How investigative journalists followed the money in the Pandora Papers

The day when Miranda Patrucic got a call from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists about the Pandora Papers leak, her jaw dropped.

The Pandora Papers are leaked documents that revealed hidden wealth, tax avoidance, and in some cases, money laundering by some of the world’s most powerful government officials, business leaders and celebrities with tax havens in places like Switzerland, Dubai, Panama, Monaco and the CaymanIslands, to name a few.

“I have to say that if all of us that are here currently present at this conference got together and worked for the next 10 years, we still would not be able to publish all the stories that are hidden in the data,” said Patrucic, deputy editor-in-chief at Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project on Friday at the NICAR conference in Atlanta.

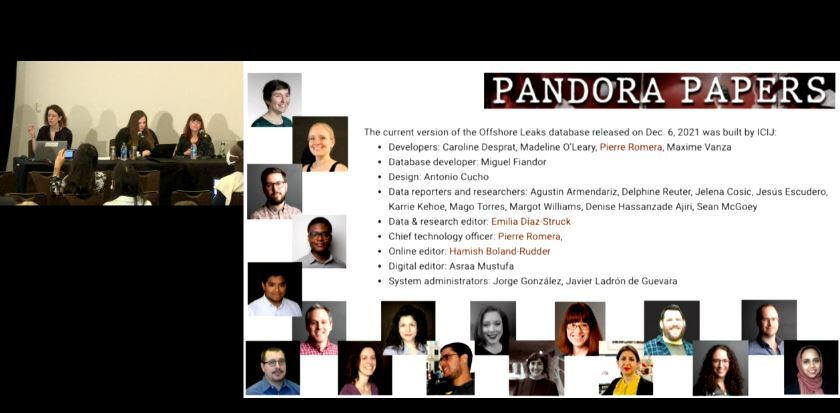

The trove of 11.9 million files, close to 2.94 terabytes, with 14 different offshore service providers as sources, was the largest leak of offshore data in history. More than 600 journalists have combed through the documents as part of a large global investigation. The ICIJ’s first reports were published in October.

The files, spanning five decades, provide an unprecedented window into how the world’s wealthy hide their money and assets from authorities, creditors and the public, by using a network of lawyers and financial institutions that promise secrecy.

According to Delphine Reuter, a data journalist at ICIJ, a lot of firms that they were investigating at that time were from the British Virgin Islands. In June 2017, the Beneficial Ownership Secure Search System Act, or BOSS Act, came into effect, through which any firm that had BVI companies that they were providing to their clients had to tell British Virgin Islands authorities who the beneficial owners were.

“We had a lot of information in the documents because of this act,” said Reuter.

The data

The team worked with data from 14 different offshore service provider sources, which is a lot higher than the usual one or two such sources for other stories. The diversity in how the information was presented and collected resulted in a huge data challenge.

Early on in the project, the team identified specific documents to use and structure it to share with collaborators. They also spent months extracting information into spreadsheets.

The Pandora Papers contained forms with actual signatures of people, email and internal correspondence. “These are things you couldn’t get in any way from offshore providers,” said Patrucic.

She reported on the Aliyev family in Azerbaijan, which had over 100 companies in the leak, some of which held assets worth $700 million in London.

“For many of them, we never figured out what was the real purpose and how much money actually went through it,” said Patrucic.

She built her own spreadsheet to see patterns in time such as 15 companies changing directors at the same time, five companies that were set up or dissolved at once, changes in directors that were made and more. While for many of them the team was able to find properties in London, said Patrucic, they still needed more public records to find out locations of properties, their purposes and finances.

Census data confirmed the addresses of people given in databases, land records and different government records, especially in the United Kingdom.

“It was amazing because we could see the name of the offshore company that was in Pandora Papers basically was the one filing all these records in the U.K.,” Patrucic said.

Findings

The files exposed how some of the most powerful people in the world, including more than 330 politicians from over 90 countries, used secret offshore companies to hide their wealth.

Reuter said that while trusts are commonly used by people to structure their wealth and organize for people after them to have access, they are also used by people in different countries to hide their assets.

A big effort that the team made was to look at all the politicians and public officials that it could identify in the data. In the end, they had over 1,600 rows for more than 330 politicians. Given the scale of the project and that it was a long term investigation, the team had to develop a tool that was adaptable.

It’s important to source the research very well so that journalists know where in the data specific bits of information are located, Reuter said. It is not enough to link to documents, she added, data journalists should put in the additional effort to explain why specific decisions were made. Detailed documentation comes in especially handy if the team is spread across countries and time zones.

Power Players

This effort materialized into the visualization Power Players, which is a term the team uses for investigations that look into people of power, some more important than others, who use offshore to stash money away from the public eye.

Power players provided detailed profiles of who these people are are, how they use the offshore world, the kind of companies they had, and more. Some of the data was then integrated into the Offshore Leaks Database.

Things to keep in mind

- Research and fact checking usually do not happen at the same time, so it’s important to give enough time for research, accurate sourcing and outlining detailed methodology.

- For teams distributed across the world, be sure to organize so there are no bottlenecks.

- Researching → Fact-checking → Resolving → Closing.

- Allocate space and time to address disagreements.

- Color is your friend. Sometimes you have to agree on the type of green to use (basic but important).

- The number you see in the story is the number you ended up with. A lot of the data work is not visible.

Databases and Tools Used

Orbis to get the list of all subsidiaries of offshore companies

Patrucic mentioned that Orbis is not good with offshore records, but once you have the name of a company, it is a great place to find out what subsidiary it has and its location.

LexisNexis to get previous news articles and find out whether BVI companies were dissolved because information in Pandora Papers was cut off at some point.

Aleph by OCCRP

Has all of the U.K. properties owned by overseas companies. Was useful to check each company in Pandora Papers whether it owned a property in the U.K. Patrucic said that because the companies have a life that goes beyond the leak, putting several leaks together allows one to see their footprints over time.

“You really need that as a reporter because it gives you more and more places for your story, more reporting avenues for your story,” she said.

Patrucic noted that for any investigation she does, if anything leads offshore, she uses the Offshore Leaks Database as her first stop.

Prophecies by ICIJ

Available on GitHub for people to download

Datashare by ICIJ

- Platform to access documents, batch searches, tagging, filter by file type, date and more.

- Powerful when you have multiple documents to sift through and need to zoom in on specific types of leaks.

- Also has a tree structure: If you find a document by keyword search, you can actually see in which folder it is located in.

Allows specific projects within groups and topics of hierarchy, making it easier to exchange information, organize collaboration and post findings

Other tips

- How investigative journalists followed the money in the Pandora Papers - March 4, 2022

- Federica Fragapane on Using Minimalistic Shapes, Lines and Tree Branches to Convey Powerful Stories - February 28, 2022

- Of Data, Theater and Healing: The Art of Federica Fragapane - February 21, 2022