A quick tour of the science of virtual reality

It’s teaching paraplegics to walk. It’s untangling genes. It’s showing you what it’s like to be a different race. Virtual reality is being heralded as a medium with which to change minds and convey new perspectives. But what exactly is it doing to your brain?

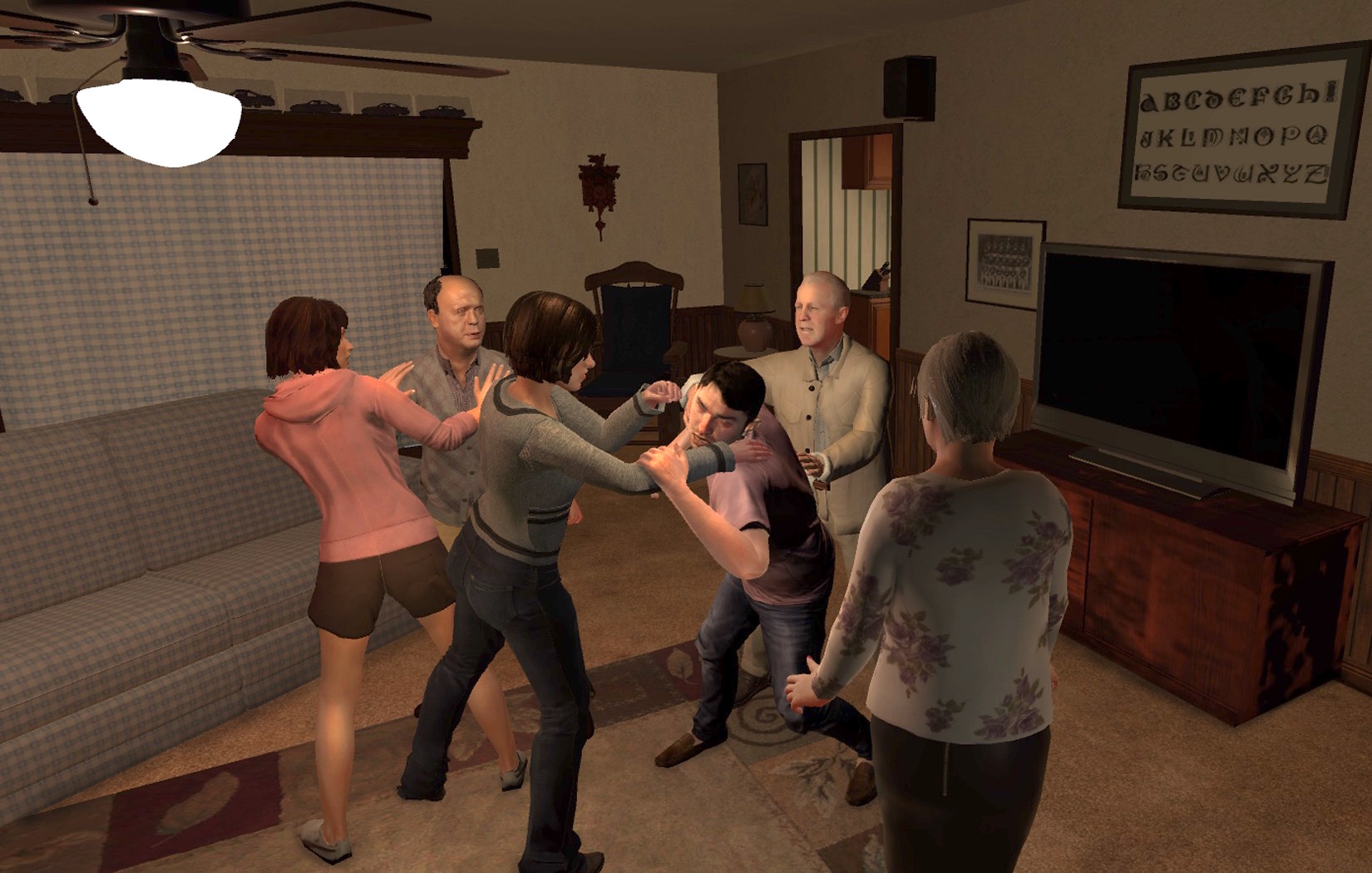

We asked Nonny de la Peña, the immersive storytelling pioneer who many have hailed the “Godmother of VR.” De La Peña created “Hunger in L.A.,” the first virtual reality experience to screen at Sundance in 2012; her intern Palmer Luckey later went on to create the Oculus Rift headset. Her empathy-laden repertoire spans stories touching on Aleppo and Trayvon Martin and most recently, “Out of Exile,” about domestic violence in the LGBTQ community. She is certain of many things in her work. But when asked about the effect virtual reality is having on the brain, she stumbled: “Well…you know, we don’t really know exactly.”

