How the Palm Beach Post unearthed an opioid conspiracy with roots in Florida

Located in one of the states hardest hit by the opioid crisis, Florida’s Palm Beach Post has covered the issue from drug deals in the streets to boardroom deals at Big Pharma. For their latest series, several reporters took a comprehensive look at one pharmaceutical company that earned major profits bribing doctors to prescribe their opioid product to the masses.

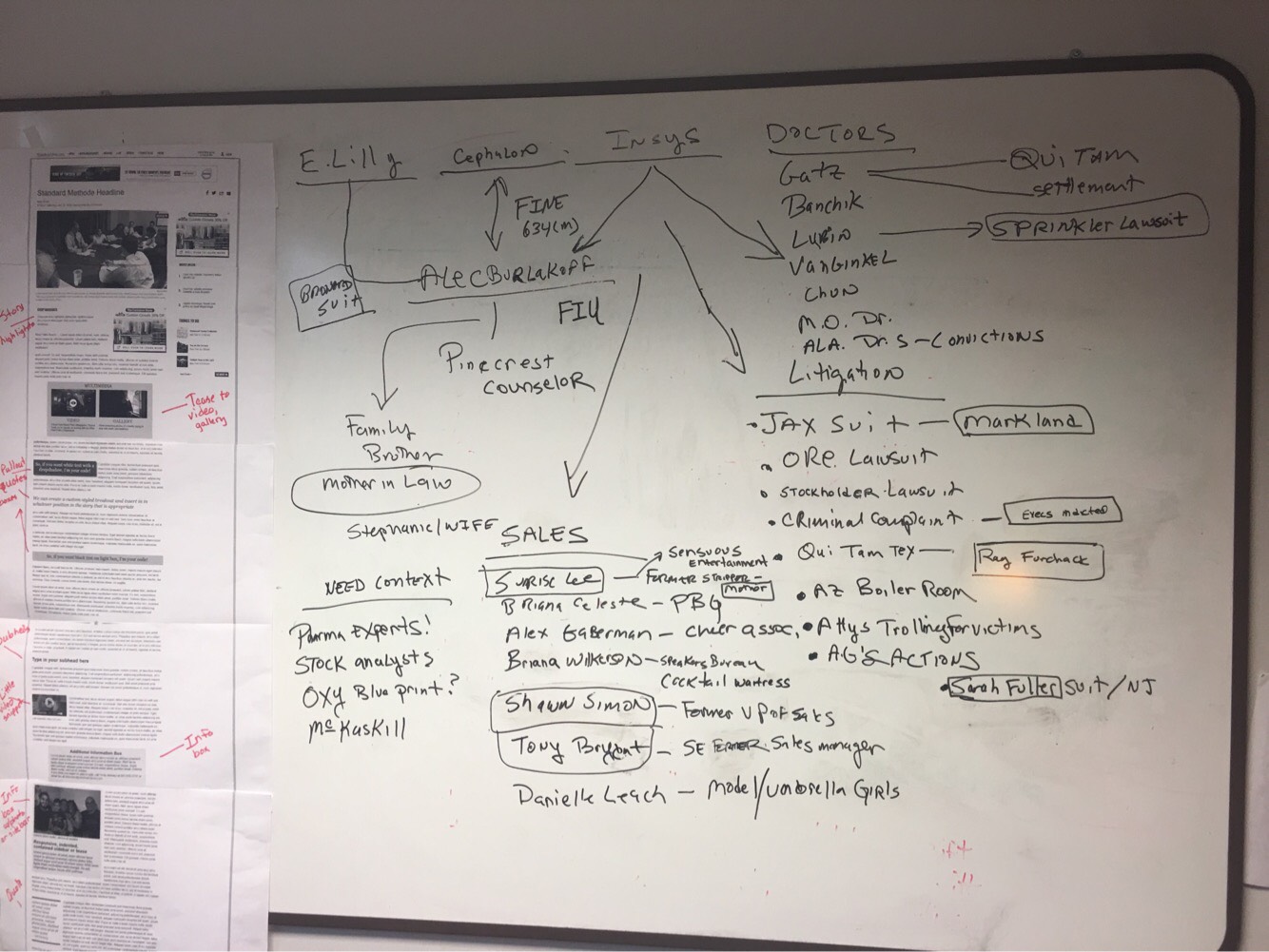

The drug in question, Subsys, a sprayable form of fentanyl, is intended for cancer patients with pain so severe no other painkillers are effective. But at Insys, a company now faced with lawsuits from patients, stockholders and governments, The Post found it was routine to bribe doctors to prescribe the medication to non-cancer patients as a default. What’s more, nearly all of the salespeople working under vice president of sales Alec Burlakoff were “extremely attractive women” who had no pharmaceutical experience.

