Ten principles for photojournalists

It’s bound to happen. Sometime in your career as a budding photojournalist you will encounter the challenge and privilege of building a relationship with another human being in order to frame them accurately for a story. Many times this subject will have a vastly different worldview than your own and you’ll know that they need to be at the crux of your story. You’ll know it when we look into their eyes, the evident fragility of their situation. You’ll want to capture it.

But it is how we treat these subjects in pursuit of the authentic shot that is everything. While it is hardly possible to suggest a concrete list of technical skills to employ (given the wide scope of possible subject matter), there are a few widely accepted dogmas that can allow us to engage with any subject in a more meaningful way.

Boston Globe photographers Matthew Lee and Stan Grossfeld have more than 50 years of combined experience as photographers for a wide variety of news organizations. Each has encountered groups representing different demographics of day-to-day society, whether gangs, victims of natural disaster or indigenous peoples. Their respective work has gained each of them the coveted Pulitzer Prize. Storybench sat down with them to understand the principles that serious photojournalists should follow in order to become effective and compassionate storytellers.

1. Always initiate contact

“Pressing the shutter release can feel like nothing short of exploitation in these moments.”

As a photojournalist, you’re taught to be brave while sniffing out a story. Knocking on doors and calling potential leads should be second nature to you. But when you’re confronted with someone whose life is obviously wrought with struggle, it can be intimidating to ask the tough questions or to take the emotional shots. Perhaps it is a rape victim that battles with recounting the gritty details of the moment they were assaulted, or a returning veteran with PTSD. Pressing the shutter release can feel like nothing short of exploitation in these moments. Sometimes, however, pushing yourself to initiate dialogue can just be the thing that keeps you safe as a photographer; it should never be a habit we take lightly. Take Lee’s account of covering gang violence when he worked for the Oakland Tribune in California.

“I did a story on the toughest police beat in the area, back when the region had over 250 homicides a year,” recalls Lee. “And the one thing I always do whenever I’m in a tough neighborhood, I always initiate contact. If a brother comes walking by, they often ask what you’re doing. There is so much hidden agenda in their world, so if you’re just upfront and honest and say, ‘hey I’m doing this story for so and so,’ you’re better off. If you’re clumsy and awkward, gang members will sense it, take offense to it, and take advantage of it.”

No doubt the barrel of the camera can feel like a loaded weapon when a subject is caught unaware. Clarifying intentionality may be the surest way to show respect and give your subject agency. Once a conversation is started, you can always take a second to open the subject up before getting to work. Which brings us to our second point.

2. Have a conversation before shooting

Okay, maybe this seems like something you might hear from a commercial photographer trying to distract kids in a studio, but Lee insists that this has been the preferred trick to demystifying his process for so many of his subjects.

“Sometimes I’ll point out something in the room, or space – maybe memorabilia or a hunting trophy,” says Lee. “I did this with the President of Bank of America a few years back and I learned that when you point out something people love, something they’re passionate about, their excitement tends to distract them (or at least put them at ease) from the camera. It’s amazing and works almost every time!”

Talking to your subject about their wants and fears not only humanizes you to them, but provides context for how you might frame them to exemplify the tone of their experiences. It allows them to feel comfortable emoting which, according to Lee, isn’t something you should shy away from either.

3. Emote

A stiff upper lip and detachment from a horrific scene or tragic circumstance may otherwise seem intuitive in the field of journalism. And yet, both Grossfeld and Lee argue that photojournalists need to make it a part of their job to emote. In essence, the shot you take is the shot your viewers and readers will see, so if it’s not affecting you in any way, why would you take it?

