Jan Diehm of the Pudding brings human-centered design to storytelling

At first glance, crossword puzzles, “gayborhoods,” and the fashion industry don’t have much in common, but a look through journalist-engineer Jan Diehm’s portfolio at The Pudding reveals that there are often important stories beneath the surface waiting to be told with a new kind of data and design-informed storytelling.

It certainly wouldn’t come as a surprise to any working journalist that today’s news cycle, whether it be in the context of U.S. politics, pop culture or social justice issues, is a restless, driving force behind what makes the front pages of longstanding news publications and the broadcasting slots on primetime television. Diehm, whose career path through journalism has led her through roles involving newspaper pagination at the Hartford Courant to data and design work at the likes of HuffPost, ABC News and CNN, said this kind of cycle confines journalists to coverage of the same types of stories.

“I wanted to have the freedom to breakdown the box,” Diehm says. “If there’s something happening every day you go into work, you’re just at the whim of things. So, you’re often reactive in what you build, whereas at The Pudding, I feel like I can be proactive, like I can decide what stories I’m most interested in, what skills I want to build and who I want to partner with on the team.”

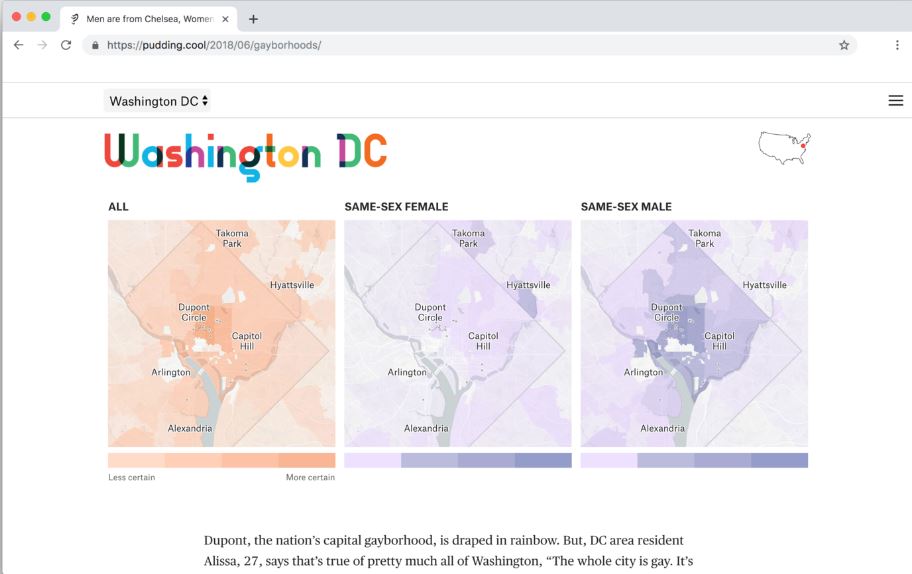

Diehm’s data and design-driven projects cover a wide spectrum of issues ranging from lighthearted analyses of Kidz Bop covers and how people express laughter online, to some of the more reflective, human-centered stories that spring from many socioeconomic, race, gender and sexuality-related trends. Diehm has a passion for pursuing the stories that lie beneath the data’s surface: Stories of representation and inclusivity from crossword puzzles to politics; colorism in the fashion industry; and societal circumstances behind the makeup of today’s “gayborhoods”.

“I think the stories that I’m most proud of are the ones that take something at the surface level and that’s in your day-to-day life or pop culture and then try to reveal a deeper truth in them,” she said. “I feel that’s like meeting people where they are.”

Storybench spoke with Diehm on how her projects at The Pudding are different from previous experiences and the kinds of stories she wishes to tell in the future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How much of the content you work on comes from your pitches? What would you say is the ratio between that and projects where The Pudding comes to you and says, “Hey, Jan, we want you to work on this with so and so?”

I’d say the majority of the time, it’s stuff you’ve pitched yourself. Maybe 70 percent-ish. It varies between the team; I feel like I’m a little atypical in that because my work style is probably from what I picked up from newsrooms and held on to. I like to bop around between a bunch of different projects. I also naturally float in and out of projects more to make sure that the story is sound, and that we’re not putting out anything that looks super ugly. So I feel like more team members often or other team members often work on more of their own stories. But I found my sweet spot [where] I almost feel like I’m a conduit, where I don’t necessarily need to feel like they’re my stories. I want to tell whoever’s stories in the best way possible. I get the same energy in telling my stories [that I do] from telling other people’s stories.

Do you see opportunities you get at The Pudding to tell those stories in different ways than from past experiences at other newsrooms? Do you feel like you have a bit more liberty to go after what you want to tackle story-wise?

Definitely. I think that the content that we pick is a little bit more evergreen. I think it’s hard in a newsroom because, again, you’re attached to that news cycle. And there are some great investigative desks that are more long-term than these one-off projects or series. But I think that we do that work all the time. So, that’s an advantage. The other thing is, because we’re not in a legacy news org, we don’t have to adhere to the definitions of what is considered objective reporting. I think that a lot of times, and to our detriment a little bit, it’s like we’ve completely removed the human element of journalism. It’s like you have to be devoid of emotions, devoid of anything that makes you human.

