How one VR experience explores the frightening and ebullient world of bipolar disorder

Manic is a virtual reality experience that explores the beautiful, chaotic, frightening and ebullient world of those with bipolar disorder. It follows the thoughts of creator Kalina Bertin‘s siblings, Felicia and François, through the voicemails they’ve left her as they undergo cycling states of mania, psychosis and depression.

Storybench spoke with Bertin about the virtual reality experience.

Have you done any work in the past regarding mental health?

Yeah, actually Manic VR is an accompanying piece to my documentary film called Manic, which took me four years to make. At the time, when we were putting together the budget for Manic, the government was really trying to stimulate a virtual reality experience production and digital media. So we had to present a VR component to be able to raise the budget. I really focused on the film and when the film was starting to get close [to being completed], I had to start thinking about the VR.

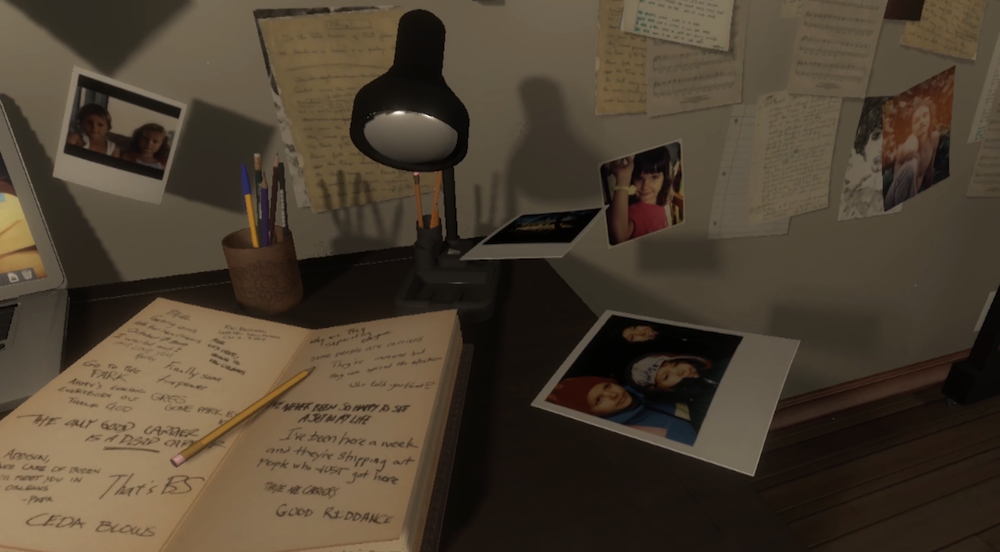

When I was editing the film, I had used some voicemails that my siblings had left me that were very, very compelling, but not all of them fit in, and I was left with some really beautiful ones. I was thinking “Okay, what if those voicemails could become the backbone of the experience.” And when I was making the documentary, I was frustrated because I was stuck with all this real-life footage and I wanted to delve into my siblings’ heads and try to enter their world, to understand what they were going through from inside. I thought VR could be an interesting way to attempt to illustrate their world; the voicemails became the backbone. Collaborating and working with them, we tried to depict their inner landscape.

I thought the voicemails were an ingenious way to tell this story; it felt very natural. Was there a story that existed before the voicemails or did the voicemails create the story?

When you’re in a state of mania, you become very verbal and you really feel the need to talk. My siblings would call me—and this is when I was making the film, so sometimes I’d be in Thailand or Hawaii shooting, so I couldn’t always answer my phone—so they’d leave me these messages, and I was like, “Gosh, these messages are so interesting,” so I started keeping a record of them—recording them, recording them. My sister started saying, “Okay, when I call you, don’t answer, because I really like leaving those voicemails on your answering machine.” It was like my voicemail became their personal diary to capture their experiences, and they can go back and listen to that, and it would give them an opportunity to look back on that [past] state.

What happens also when you go through mania or psychosis, sometimes you have memory loss. So some things that they didn’t even remember saying… It’s kind of them documenting all that and investigating their own state in a way. That’s how I had all that footage; it was going through maybe like two or three hours of voicemails.

It seems like mutual thing; it’s helpful for them to leave these messages, and, in return, you were able to create such a beautiful piece for people to experience from their voicemails. It’s almost like a mirror, in a way.

Absolutely, yeah. I was really trying to understand what bipolar disorder was, so I did a lot of research. I felt like a lot of the films or experiences that tackled that condition were all very similar, so I wanted to do something creative and different… and something in which my siblings would feel that they were in power and for them to be able to tell their story. You feel so much like a victim when you are going through those moments, but to give [my siblings] that creative power, was really beautiful for them.

