Using data from books to measure cultural evolution: A primer on Google’s Ngram viewer

Books are one of the oldest and best “tools” at the disposal of the common man who wishes to live a thousand lives, and to fully comprehend foreign times, places, and lifestyles. Through the words in a book, we can go back and forth in time to experience a life different from our own. However, one’s view of a book may be drastically different than that of the next person and it is always hard to draw absolute conclusions about our evolving culture from books.

That is why the promise of Google’s Ngram viewer – to bring in quantitative analysis to the study of cultural evolution – is so captivating. The company extracted data from 8 million books – spanning from 1800 to 2000, with more than half a trillion words in English – to make sense of cultural changes and human identity over time.

What have people concluded from Ngram searches and what are the pitfalls in trusting that dataset?

Erez Lieberman Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel published an article on Science in 2011that investigated the possibility of measuring cultural evolution. A new term arose from the findings: “cultoromics.” Here’s a look at some of the findings:

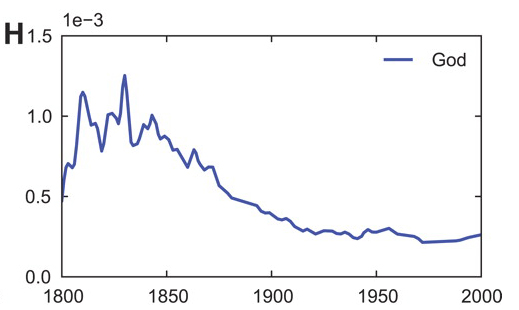

God is not dead, but needs a new publicist

Looking for the word “God” in all the books published from 1800 to 2000, we can see the popularity of the word over time in the English language.

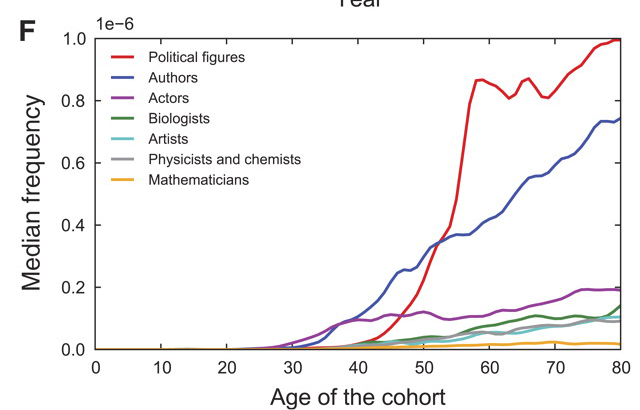

There’s still time to become famous, but head to D.C., not Hollywood

After identifying the 25 most famous people born from 1800 to 1920 in seven different professions and investigating how old they were when they rose to fame, the researchers could conclude that, even though politicians usually turned famous at age 50, they became the most famous, and much more quickly than actors, writers, and scientists.

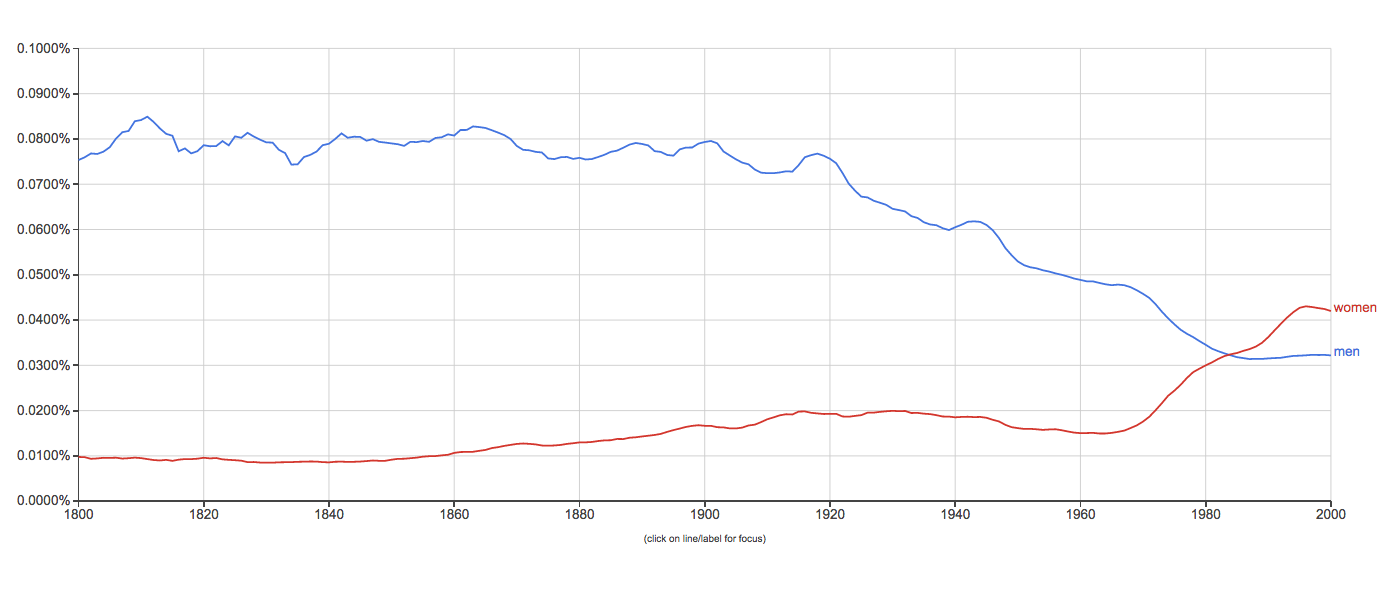

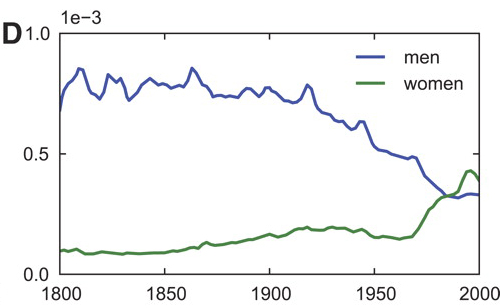

Women took the lead in the battle of sexes in the 1980s

For at least 170 years, the word “men” has appeared more often in books than “women.” This changed sometime around 1970, when “women” started to gain ground and eventually surpassed the use of the word “men.”

If it sounds too good to be true, look again

However, another study, this time published in 2015 on PLOS by Eitan Adam Pechenick, revisited the promise of measuring cultural evolution by only considering the frequency of a word appearing in books, and shed light on the shortcomings and challenges of using the tool for that purpose.

For one, the researchers point out that Google Books registers one copy of each book, so a popular book with multiple editions has the same weight in the data set as an unpopular book, which might create a misleading notion of frequency.

The paper also questions the data sample that Google Books runs to get the graphs. According to the researchers, the data set gets increasingly inundated by scientific publications starting in the 1900s. “When examining these data sets in the future, it will therefore be necessary to first identify and distinguish the popular and scientific components in order to form a picture of the corpus that is informative about cultural and linguistic evolution,” the researches warn.

The study also notes how long it takes for events in life to get told in books. “Analysis of the emotional content of books suggests a lag of roughly a decade between exogenous events and their effects in literature, complicating the use of the Google Books data sets directly as snapshots of cultural identity,” according to the study.

Because anyone can retrieve the data behind Ngram charts using Python code, the study is an important framework for future projects that use the tool to measure cultural and linguistic evolution.