The New York Times’ Kevin Roose illustrates how memes radicalize users in online spaces

Valerie Gilbert is a Harvard-educated New Yorker and self-proclaimed “meme queen.” A QAnon soldier, Gilbert spreads information far and wide, fighting the global cabal of “Satanic pedophiles” that former President Donald Trump has been recruited by top military generals to dismantle. Her medium of choice, of course, is virtual ephemera in the form of internet memes.

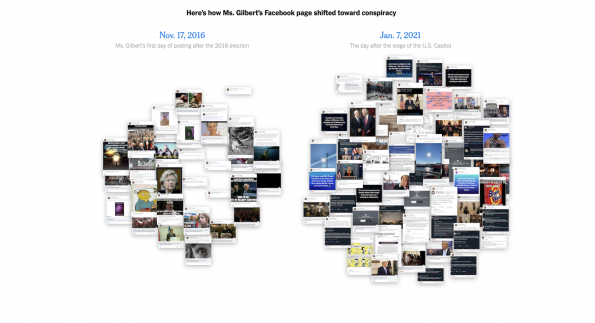

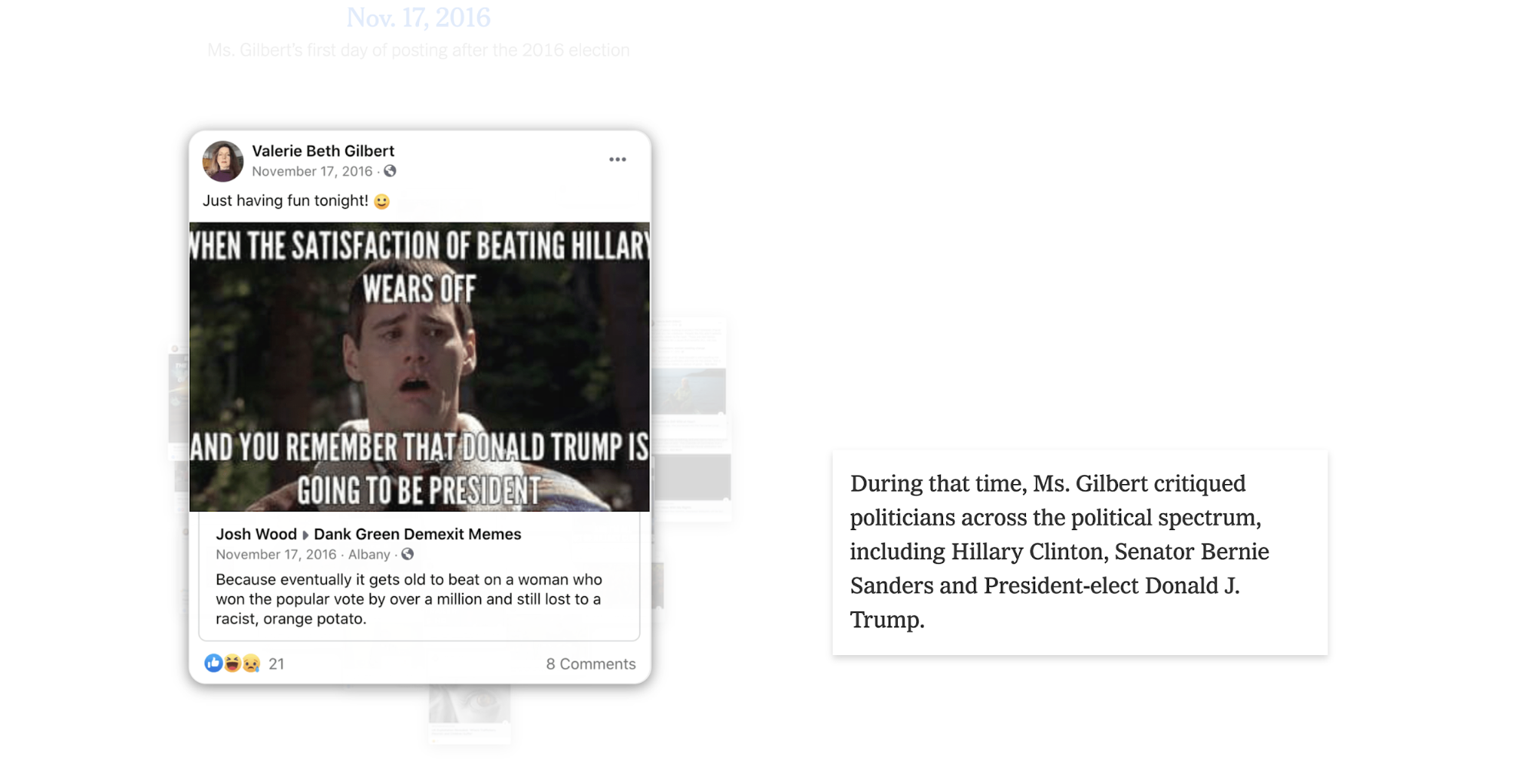

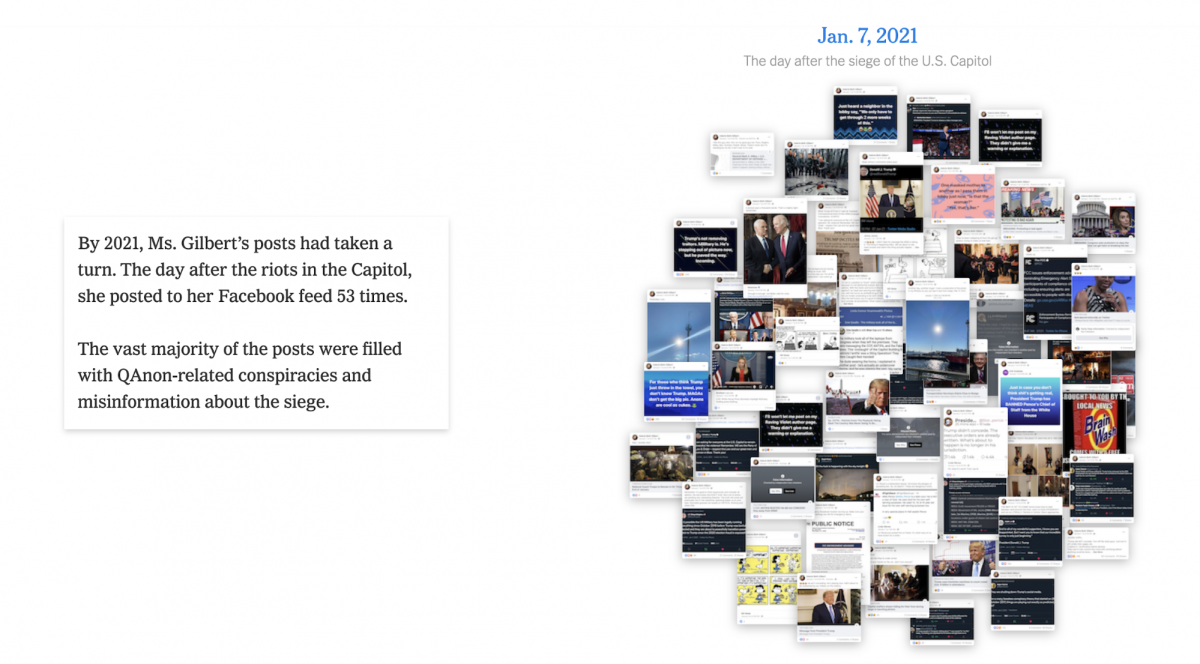

For his New York Times column “The Shift” which examines the intersection of technology, business, and culture, Kevin Roose explores how Gilbert was radicalized online by tracking the memes she shares. His piece “A QAnon ‘Digital Soldier’ Marches On, Undeterred by Theory’s Unraveling” couples traditional reporting and Gilbert’s voice with a visual spread of memes pulled from her Facebook page. The assortment conveys the path to conspiracy-oriented radicalization that the disillusioned, elite writer and actress took from pseudo-leftist to full-on QAnon.

Memes act as potent units of sociopolitical messaging, coding meaning and vast swaths of information in a minimum of space. There’s no denying that memes are one of the most important tools in an internet-era radical’s artillery of mediums, but Roose’s investigation aptly illustrates just how that path materializes. And the people who engage in this communication are hardly homogenous.

Storybench spoke with Roose about how this story came together.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get started with this story, and what was the inspiration? How did you find Valerie Gilbert?

I found Valerie maybe back in 2019. I was making a podcast, and I was really looking for people who would talk to me who believed in QAnon. I think actually one of my producers may have found her on Twitter, and she was tweeting about QAnon and was from New York, so it was appealing because we might actually be able to meet her in person. And so I got in touch, and she was willing to talk. She came in, and we did a long interview, and then it never made the podcast. And so I kept in touch with her and went back to her a few months ago and just said, “How are things going? What’s new?” And [I] just thought her story was one that needed to be told. I think there’s a stereotype of QAnon believers as being stupid or uneducated or sort of unsophisticated news consumers, and I wanted to show that that’s not necessarily true, that there are lots of very educated people — people with material advantages and good education that can still get caught up in these communities.

How did you get started writing about QAnon and that corner of the internet?

I cover the internet and social media, and … the Christchurch shooting was sort of the catalyst for me, for getting more deeply into extremism and radicalization online. That really affected me, and I think it was a sign that online extremism was not different from offline extremism, that it was no less serious and that often one led to the other. So that was really the time when I thought, OK, I have to dive in and explore this topic.

“It’s one thing to have her narrate the story of how she got into QAnon, but it’s really illuminating to actually see it. I think her Facebook page was telling the story in real time.”

