Adding depth to stories of immigrants with interactive visual storytelling

“Are you cold?” a tinny voice asks in Spanish from behind the camera.

“Yes, it’s really cold,” the small boy clutching his father’s hand answers.

In this home video, with which Theo Rigby opens his film “Sin País,” the father-son pair – clad in matching black jackets – is surrounded by wide open space, an immensity felt both physically and mentally by the Mejía family upon arriving in San Francisco from Guatemala in 1992.

“But, you are happy?” the voice, Elida Mejía, asks her son Gilbert.

“Yes.”

Years later, these members of the Mejía family would face deportation after 20 years in the United States. Gilbert, along with his sister Helen, would remain in the U.S. fighting for his citizenship, while Sam and Elida would be forced to return to Guatemala with their youngest child, Dulce.

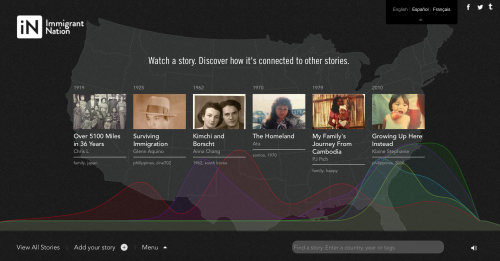

The Mejía family experience is only one of those told by Rigby in his expansive digital storytelling project on immigration, “Immigrant Nation,” or iNation. Most recently, Rigby has expanded his immigration reporting with research on the sanctuary movement.

Storybench sat down with Rigby to discuss his projects. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You have such a stellar portfolio of work that focuses on immigration. What professional experiences sparked your beat reporting?

About 12 years ago, I was really dissatisfied with the depth and the nuance of immigration stories in the media. There were a few independent journalists, filmmakers and storytellers working in that space, but in general, immigration stories back then really focused on the border – a U.S. and Mexico kind of story.

I decided to go down to the border and see it for myself, just to see what was actually going on and what the true story was. I eventually met a mom who had 14 kids and had crossed over the desert with seven of them. She was still living in Arizona, undocumented and with many children who were undocumented, in a town where there was a border patrol station.

That was how I got into immigration stories. A year after the project got started, that family got picked up by the border patrol and went through the immigration justice system. My role changed as I helped them raise money to get out of jail and found a pro bono lawyer to take on their case. I continued telling their story and saw the intricacies of life for this one undocumented family in that specific place in Arizona.

I get asked a lot when I do presentations or screenings, “Why immigration?”

Well, that was the inception. All of these issues are pretty abstract to people who don’t have contact with the undocumented community in a profound way.

I came back to San Francisco and started a storytelling program for undocumented youth. There, they could tell their own stories in their own voices, rather than me creating stories in the “immigrant voice.”

From your work with the family that crossed the border to the family featured in Sin País, do you find that people in these vulnerable situations are comfortable talking to you?

I get asked that question a lot: “How do you get undocumented folks to agree to be a part of stories that are going to be public?”

I’ve often worked with people who are already in the system, like the family featured in Sin País. They were fighting their deportation and wanted me to advocate for their case.

My latest film, Marathon, is about this man who came to the United States 17 years ago. He saw the New York City marathon on TV and said, “Hey, I want to do that!” And through incredible hard work and dedication, he is now one of the fastest runners in his age group, albeit undocumented and working as a prep chef in a kitchen many, many hours a week. He is not in the system, but he is in a part of the country where he doesn’t feel all that at risk sharing his story.

I think clearly stating your intentions from the get-go, as well as the possibilities of where your story could go and what could happen as a result, is important. What are the possible negative ramifications? If you’re genuine, people see that honesty and have all the information they need to base their decision on. At this point, I have a body of work that I can point to and say, “Hey, I made this piece and this is where it is in the world and the visibility that the piece I’m proposing to you could have. Are you still in?”

Very often people say, “No, I don’t want to take that risk. I’m not ready to have my story out there right now.” And, like with any story, you may have to approach a wide array of people before finding the perfect person to tell that story.

iNation incorporates a lot of different modes of storytelling, but they are all visual, as your portfolio of work on immigration has been. What are some of the benefits of visual storytelling? What makes visual storytelling so captivating?

So often, after doing screenings of my films, I have people come up to me and say, “I never knew. I never knew that this is the reality for this community that I’m living side by side with.” People might live a mile away and yet live in a vastly different world than the immigrant community. Often, immigrants are geographically segmented away from everyone else.

