How The New York Times planned its digital coverage of Europe’s refugee crisis

“Even if Denmark was made of gold, I would not want to stay here, ever.” That’s what Farid Majid, a refugee fleeing the war in Syria, told The New York Times’s Anemona Hartocollis after his family was detained by Danish police for trying to cross from Germany. Majid is one of tens of thousands of refugees pushing through Europe as they flee unrest in the Middle East, Afghanistan and Africa.

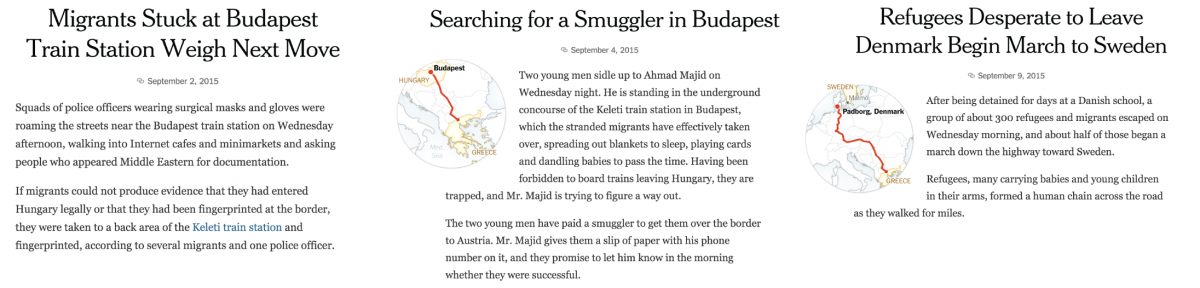

To document the journey of this massive movement of migrants and refugees and the roadblocks and setbacks they are encountering along their way, The New York Times’s international desk devised a digital strategy. It features ongoing short stories in the form of field notes from an embedded reporter, photographers and a videographer, as well as a coordinated social media strategy to broadcast their work. Storybench spoke with Hanna Ingber, an assistant editor on the international desk at The New York Times, who helped coordinate the effort.

Tell us about this project. How was it pitched?

We’re always thinking about how we can use these tools to tell a good story and do a story justice. With the migrants story, the desk had decided that we really wanted to tell the journey of these migrants and capture the movement and the difficulties and the little details of how they go border-to-border in a way that felt immersive and felt like we were embedded with the migrants.

How long has Anemona Hartocollis been following the migrant story?

Anemona Hartocollis has been in Greece since before this project began a few weeks ago. She and [a series of alternating] photographers started at the Greek border and literally day after day, she and a photographer, Sergey Ponomarev and then Mauricio Lima, and a videographer, Nabih Bulos, were following these families struggling to figure out how to get across the next border and get across the next country, which papers need to be stamped, when they should wait and be cautious and when they should run through. Anemona is witnessing agonizing decisions like “Should I hire a smuggler or use public transportation?”

Follow @anemonanyc for tweets from train station in Budapest where authorities are refusing to allow refugees thru https://t.co/gtQFmNrxvb

— Hanna Ingber (@HannaIngber) September 2, 2015

Tell me about the kind of stories she’s getting.

What’s unique about it is that they have been traveling with this group for a long time. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”explains @HannaIngber”]They are not helicoptering in to tell this story.[/inlinetweet] They’re able to show what’s happening in a very immediate way and in a very personal way. She’s mostly focused on the journey but she’s found a family of 14 refugees that she’s been following. We’ve really gotten to know this family, learning about the really hard decisions that they’re making every step of the way. The details are pretty special. She wrote a post about these Iraqi and Syrian young men now in Budapest that are middle class young guys, a law student and a dental student, and they’re horrified that they can’t get out and that they have to sleep on concrete and that they have no choice but to live in these terrible conditions. They feel like “this is not us.”

At one point, Anemona was literally camped out in the field with refugees who were trying to cross border from Serbia to Hungary… and that’s where it was really difficult. There were helicopters overhead, police flashing lights, babies crying, barbed wire fences and she’s there. She and a videographer, Nabih Bulos, caught police officers spraying an irritant at refugees trying to cross.

