What can data visualization learn from feminism?

It’s about time to infuse feminism into data science and visualization. At least, that’s what Emerson data visualization and civic tech professor Catherine D’Ignazio says based on her research into what an intersectional feminist perspective on data could look like.

“We’re in this moment when big data and visualization are being heralded as powerful new ways of producing knowledge about the world,” D’Ignazio said at a recent talk hosted by the Northeastern University Visualization Consortium. “So whenever anything has lots of power and is valued very widely by society, we just want to interrogate that a little more and say ‘Is it being valued equally?’ and ‘Is it benefitting all people equally?’”

She and her research partner found that the field has major problems with inequality, inclusion and quantification. Those who have the resources to collect, store, maintain, analyze and derive insight from large amounts of data are generally corporations, governments and universities. This creates an imbalance between who data is about and who has access to that data.

There is an imbalance between who data is about and who has access to that data.

D’Ignazio says this issue is compounded by the fact that women and people of color are underrepresented in data science and technical fields in general, a trend that is worsening. She also highlights skewed quantity and quality of data that is collected about various groups of people. For instance, there are very detailed datasets on gross domestic product and prostate function, but very poor datasets on hate crimes and the composition breast milk.

“Even when there is institutional and political will to collect data, data on sensitive topics — such as domestic violence, war crimes, sexual assault — is often highly flawed because there is powerful incentives for institutions and individuals not to report, not to collect, not to come forward,” she said.

So how do we take a feminist perspective on the design of visualizations? D’Ignazio cited six points that might bring us there.

Examine power and aspire to empowerment

A big part of instilling feminism in data studies is to think critically about who makes visualizations and reflect on what strategies for teaching and engagement could broaden the data community.

“Data viz is uniquely suited, I think, to addressing the intersectional and structural forces that shape our current power imbalances,” D’Ignazio said. “But the key thing is that it has to be in the hands of people who are not blind to those power imbalances. It has to be in the hands of the people who see those and see those worthy of mapping.”

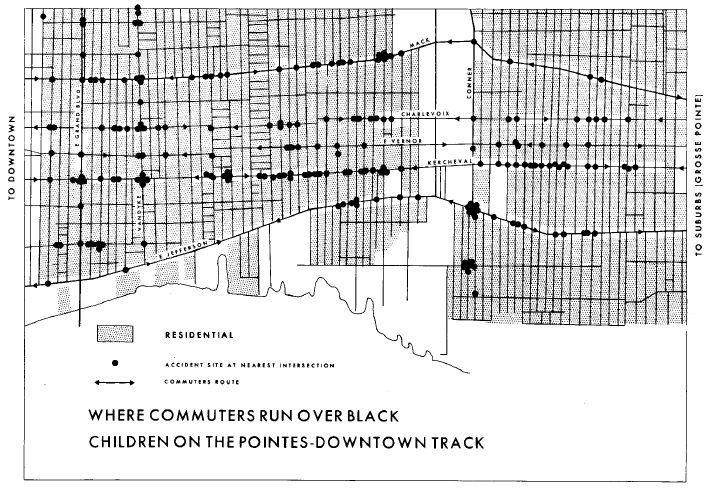

When a group of white male researchers partnered with poor, inner-city black youth in Michigan to work on data visualization, for instance, the result was a revealing map of where commuters run over black children — a topic that may not have been looked at more closely without the collaboration.

“This idea of examining power means basically just tuning your subjects and form of data visualization to explicitly focus on systems of inequality,” D’Ignazio said. “This idea of examining power raises this idea of perspective — so data visualization by whom, for whom, with whose data and with whose values?”

Embrace pluralism

“Objectivity is stronger when there are multiple perspectives at the table,” D’Ignazio said to launch this bullet point in her list. Every person’s view is a partial view, so an important first step is to minimize the focus on organized visualizations and welcome multiple perspectives in the design process.

She pointed to the anti-eviction mapping project in San Francisco, an ongoing project mapping the housing crisis in the Bay city. With no singular ‘big viewpoint’ visualization and more than 80 visualizations nested on its homepage, the website is messy. But that is part of the point.

“Their website is not only about the output,” D’Ignazio said, “but it’s also about the collective organizing and the movement building and teaching people along the way in their community about how to collect data, how to produce maps and how to use those maps situated in that context to advocate for tenants’ rights and other things like that.”

Consider context

The idea of considering context means to determine data’s context even when it’s not provided — a practice that is important to getting any story right.

“There’s this idea that with enough data, the data can speak for itself,” D’Ignazio explained. “But data doesn’t speak for itself. It can’t. And it’s important that it doesn’t speak for itself, in particular with data that relates to people who are not members of the dominant group.”

For example, data about sexual assault on college campuses collected through the Clery Act, which mandates colleges publicly report annual campus crime statistics, would indicate that Williams College in Massachusetts has rampant sexual assault problems while Boston University has relatively few cases.

“The truth is actually probably closer to the opposite of that statement, but you can’t know that without understanding the context of the data,” D’Ignazio says, explaining that when students investigated the phenomenon they found some schools had higher rates of reported sexual assault because they had more resources devoting to enabling survivors to come forward.

Legitimize affect and embodiment

Though traditional wisdom pertaining to data visualization emphasizes simplicity and condemns embellishments, feminist theory and contemporary visualization research shows that this minimalist approach is “basically just wrong,” D’Ignazio said.

“Humans beings are not a pair of disembodied eyes attached to a brain, but we’re actually these bodies and we think and we feel and we like to laugh, we like to be surprised by things, we like to listen to stories, we like to be affected by the world.”

So, by expanding the idea of what counts as data visualization and what senses those visualizations tune into, the data field can have a broader impact with more visceral and memorable messages.

Represent uncertainty

“Any given visualization does not represent the whole picture.”

The key point D’Ignazio makes here is that the data community needs better methods for showing the limitations of knowledge and representing uncertainty. Relating to feminism, this circles back to the idea that knowledge is partial, so any given visualization does not represent the whole picture.

“Our current conventions of visualization work against showing uncertainty,” she said. “Things like clean lines and shapes reinforce this idea that data visualization is always true.” So, a feminist approach to data visualization looks at ways to make people feel the uncertainty, whether through using sketched lines instead of clean lines or movement and animation to show different scenarios.

Make the work visible

Finally, D’Ignazio said that the labor of collecting, cleaning, curating and storing data, as well as analyzing and producing data visualizations, is often rendered invisible. Brainstorming ways to make this labor visible is essential for making it equally accessible to the public.

A feminism-driven approach to data viz is especially important now considering the massive power the field has. Data looks true, it looks whole, it looks scientific and it contributes to an appearance of neutrality, D’Ignazio said. She cited feminist researcher Donna Haraway, who characterized this power as “the god trick,” or seeing everything from no perspective: Data is “the view from nowhere.”

But D’Ignazio cautioned that this view is dangerous: “We have to remember that the view from nowhere is always a view from somewhere, and it’s usually the view from the body that’s regarded as the default.”

Just when I think I can’t love Storybench more than I already do, you go and give a Donna Harraway shout-out in an article, and behold: I do!

As we pursue understanding truth with data, we must remember, “Objectivity is stronger when there are multiple perspectives at the table,” as D’Ignazio said. Thank you for this article.