They would see different iterations of the project, and then last week I showed them the final version, and they were just so blown away. They felt that they could get something beautiful out of those really hard experiences. It was kind of therapeutic for that too.

I feel like a lot of documentary films and media centering on metal health either fall into romanticizing it or being uncomfortably serious and negative. Manic felt separate from those, it made a new space to take everything seriously yet not romanticize bipolar disorder.

It’s a really fine line between glamorizing it or overdramatizing it. It was really tricky. We wanted to be careful with that.

On a different note, how did you go about the art design? The scenes you built felt so lifelike and personal. What was your artistic process like?

I created a mood board with the style I wanted, a bunch of different elements that I would paste onto a document. Then, we gave that a concept artist, and based on all of those details—details of the bath, details of the trees, details of the leaves, details of the colors and textures—he would draw a world. I would approve, or disapprove, give feedback, show it to my siblings. I’d ask [my siblings], “Look at this thing. Does it feel accurate? Yes? No?”

Once that was locked on paper, we gave it to a 3D modeler and he embodied it, brought it to life through 3D software. Then, it was programming all the effects [and finalizing the piece].

The final piece shown at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest was completely breathtaking. I especially loved Manic’s use of haptic feedback with your hands with the VR controllers.

The haptic feedback happens twice. First, when you’re in the bedroom and—did you hit the bubbles [and hear the musical notes they make when you pop them]?

Oh my god, yes.

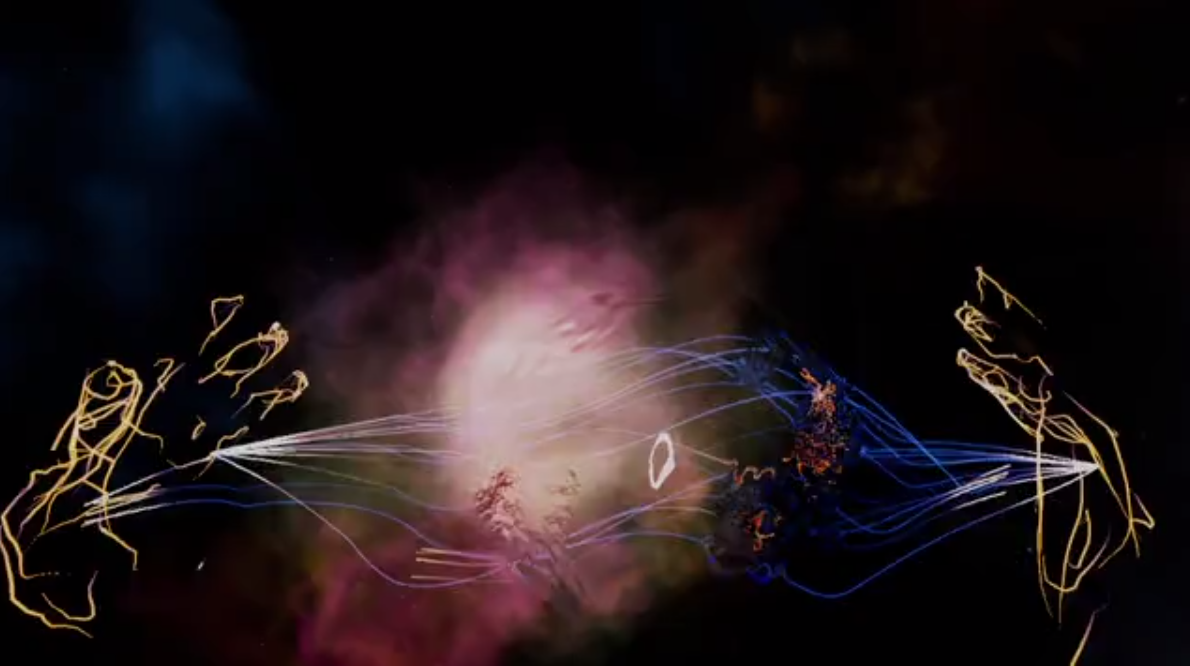

And then again in the galaxy [where you hold streams of light between your hands]. For me, the haptic feedback was important because interaction [in Manic] is engaged at certain moments, but not always. We need [to be able to establish] that as a key moment. The haptic feedback induces an electric energy buzz, which very much goes [hand in hand] with the states of mania and hypomania. I thought it was really appropriate for that too.

At first, the feedback unsettled me because I wasn’t expecting it and, like you said, it makes you feel kind of an electric sensation. But then, in the galaxy scene, it was so appropriate and beautiful. I was wondering how you came up with that space metaphor, where it came from.