I think the power of documentary films is to be able to have a short moment to really see, hear and live in that unique experience that is, in my case, the experience of the undocumented – a community that doesn’t have a loud voice.

How do you envision iNation in its entirety? Do you consider that to be your ongoing portfolio of work, or is it a specific, defined project?

I am currently trying to figure that out, the container for the work that I’m doing.

The iNation project as we’re talking about it is a series of short films, an interactive web platform, a resource guide and a series of live events around the country. Though that project has wrapped, teachers and educators continue to use the storytelling platform in classrooms to engage youth in their personal narratives and engage in curriculum around identity and the immigrant experience.

Since I am dedicated to telling stories of the immigrant experience, I’m moving toward starting a new company, potentially a non-profit, that will likely be called iNation. I see it as a media company that creates narratives around the immigrant experience. The interactive is part of this larger body of work. I hope to hire staff and have a team of people working on these issues so that, when surprises like the election happen and immigration policy changes and stories rapidly develop, I’m able to pivot and create different projects in different ways but all under the container of a core team.

I’ve been working on a project on the sanctuary movement, which is when faith communities take in refugees or undocumented immigrants and shield them from deportation and rally around them to try and get some sort of legal status. The sanctuary movement is going to take off exponentially in an era of increased enforcement. I’m working on telling that story and looking ahead to see how the elimination of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) affects the independence of young undocumented people.

How has collaboration contributed to iNation thus far?

I tend to engage strategic partners from the start. I ask myself, “Who is strategically aligned with the narratives that I’m trying to get out in the world? Who can help with casting- finding the people who are going to tell my stories- or distribution?”

With iNation, I had a really amazing producer, someone on social media, an impact producer, a design development web team to build the online platform, as well as researchers and assistants to come in as needed. And that’s not even part of making the actual films.

Being able to collaborate with an immediate team to tell the story as the project grows and as funding comes in emboldens the work in so many ways.

Is there a recent digital piece that incorporates powerful visuals, interactive elements or data visualization that has stuck with you as a model of this type of work?

I think there’s a lot out there. I tend to take small pieces of inspiration from a lot of different things. For the interactive, we would look at 10 different interactive projects, radio projects or video projects and say, “Wow, I really like the data viz that they built for that,” or “Wow, I really like the user experience on this piece,” or “Wow, I just get totally enveloped in the story on this piece.” We wanted to replicate the engagement that you get with narratives of that design.

There are some great databases and containers for interactive work. One is Docubase, out of MIT.

If you were to design your own graduate course in whatever you’d like, what do you think it would be?

There are a lot of classes that I didn’t have in my formal education that I would have loved to have had. For the most brass tacks useful class, it would be business – the business of being a storyteller, filmmaker or photographer, mostly on the freelance side of things.

I never really got a lot of guidance in terms of how to build a business, how to talk to clients and how to come to agreements with the people you’re working for and those who are working for you. That’s often the advice that people come to me for when they’re first out of school; we often tend to underbid and undersell ourselves, especially at the beginning of our careers. I’d had a leg up because I’d already been a freelance documentary photographer for a long time, but it’s something I definitely struggled with. Now, more than ever, we need independent voices that tell the story of our time, and a class on how to create a sustainable life as a freelance storyteller would help to ward off some of the attrition that we see. That’s it: The Business of Sustaining.

You shifted gears from photography to videography. Do you have any advice for anyone who wants to do the same?

I’ve been out of the photojournalism game for a long time and a lot of things have changed. As you know, news organizations and media organizations often ask people to be a lot more than just a still photographer, and to record video, to record audio, to make packages of things. There’s a lot of crossover, especially between being a still photographer and being a cinematographer or a DP, a director of photography.

In the world of filmmaking, it does help to have a specific skill set that you get to be known for and then get hired for. So, if you are a photographer looking to crossover into the world of filmmaking, I would suggest trying to get jobs and work as a DP or cinematographer in one subset of filmmaking. You can try and do everything, be a one-man band of shooting, editing and producing, but, if you’re looking long-term, figuring out what you’re passionate about and what you want to dedicate your time to is the best.

Theo Rigby, Thank you for your ongoing creative work. I met you in Seattle at an international conference on Immigrants & Refugees. You gave me a copy of Sin Pais and I continue to share the documentary with my college students. I’m grateful you continue to stay with the work to provide the dignity of stories to uncover the lives of immigrants at the U.S. border.