“In this case we wanted to show how this company went rogue with no concern for the public’s well-being and their role in this crisis,” said co-writer John Pacenti, who has been a reporter for 30 years. Stories of individual lawsuits against Insys have popped up in publications across the United States but Pacenti said their story was the first to put the pieces together and expose the scope of the company’s misdeeds — and their impact.

“The thing that this story does that I don’t think other stories do on this topic,” Pacenti said, “is that it pulls it all together. It shows how this company took what was a sketchy template to begin with and just exploited it to a point that I don’t think we’ve seen in the pharmaceutical industry in the past.”

To look at the bigger picture, The Palm Beach Post reporting team had to determine how many people had potentially died from the drug. This meant Post data reporter and Northeastern graduate school alum Mike Stucka had to clean, combine and cross-check three large FDA datasets.

Sifting through government data

Stucka said his back-and-fourth between versions of FDA data—which included CSV files, an API and an unwieldy web interface—revealed an appalling surprise. The web interface, as the most likely version to be used by the public, consistently undercounted incidents involving the opioid by about 10 percent because it used the drug’s name to identify it rather than its ID number.

There were other inconsistencies in the data, as well. Stucka said there were some instances where a person was not marked as dead, but the report notes mentioned they had died. The FDA did not respond when he asked why.

“How do you draw conclusions when so many of the answers you’re looking for are blank?” he said. “Could you say that all of those cases are actually for things like back pain instead of cancer pain? No. Could you say none of them are? Probably not either.”

The team double-checked their results with Dollars for Docs, a ProPublica tool that allows users to search for data about pharmaceutical company payments to doctors. Stucka also spoke with an expert from Georgetown University, who pointed the reporting team to analyses that suggested a large portion of cases involving adverse events to drugs are never reported to the FDA.

“There is some concern over how thorough the database is just because it’s voluntary reporting and it takes a reasonable commitment of time to report a case,” Stucka said, “but the cases in there are reported by professionals like doctors or nurses. You can count on them.” Still, his team wondered if the number of deaths they reported was an undercount.

Talking to lawyers

In addition to FDA data, Pacenti weeded through thousands of pages of court documents, primarily criminal and civil lawsuits. His research brought him to FCC filings, LinkedIn profiles and repeatedly to people over the phone. Nobody wanted to talk to him because of the closed culture surrounding the pharmaceutical industry.

“I started a conversation with their lawyers,” Pacenti said. “These were months-long conversations, getting their trust, getting them to know me, not knowing if it would pay off. I’m just trying my best.”

The first time Pacenti met with one lawyer in person, the two spent half an hour chatting about personal matters rather than the story. “I developed rapport with him over months, not really expecting him to pony up his client like he did,” Pacenti said, “but that’s exactly what happened.”

The local angle

The Palm Beach Post reporters were ideally situated to take on the story because some of the scandal’s major players had local ties. Burlakoff and one of the main defendants in the federal indictment had roots in Palm Beach County; the latter was a former exotic dancer at a popular gentleman’s club in the area.

“It is very likely that the whole scandal might have been hatched here,”Pacenti said, referring to the fact that Burlakoff had worked with another pharmaceutical company in Florida. “We had this Palm Beach County angle that gave us insight into the story.”

Pacenti said one of the best parts of reporting the series was that he got to hold up experts who fight miseducation about opioids, and that readers have responded to say they are hungry for this type of investigative journalism.

“Opioids are not the best for long-term pain management, they’re not designed for that,” Pacenti said, “but right now they’re the default. The consequence is we are creating drug addicts. Hopefully with this we will be able to educate the public to that fact.”