It came from my sister; she’s saying “These galaxies, these ethers…” When she was in a state of mania, and crossing over into the psychosis, the cosmos became a recurring theme. She was obsessed with the cosmos. She felt this connection to the sky, to the moon, to the stars. She felt like there was something very spiritual and godly inhabiting her.

I wanted to do a chapter in which the user could be enveloped in that space. There was something very exuberant about those nebulas—it’s all gassy textures and the stars. I thought that visually represented what my sister had told me about that state.

VR is such a great medium for all those visuals around you. The way the user is “un-bodied” except for the scenes involving haptic feedback in the hands was a great metaphor for the user being a witness—a visitor—to your sibling’s stories.

Yes, a visitor. When I was pitching the project, people would ask, “Okay, but who am I in this experience?” You’re not my sister or my brother; I just want the user to be a visitor, because it feels more respectful. It doesn’t feel like we are putting you in a very awkward position where you’re going through a manic episode, because we can’t do that. That’s stupid and irrelevant. We can’t pretend we are putting anybody through a manic episode, but we can invite people to be visitors in this very complex world. If you are anyone in this experience, it’s like you are me listening to these voicemails and trying to imagine what my siblings are going through.

What kind of responsibility, if any, do you think media makers have when making pieces about mental health and mental illness? Is there any stigma against making these works?

Oh yeah. I found it very nerve wracking, because when I was making my documentary film I did everything on my own. I shot on my own, I did the sound. I worked with an editor, but it was very small team. For something technical like this, you have to work with more people, and it was kind of terrifying. I wasn’t the one who was generating all that; I had to explain to somebody what I wanted. It was a bit scary, to let go of the control a little, but you must in these creative processes.

“If the story is compelling and they are well guided, they will follow your lead.”

I’m really happy with what they did in the end, but because of that very important responsibility that I felt, I wanted to make sure that my siblings were comfortable with what we were portraying. It’s their story, as much as it is of anyone who was on the team. We are all sort of erased and behind the scenes, but they are the ones at the forefront. For me, exercising that responsibility was showing different versions to my siblings, getting feedback, making sure that they liked it and that it made sense to them. I thought maybe [Manic] could be useful for other people who have bipolar disorder to go through this experience and relate. Everyone experiences bipolar disorder differently, but there are these recurring symptoms.

If this could be used as a tool for somebody who has bipolar disorder, to tell their loved ones or their parents, “Put on the headset [and watch this video], and we will talk about it after.” There are some things that [everyone] can relate to. We did a family viewing, and my sister has a ten year old daughter. When she came out of the experience, she sat next to her mother—my sister—and she told her, “Ohhh, so that’s what it is like to be in mania.” She had seen her mother, and she couldn’t understand or relate to what her mother was going through when her mother was talking about God or going through all this delusion. Being able to experience this in virtual reality broadened her comprehension of what her mother was going through.

Was there anything surprising about making a VR piece, since you mostly have experience in documentary filmmaking?

When I first met with the creative studio who I worked with for this, I asked them “Okay, so what’s the workflow?” because it was my first VR experience. They said, “Well… we reinvent the workflow for every project.” And that [threw me off-guard] because I had to work with this new medium and invent the workflow, so that was a bit scary. Each workflow is adapted based on the project, which actually is a great thing because every process is unique.

In a sense, you can relate if you come from documentary, because it requires a lot of iteration. You have an initial idea and you test it out, but then it changes—you have to adapt it. In documentary, you set out to capture a story, but then reality has its own plan. And sometimes it works out better! However, what was really important for VR was to test out the ideas, because sometimes things were great on the script, but when you put it in VR, it didn’t work at all. You had to iterate and iterate and iterate. Designing interactions was very tricky, because you want the interactions to feed into the story. You don’t want it to be a distraction. For us, because the story was so much carried on by my siblings’ voices, we had to be careful to balance it out.

Did you experience any difficulty in using VR, especially in regards to controlling the story/message or directing the user’s attention?

What I love about VR is that storytelling is very much layered. You have the first line that hopefully 90 percent of the people will get, then the second story line which maybe 80 percent will get, and the third one, maybe 70 percent… You have all the layers, and the core of your message must be the obvious one, but you can still use different tools to direct the view of the user. Sound, light… there are all sorts of ways, so you still have to direct, it’s not like the user can do whatever [they want]. If the story is compelling and they are well guided, they will follow your lead.

___

Check out Kalina’s documentary Manic, the companion piece to her VR experience.