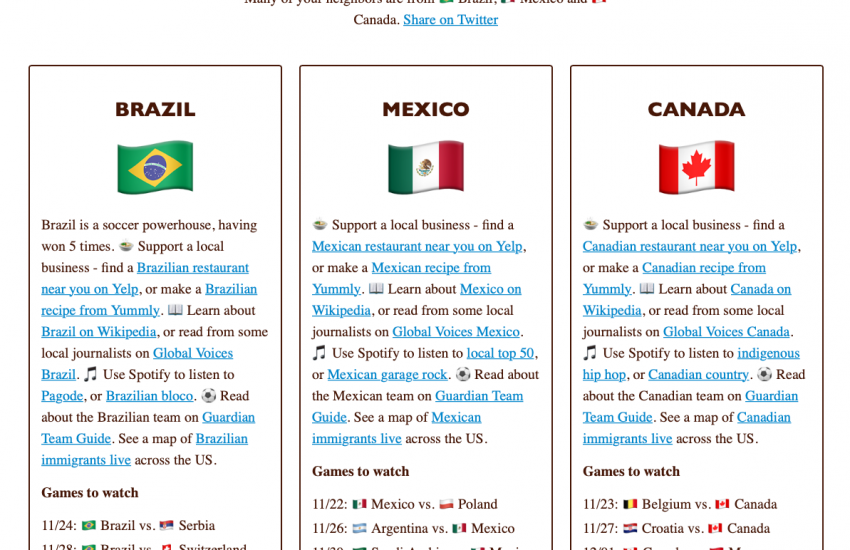

A final recurring theme, and one that likely portends the future in this space, is the impact of mobile devices at a level more fundamental than just customization and re-purposing of news content. Design-centered thinking is inherent in mobile-centered design.

As news audiences are shifting to mobile devices, so too are design standards. In fact, the Pew Research Center’s “State of the News Media 2016” report surveyed 40 digital-native news sites and found that for 38 of them, more visitors came from mobile devices than from desktops.

With more readers accessing news sites from tablets and cellphones, mobile-focused and responsive design have become a priority in the digital newsroom. Likewise, collaboration between newsroom developers and the editorial department, where mobile design is considered in tandem with coverage, is beginning to flourish.

Storybench interviews have revealed several instances where mobile design frames the journalistic process itself.

“Mobile was the driving idea behind [the story],” said New York Times designer Matt Ruby, who helped plan – and shared editorial control over – reporter Emily Rueb’s mobile-first, flipbook-style article on New York City’s tapwater. Many other media producers have also described how the philosophy of “mobile-first” is redefining the production of journalism, and reshaping the way news producers think about stories. This represents a new and important phase in the industry’s development and one that scholars have yet to analyze fully.

“Mobile was the driving idea behind [the story],” said New York Times designer Matt Ruby, who helped plan – and shared editorial control over – reporter Emily Rueb’s mobile-first, flipbook-style article on New York City’s tapwater. Many other media producers have also described how the philosophy of “mobile-first” is redefining the production of journalism, and reshaping the way news producers think about stories. This represents a new and important phase in the industry’s development and one that scholars have yet to analyze fully.

For example, Oscar Westlund’s “Model of Journalism” in a mobile context puts forward a multidimensional schema, running from repurposing to customization and humans to technology. To this we might add the dimension of ideation, a further iteration of mobile news practice whereby stories are conceived of and executed as what might be called “mobile native.”

There has been a fair amount of attention to what has been called “mojo,” or mobile journalism, news practices, but this new conceptual turn in newsrooms demands more research, particularly relating to how new functionality and affordances are driving the editorial process in a more fundamental way.

It is worth noting here that, despite worries that mobile will diminish the range of stories, design constraints may actually represent strengths for journalism, whereby screen size, touch and swipe functions, faster load times and improved browser technology can be leveraged to frame digital storytelling in refreshing new ways. Newsrooms are employing nimble web design frameworks, lightweight “minified” code libraries, and versatile design markup languages like CSS and SASS to more effectively display stories on mobile.

Conclusions

Journalism in the digital age has always presented a conundrum: The industry has struggled to adapt to secular trends that are eroding its most fundamental business model; and yet the same technological innovations that engendered catastrophic revenue declines have led to startling advances in the actual day-to-day practice of journalism. Unfortunately, our focus on the former has often eclipsed our understanding of the latter. This effect was greatly compounded by the sheer plurality of new platforms, programming languages, tools and approaches that have characterized the last ten years.

This effect was greatly compounded by the sheer plurality of new platforms, programming languages, tools, and approaches that have characterized the last ten years. What our source material—the Storybench interviews—reveals is that all the tumult produced by both economic disruption and rapid technological change is now crystallizing into a new set of “standard operating procedures,” three of which we detail in the paper above. Some of these—the rise of an open source ethos, for instance—are more philosophical and cultural in nature. Others, like the adaptation of editorial products for mobile consumption, are more pragmatic and technological in nature. Either way the bottom line is good news for those who work in journalism, as well as those who would study it – the inchoate has given rise to discernible form.

The three categories, or areas of emphasis, mapped out here – team-based collaboration; open-source mentality and operations;; and mobile-driven ideation – are intended as a practical guide for understanding an evolving field and where it may be heading. The synthesis presented here is intended, to some extent, to demystify and clarify. Of course, the categories do not encompass all dimensions of computational/data journalism or related visualization/interactive development as practiced in professional newsrooms. But seeing these areas of emphasis more clearly and distinctly is important, as certain routines and workflows in this field differ substantially from those embedded in traditional reporting and editing practice.

Further research might look more systematically at the data cleaning and statistical analysis-related aspects of contemporary journalism, where tools such as the programming languages R and Python, Excel, and OpenRefine might feature more prominently. Doig and others have articulated the new possibilities for doing “social science on deadline”[23]; the ways in which this is being attempted analytically in practice, from the perspective of routines and workflows, would be useful. Another promising research opportunity might examine how various institutions of journalism education have adapted to the same emerging practices we identify above. This is of special interest to us, as Storybench itself is an editorial outlet created by the faculty and students within the Media Innovation program of Northeastern University’s School of Journalism. One goal of the Media Innovation program was to transform traditional journalistic pedagogy to the rapid changes occurring in the professional sphere; another was to create venues, like Storybench, through which those changes might be studied. While much work remains, we are encouraged by early steps.

What becomes clear in speaking with news producers across the current landscape is that this emerging group within the journalism community frequently builds on the work of others, from the sharing of code and the complex workflow of multi-person news teams to the collective improvement of design elements and tools. For journalism professionals trying to manage and innovate at the intersection of design and data, as well for teachers and students engaged in preparing for professional success, it is vital to acknowledge and grasp the networked nature of work done in this space – and the core patterns that may increasingly characterize such journalistic work in the future.

For generations, journalists working in newsrooms, particularly at print outlets, have often operated in relative isolation, mostly reporting alone and submitting copy to perhaps one editor. Broadcast outlets have, by contrast, often required extensive teams of reporters, editors, producers, and technicians to build a story. In creating online news products through teamwork, the digital newsroom of today may in some respects look increasingly like the broadcast model. However, what may ultimately distinguish this new paradigm is the degree to which open-source code and cross-institutional sharing and learning permeate the storytelling process.

Funding

This research was based on a project funded by the Knight Foundation.