Kevin Roose, New York Times Tech Columnist

The visual elements of your piece are really striking to me. There are so many ways that we can describe how memes affect offline culture or radicalization online and offline, but it’s really interesting to see this visually. We see how Gilbert’s posts migrated from discussing Jill Stein and veganism to this extreme right-wing space. How did these visual elements come together?

It’s one thing to have her narrate the story of how she got into QAnon, but it’s really illuminating to actually see it. Her Facebook page was sort of telling the story in real-time. You can see how she went from Democrat to Jill Stein voter who was disillusioned with the Democrats, to getting more into countercultural figures and sort of hacktivists — people like Julian Assange, and Edward Snowden, and she got really into the Standing Rock protests. So you can kind of see this worldview taking shape. I thought that was super interesting. I worked with some people on our graphics team to pull a selection of posts and just show kind of the progression. I think that sort of made it resonate for people in some way, because they could see, “Oh I know someone who posts these kind of memes,” or “I know someone who’s been on this kind of ideological journey.” So I think it really is a form that we’re all familiar with, and I think it added to the story.

I think more and more now, people are realizing just how powerful memes are. How are memes contributing to this radicalization, and how are they different from solely text-based mediums, for example?

Memes are sort of the most basic layer of political communication and strategy now, and we see politicians embracing them. We see companies embracing them. They’re a shortcut to getting people thinking and talking in certain ways. Memes are not just a political thing; they’re not just an extremist thing. They’re everywhere. And I think what the extremists realized maybe earlier than anyone is that you could use memes as part of an effective radicalization strategy. That if you just couched your most extreme beliefs in memes and humor, if you weren’t like an angry cross-burning white supremacist, but you were like a jokey online neo-Nazi, you could become more palatable to people who may have otherwise been turned off by your style. So it’s sort of a way to engage people in thinking about ideas without requiring them to have a serious — you can just laugh about feminism or the “great replacement” or something. If you can turn it into a joke, then you’re less likely to be turning off people who don’t agree with that ideology. And that’s part of the extremist strategy that’s been explicitly laid out: that people should never be able to tell when you’re serious or not.

“Memes are sort of the most basic layer of political communication and strategy now, and we see politicians embracing them, we see companies embracing them. They’re a shortcut to getting people thinking and talking in certain ways. Memes are not just a political thing, they’re not just an extremist thing. They’re everywhere.”

Kevin Roose, New York Times Tech Columnist

What do you think the future is for QAnon and for alt-right extremism that has traveled through memes? What do you think the future is for these communities in those spaces, in this changing sociopolitical climate?

Well, I think QAnon itself may be dying, just the idea of these insiders leaking information about government investigations and things like that — it’s not credible anymore, because Trump is no longer the president. I think that sapped a lot of the energy from the movement. But that’s not to say that the people who believe in QAnon are going to go back to reading the newspaper, or watching cable news and start becoming mainstream conservatives or mainstream liberals. I think they’re going to continue looking for conspiracy theories and for elite wrongdoing. It may not be attached to Q, but it could be this other sort of movement that grows out of QAnon. Memes and internet culture are really central to that, because part of the ethos of these communities is that you’re supposed to do your own research, that you’re not supposed to blindly accept things that are filtered through the mainstream media. And so a lot of that is aesthetic.

You know, people in QAnon trust the grainy memes that their friends are posting more than the things that are being said on the evening news. And it’s almost like an aesthetics of lo-fi information distribution where the worse something looks, the less polished it is, the more likely it is to be true, because it’s coming from this alternate universe of researchers and diggers and people who sort of assemble shards of internet rumors and old screenshots and Wikipedia pages. It’s like this forbidden knowledge that they’re accessing, and to them that feels more real than the sort of people in suits on the news reading off a teleprompter.

Do you think that there are many people like Gilbert, who are highly educated individuals with socioeconomic means, who are spreading this information and are members of these communities?

It’s hard to know exactly how many, but I’ve met QAnon believers who have more education than I do, who have more degrees than I do. There was an interesting story in the Atlantic a few weeks ago about the sort of data analysis of the people who were arrested at the capital riots and found that it wasn’t the sort of stereotype of angry young men who are left out by economic hardship and turn to extremism in a search for self-improvement or whatever. It was like CEOs and business owners and people with money and people with education. So I think it’s a mistake to just believe that this only happens to people in red states without much of a formal education. I think we now know that that’s not true.

What has the response been to this piece?

It’s been really interesting. I’ve heard from a lot of people who say, “This happened to my mom,” or “This happened to my brother,” or “This happened to my neighbor.” I think by now, QAnon and the conspiracy theory community that has grown up around it, it’s big enough that most people know someone who has gone down that path. So there’s a lot of frustration and sadness about that. But there are also a lot of people looking for answers. They want to know, like, how do I get someone out of this once they start believing it? How do I talk to them? How do I convince them not to go full QAnon? So I think there are a lot of people who are looking for solutions.