Investigating megabits: How Leon Yin and The Markup uncovered the story of ISP inequality and digital redlining

In the pandemic transition phase of 2022 and onwards, it has been common for many people’s workdays to take place at home, fully remote. But in most large cities across the United States, the quality of equally-priced internet service experienced in two households just blocks apart can be worlds away.

In a recent data-driven investigation, Leon Yin, a computational journalist at The Markup, found that these neighborhood internet service gaps occur on pre-existing lines of racial disparity and income inequality — known as “digital redlining,” in reference to the historical practice of dividing up cities into “good” and “bad” in terms of home financing.

“The best and still desirable areas tended to be affluent or middle-class white collar, and the areas that were deemed hazards tended to have people of color and immigrants,” Yin said at a December 2022 lecture to computer science and journalism students at Northeastern University’s Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering (ISEC) Complex.

“The harms associated with redlining,” he noted, “have an extremely long pathway, meaning that even today, areas that were deemed hazardous still have higher rates of harm that range from asthma rates to gunshot injuries to infant mortality rates. And indeed, when we looked at internet access and speeds, it was no exception.”

Building off of research conducted in nine states by Princeton University and expanding it to 44 states, Yin and his colleagues, including co-author Aaron Sankin, were able to put paint an alarming portrait of internet service providers (ISPs) in the United States.

For example, with AT&T, they found that for the same price of $55, residents of the poorest, least-white areas in some cities can expect internet speeds up to 400 times slower than their most-white, wealthy neighbors. Households with what Yin described as the “worst deals” had speeds below 25 megabits per second — which falls below the FCC’s already-low threshold for broadband internet. This practice of equal pricing for unequal service is known as tier flattening, and it is employed by several of the largest ISPs in the United States to conceal the extent of their service discrepancies, critics say.

Visualizing the digital divide: how often homes in historically redlined areas were offered internet speeds so slow, the FCC doesn’t consider it to be broadband. pic.twitter.com/Ql2SokA3En

— Leon Yin (@LeonYin) October 19, 2022

Arriving at shareable, headline-worthy, easily digestible figures took Yin and team months of data-scraping, compiling, categorizing, double-checking, and bulletproofing. (See the team’s data and code at GitHub.)

Categories were created for internet speeds, from slow (below 25mbps) to blazing (200mbps+), for income, in quartiles from “lower” to “upper” based on an area’s median incomes, and for race and ethnicity, also in quartiles, from “least” to “most white.”

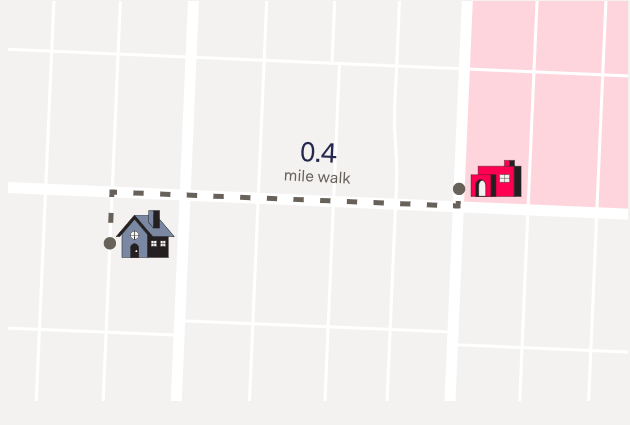

Further, they searched through hundreds of thousands of addresses from dozens of cities by using that city’s primary ISP’s address lookup tools to assess internet speeds and to find where the “worst deals” were. The team later merged that mapping data with historic redlining maps from 22 cities.

“The best and still desirable areas tended to be affluent or middle-class white collar, and the areas that were deemed hazards tended to have people of color and immigrants… When we looked at internet access and speeds, it was no exception.”

Leon Yin

In Yin’s story, the narrative at the end of the long road of data analysis emerged clearly: he found that the slow-speed, digitally redlined areas of 2022 often matched the historically redlined ones on a map — a powerful visual example of continuing inequality spanning generations.

“Ultimately, all this data really just boils down to sentences, right? That’s something that I always encourage in people doing data work. What’s the actual sentence you’re trying to write?” said Yin, as he explained how to make sense of months of hard data work. “Because data is distracting, and it’s especially distracting when you’re the one doing it because you get lost in the technical minutiae of the little choices. But it’s important to remember what the narrative is, and what that data means.”