Neither does neuroscience. In 2014, UCLA professor Mayank Mehta designed a virtual reality experience for rats and zoned in on the hippocampus, the part of the brain that creates new memories and designs a spatial map of the environment. When placed in VR, half of the rats’ hippocampal neurons shut down. The ones that were active fired totally randomly, meaning, from a scientific perspective, that neurons had zero idea where the rat was. That same year, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to John O’Keefe for the discovery of place cells, which combine with grid cells to create a brain map of our surrounding area. Those cells, it seemed, would fire whether you’re wearing a VR headset or not.

“The first question in ethics is, ‘How far do we actually want to go?’ ”

After O’Keefe’s discovery, neuroscientists deemed these cells the brain’s GPS—until this year. In April, Stanford researchers Lisa Giocomo and Surya Ganguli actually looked closely at navigational neurons, and discovered that comparing the brain’s navigation system to a GPS was laughable. Our sense of place, of course, was more complex than previously thought and they struggled to even identify any particular set of existing neuron types. “We saw this big continuum,” Ganguli told Stanford News, a discovery that sends scientists studying brain navigation back to the drawing board.

But if technology halted every time scientists couldn’t figure out something about the brain, you wouldn’t be reading this article. Virtual reality disregards the unknown and continues to sprawl, spanning countless industries—medicine, education, and especially media.

“The first reaction with a new medium is to kind of try and push it to its limits, see what it does, how far you can go. So the first question in ethics is, ‘How far do we actually want to go?’ ” asks Sandra Rodriguez, creative director of Montreal-based EyeSteelFilm and instructor of Hacking VR, MIT’s first virtual reality course.

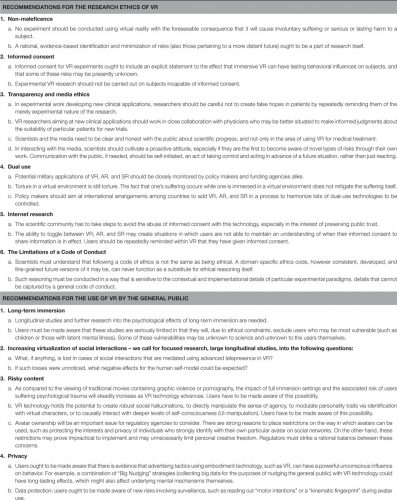

Ethics in VR, especially those pertaining to nonfiction storytelling, are fuzzy—Michael Madary and Thomas Metzinger, two German philosophers, published a code of VR ethical conduct last February to little fanfare or collective adherence. The field, it seems, will continue to move whether the science or ethics catch up or not.

But that poses serious questions for VR developers. Rodriguez’s most recent project admittedly has challenged even her own moral code. “We’re now really pushing hard for a project called Manic VR where you get to experience not what the world looks like when you’re manic depressive, but more tapping into the poetry of these hallucinated worlds,” she says. Adapted from a feature film, director Kalina Bertin utilizes answering machine messages from her older siblings, who both struggle with manic depressive disorder, to paint a picture of the condition while avoiding totally inducing the feeling. “The feeling of super powers that they have; the higher they go, the deeper they fall…this kind of cycle is both frightening and mesmerizing. And still beautiful,” says Rodriguez. “It’s interesting to bring that kind of poetry to make you feel like you want to be in that magical space forever, and then being sucked out of it very violently.”

But that poses serious questions for VR developers. Rodriguez’s most recent project admittedly has challenged even her own moral code. “We’re now really pushing hard for a project called Manic VR where you get to experience not what the world looks like when you’re manic depressive, but more tapping into the poetry of these hallucinated worlds,” she says. Adapted from a feature film, director Kalina Bertin utilizes answering machine messages from her older siblings, who both struggle with manic depressive disorder, to paint a picture of the condition while avoiding totally inducing the feeling. “The feeling of super powers that they have; the higher they go, the deeper they fall…this kind of cycle is both frightening and mesmerizing. And still beautiful,” says Rodriguez. “It’s interesting to bring that kind of poetry to make you feel like you want to be in that magical space forever, and then being sucked out of it very violently.”

Many of the initial fears surrounding VR were similar: that people would never want to leave the magical, constructed world of virtual life. But when it comes to immersive nonfiction, especially with projects that tackle intense subject matter like Rodrigues’s or De La Peña’s, that worry takes a backseat. Instead, users — and creators — are left wondering what will stay with the viewer after the headset comes off. The hope is overwhelming understanding, broadened perspectives and empathetic actions.

The effects in reality, especially long term, are virtually impossible to know.

- A quick tour of the science of virtual reality - October 16, 2017

- The godmother of virtual reality spoils us with insight - October 12, 2017