Going back to the “Gayborhoods” piece, there are parts of me in that story, very clearly. And I don’t think I could do that in another place. It makes me closer to the story. It makes me care about the story more, but I don’t think it objectively alters the story in any way. Whereas at other career stops along the way, I remember when the big marriage equality stuff was happening, we were given directives, like, “Even though this is very personal, and you want to celebrate it, maybe don’t come out on social media and say anything too overly celebratory, because it could be seen as partisan.” It’s like, to me it’s not a partisan issue. It’s just — it’s a human issue. So, I think that we avoid that at The Pudding a lot, and having to grapple with that, and just putting our foot firmly on the ground and saying, “No, you can be a strong journalist, and you can be a strong human, and those two things can go together.”

Diehm’s project “Men are from Chelsea, Women are from Park Slope” visualizes residential trends among LGBTQ+ people in 15 different American cities. Credits: Squarespace/Images

Among your different design and written projects, are there any particular ones that you’re most proud of?

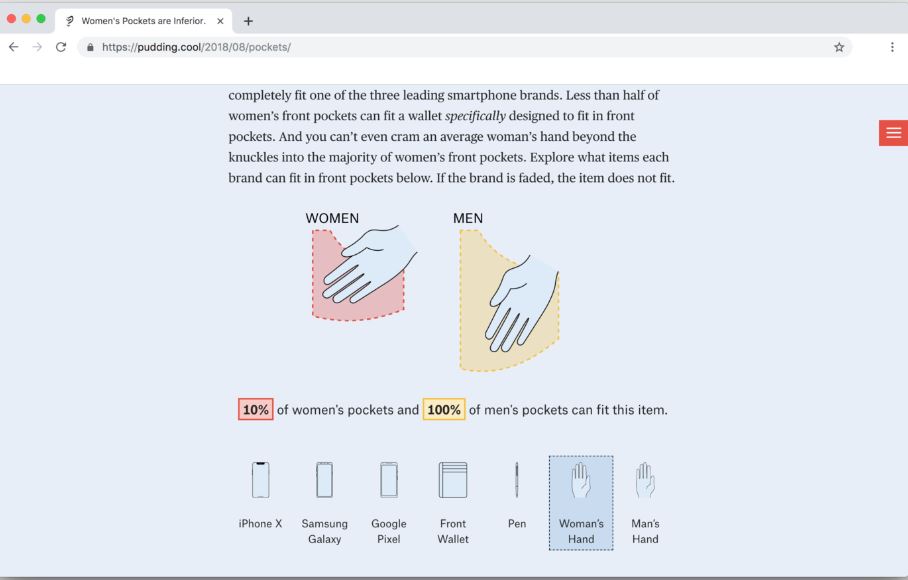

Most people don’t spend their days thinking about very serious topics. If you do, you go into a spiral — it’s hard, right? There’s so many serious things in the world, but [people] do think about what happens to them on a day-to-day basis, what they see on social media. If you can sneak some of those hard topics in underneath the surface, it’s like a spoonful of sugar, or, like a tip-of-the-iceberg type of deal. I think that the two stories that I’ve done that best capture that are one on pocket size between men and women’s jeans, because it gets at the autonomy of women’s bodies and the patriarchal system, without bashing you over the head with that and saying, “Hey, we’re going to talk about this, like really difficult, systemic, ingrained thing in society.” Instead, we’re going to talk about pocket size, which you probably experienced day-to-day.

[Another story] that I think does that in a decent way is a piece called “You Know Karen,” and that looks at the popularity of the “Karen” meme, and what other names could be Karen. I think it’s one of those questions where it’s like, “Well, what’s the male equivalent of Karen?” “Karen” has become this societal thing—everybody knows who “Karen” is. So, we tried to look at that a little bit with data. But throughout the story, it’s very clear about where this meme comes from and what it means. So again, it’s trying to give you that deeper truth, but packaged in a nice, shiny, fun package.

Do you think that this style of storytelling lands differently with audiences than the traditional, “devoid” journalistic approach?

We see so many great data pieces come out of the big two, the New York Times and the Washington Post, and I have friends on both desks, and they’re doing tremendous work. But oftentimes, because of the constraints of their [content management system], or that they need to be more restrained in design in the sense — you know, the design is getting at that objectiveness, like, they want to make everything kind of the same. I think that because we get to design things in a more whimsical way, with a more personal bent to things, it definitely has this staying power that sometimes you wouldn’t see because it relates to your personal day. It’s a lived experience that you can relate to, and I think that’s really important. People want to see themselves in stories.

“Women’s Pockets are Inferior,” which Diehm developed with her colleague Amber Thomas, looks at the differences in pocket size between pants made for women and pants made for men. Credits: Squarespace/Images

Where do you see this style of journalism and storytelling going? What kinds of stories would you like to be telling, and how would you like to be telling them in whatever the future of media looks like?

I think that the biggest thing is that we’re going to need to meet people where they are. So making sure that we stay up to date on how people are consuming news. I think that in the field of digital journalism, right now, there are two edges of the spectrum. One is the stuff that we do with The Pudding, where we want people to sit with your story a little bit — it’s longer, it has more charts, it takes more time to sit with it. The other side of it is Instagram or the TikTok or the quick satisfaction stuff. But, we know that if you can tell the story in a compelling way, people will spend time with it.