What are your day-to-day interactions with Anemona like?

Like any project, at first it takes a little time to figure out how it’s going to work. Very quickly Anemona figured out a great tone for the project, figured out characters that she wanted to follow, themes that she wanted to touch on. She’s done a really amazing job. She’s definitely in touch with me and other editors throughout the project. But we’re really only a sounding board. She’s the one figuring out what should be the stories.

How is a digital project like this edited at The New York Times? And does it go to print?

The stories are edited by me or another international desk editor. Step two is copy desk. Towards the end of the trip, we ran a series of the posts on the International dress page of a Sunday paper.

Now it's official. #Hungary has sealed all illegal crossings to #Europe along its #border. #refugees pic.twitter.com/FSITK3Qnie

— Sergey Ponomarev (@SergeyPonomarev) September 14, 2015

What have you learned about marketing this kind of reporter’s notebook to readers?

One of the things we’ve learned is that it doesn’t work as well to sell the “big idea” like “here’s our Reporter’s Notebook on migrants in Europe.” Instead, here is this really gripping post about Hungarian police officers spraying a family including young children with something that burns their eyes in the middle of the night. Or here’s a mother who is desperately going from country to country trying to get to a doctor for her very sick child. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @HannaIngber”]Each story needs to stand alone. We sell each one.[/inlinetweet]

Tell me about your social media strategy with this story.

We’ve been using social to promote the stories. When we write a headline we’re thinking about social. A lot of the time we’re thinking about what type of headline we need to write so that people can see and understand what they’re clicking. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @HannaIngber”]When we’re thinking about search we want proper nouns in our headlines.[/inlinetweet] On social, we want proper nouns so they know where we’re talking about. The reporter’s notebook is made up of stories that have their own URL and own headline. We can’t just assume that the reader knows that The New York Times has been embedded with this group of migrants. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @HannaIngber”]We have to assume that a reader is coming to us for the first time[/inlinetweet]. So we have to orient and situate the reader in the story at the moment.

How Europe is closing its back doors, explained in graphics: http://t.co/N1S8SrKeEE pic.twitter.com/QiAodgZq8r

— New York Times World (@nytimesworld) September 16, 2015

Tell me more about that, about digital strategies to grab readers.

When we go to Twitter or Facebook or our homepage editors, we do it when we have a single really good post. Sometimes we say “follow along” but we’ve found what’s often successful is selling the nuggets. It can have a great video with it or a graphic. And it is its own little story. Also, Anemona has a Twitter feed and Sergey Ponomarev has Instagram.

Refugees carry babies on march through #Denmark to Swedish border. They have walked 25k so far on highway. pic.twitter.com/91Z1yEzPW0

— Anemona Hartocollis (@anemonanyc) September 9, 2015

Tell me about your background and how it’s helped your work at The New York Times.

I worked at the Huffington Post and started their world section. Then I worked in India for GlobalPost. I’ve always been interested in international news and journalism. We were thinking about using readers to better to tell our story at Huffington Post. In India, I was using Twitter to really connect with readers in India and the U.S. and abroad and using Twitter to tell stories. I very quickly realized how [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @HannaIngber”]you can do a really interesting, immediate form of storytelling on Twitter[/inlinetweet]. Gripping and compelling. Even before you publish a story. When I came to The Times I originally worked on the social media desk but now I’m with the international desk using social to tell stories and gathering information and connecting with reading on those platforms. Then we try to use what we’ve found in smart ways.

What makes this story ripe for this kind of reporting format?

The one other story that we have covered in this way was the pope’s trip to Latin America. That’s the first story that the international desk used this format. That worked well because we had a very clear journey. There were small stories that Jim Yardley, who takes great photos by the way, could tell along the way. A big thing we’ve noticed is that this works well when there is one big story line but then within that story line there are individual posts that make sense to standalone. A big reason the migrant story is working so well is that the story itself is such a compelling story. It’s very dramatic. It’s very gripping and it’s happening right now.