How a husband and wife team exposed the dangers of tanning factories overseas

Have you ever thought about the true cost of fashion? Last year, in a series published by Undark magazine with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, photographer Larry C. Price explored the leather industry’s effects on tannery workers – including children – in Bangladesh. Debbie M. Price, his wife, wrote the stories to accompany the photographs with on-the-ground support from journalists in Bangladesh and Indonesia.

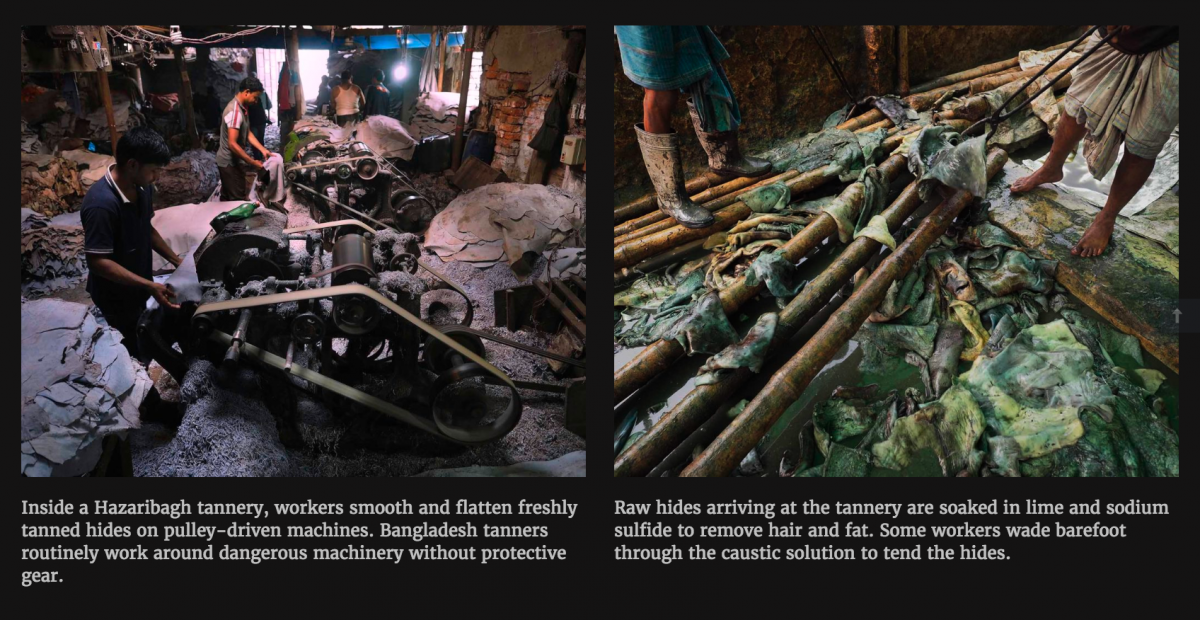

The article, “Skin Deep: Feeding the global lust for leather,” highlights the dangers inherent in unregulated tanneries in parts of India and Bangladesh, where Larry photographed children and adults working in dangerous environments without protection.

Storybench spoke with Price on the project.

What kind of particular situations did you try to focus on in your article?

The stories that we did focused on two particular situations, one being: the leather production industry in Hazaribagh and, in this case, there is a tannery district — that has since been shut down — and they have completed moving all those tanneries to an area outside of a town called Savar. And while we haven’t been back to Savar, we understand that Savar does have a central waste treatment facility. Now, the concern is that they’re going to take some of the bad practices and they’ll keep doing them in Savar.

There were a lot of factories that were dumping their waste into the river and that’s a problem. But not all textile companies do that, not all fashion companies buy dirty materials. You know when we did the stories in Hazaribagh, we talked to leather companies and shoe manufacturers and people that sell in the United States, and as you saw at the bottom of the story, several of those — Timberland in particular — said they didn’t source from those who make products from Bangladesh, they didn’t source their leather from Hazaribagh, and that they try to source from tanneries that meet standards of the leather workers guild. So, I think it is a problem in certain areas, and I think the way that we can address this as consumers is to ask the companies that we buy our clothes, our shoes, our purses from, to provide more information online about where they source all the raw materials, and where they have their products made.

The photos are very impressive. What did you think when you first saw these pictures?

Larry took all of these photos by himself. I knew what he was doing, I knew what he was up to, so I was not surprised because I knew what the circumstances were likely to be. It’s horrifying, though. It is horrifying to see anyone – a man, a grown man – dunk their hand into the water that’s full of chromium and chemicals. It is very disturbing and concerning, but what’s really upsetting is you see little children working. It is so dangerous.

It’s a concern, and it comes back to the American fashion companies where we buy our clothing from. You know, we need to ask them to be as clear responsible and they shouldn’t buy their material from the industries that labor children. You just don’t use children and you protect your workers. And that became a standard that forced everybody to play by those rules and, those people who don’t, lose their business. So they have to do it. So that’s the ultimate goal – use ethically sourced materials. And be willing to pay for it.

In your article, you write, “It has been seven years since the Bangladesh High Court ordered the government to move or close Hazaribagh tanneries.” Why is it taking the government so long to act?

When my husband went back to Bangladesh to do another story, he said those tanneries finally got some pressure. But you know, the country is a developing nation, it’s becoming more advanced. It took the government a lot longer to deal with new facilities. The government didn’t want to just shut down the tanneries because the tanneries are the major source of income for those people who live there, it’s a major part of their GDP, their major export. So, sometimes it just takes a long time to make things happen, especially if you are in a developing nation that doesn’t have instructions, so you have to build it. And you don’t have the scientists, the engineers and all the people that can make things happen quickly.

How long did it take you to report this story?

(My husband) Larry Price traveled to Bangladesh and Indonesia to photograph the stories. He spent about three weeks in each country. I came into assignment late in the process to report the story from the United States and spent about two months working on the four stories. We hired reporters living in those countries to help us with additional on-the-ground interviews and with translations. I also worked closely with Larry, deriving a lot of information and description from his observations, notes and photographs. Additionally, I used the Internet to research published studies, some of which led me to Mohammad Abul Hossain and his study about chromium in chicken feed. I interviewed him via Skype and we continued to converse via email. The stories in the United States I reported via phone interviews with people in New York and North Carolina. Larry also traveled to New York (twice) and to North Carolina to photograph the stories. And again, his observations and notes were very important to the writing of those stories as well.

What kind of difficulties did you encounter when you were reporting this story?

Both the Bangladesh and Indonesian stories were developing and changing as we were writing. In Bangladesh, there were government orders pending to close the tannery district. In Indonesia, there was a court case pending that could have shut down several textile and clothing factories along the Citarum. We had to monitor the developments in both situations from the United States. With the language barriers and inability to access court files online, that was difficult – and required the assistance of reporters living in those countries. Locating a reporter in Indonesia who could work with us also was a challenging, but ultimately I was able to connect with Joe Cochran, who is a true pro and did a great job. Paulash, our friend and noted Bangladesh photographer, worked with Larry in Dhaka and was very helpful to me afterwards, conducting additional interviews with tannery owners and providing updates on the government order to close the tannery district in Dhaka. Government authorities in both countries were fairly non-responsive.

Why is this story important?

In Bangladesh and parts of India, the leather tanning process is highly polluting and dangerous for the workers. Along the Citarum, textile factories are freely dumping toxic chemicals into the river that supplies drinking water for millions. Products made in polluting tanneries and factories reach the American market. I think it’s important that consumers know where and how the products they purchase are made, so that they can choose to purchase responsibly – and demand accountability from American companies. Also, international pressure – including the stories published in Undark – is effective in persuading governments to take needed action to protect their citizens. Shortly after the Undark article ran, the government did finally enforce the order to close the tanneries Hazaribagh. Larry returned to Bangladesh late last year for another story and found all the tanneries closed. We also need reminding here in the United States how valuable our clean air and clean water is – and how important regulations are to protect our environment.

How did you pick your sources?

We identified potential sources for all aspects of the stories and then tried to find people who would talk with us – people in key governmental positions, tannery owners (in Bangladesh, India and the US), textile factory owners in Indonesia (a lawyer representative) and in North Carolina, public officials in the US in Gloversville & North Carolina, residents, workers – essentially all the stakeholders. We also did extensive research via published studies and other news accounts.