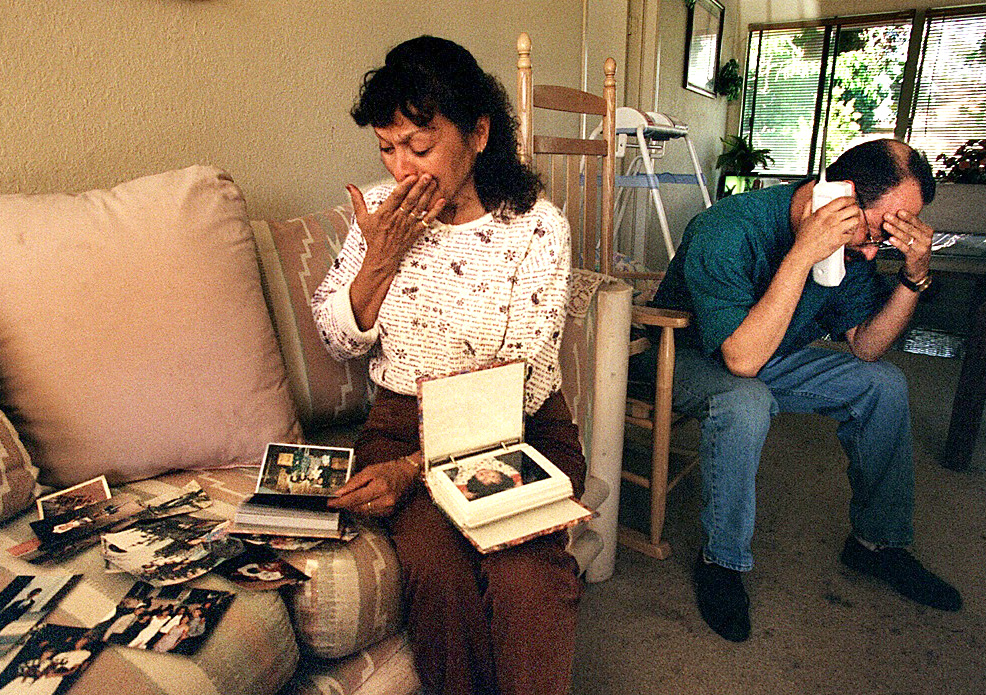

“I covered a horrible car accident when working for the Long Beach Telegram,” Lee explains. “The family’s vehicle caught fire on the road, killing them all. I went to meet with the surviving family members and suggested to the grandmother that she look through her shoebox of photographs and pick out five that she wanted to represent her loved ones in the story. So she’s looking through them, and I start taking photos, and at that moment, her hand is covering her mouth and she began to cry. That photo ran on the front page the next day, and someone anonymously paid for the entire funeral cost…So, the day you don’t feel horrible is the day you should retire.”

4. Try to offer subjects some license to their portraits

“ You never know when a story requires you to return and document the passage of time.”

Even in this story, Lee offered to show the grandmother the photos he’d taken before going to print. This one isn’t a hard and fast rule, of course. Humans are naturally self-critical when looking at a photograph of themselves. You’ll certainly need to weigh this as an option, particularly when doing investigative work. Nonetheless, when it is applicable to offer your subject a peek, knowing you’ll still walk away with a photo for print, do it. Ultimately this underscores the photojournalist’s job to be transparent and thus strengthen trust with this person, which comes in handy when needing to contact them with any follow-up questions.

Members of the community should play an active role in shaping how you represent them, since they can provide insights that are invisible to outsiders. Follow-up is also important. You never know when a story requires you to return and document the passage of time. Maybe a civil war doesn’t end for several years and you are asked by your editor to circle back to the battleground and see how a certain family is doing. You should always be cognizant of your presence as a person and not just as a photographer.

5. The golden rule isn’t dead

Grossfeld and Lee both point out the dangers of off-camera work. Over the course of his career, Grossfeld recounted numerous colleagues that were too aggressive with their subjects. In forcibly trying to extract an intimate moment from people, such photographers leave only burned bridges for the next journalist who comes around looking for a story. For Grossfeld, it’s as simple as following the ‘golden rule.’ Be kind to everyone: You never know if you’ll need to see them again, or if a future colleague might.

And maintaining a healthy off-the-job presence with the public is paramount. Lee had to learn this the hard way. “One time I was in just the worse mood after work, just full of piss and vinegar,” explains Lee. “A panhandler approached me with conviction and for whatever reason I wasn’t having it and snapped at him. I told him to just get away and stop bothering me, got in a screaming match with him! Well it wasn’t long after that when my editor told me to cover homelessness in a nearby park… The first person I saw was the guy I told to screw off… I wasn’t surprised when I couldn’t take any pictures that day.”

Whatever the case may be, your composure matters, on and off the job.

6. Do your homework

This is particularly true when writing a story that transcends cultural boundaries. For Lee, many beginner photojournalists seem not to recognize their economic or cultural status when starting out.

“This can cause some tension,” he cautions, “especially if you try to wing it in a depressed slum or ghetto.” And if you’re bound for international beats, like Grossfeld was, meticulous research of cultures will save the story. If you don’t, Grossfeld warns, you might seriously offend your subject and then you’re stuck on the other side of the world fighting to get even one shot to offer your editors.

“Every culture has something and it’s you’re job to be prepared for it.”

“Some of the young people today don’t want to do the research – no offense,” says Grossfeld. “At one point in Siberia a tribe offered me horse meat and I knew, from my research, that refusing it would have been insulting them. You had to become a squirrel and stow it away in my cheeks. But it’s not just indigenous people either. It’s the whole world. Every culture has something and it’s you’re job to be prepared for it.” That said, a smile and a good demeanor can make up for being naive to a culture’s idiosyncrasies, points out Grossfeld.

7. Always be on a swivel for medical professionals and police

Whether covering marches, crime scenes or war zones, you’ll always be searching for a good vantage point. But in the heat of an emergency, you may go from being a respected worker to an unfortunate obstacle. Capturing tragedy is always controversial, but it’s especially detrimental to one’s career if taking the shot meant delaying the work of medical professionals or the authorities. Lee attributes his healthy relationship with Boston police to years of not getting in the way of a crime scene.

“Because I knew when to back off or move around to get a better shot elsewhere [in the past], they always tell me what’s going on when I arrive on the scene,” he explains. “There’s been so much mutual respect in the past few years because of that.”

8. Remember your photos can and will go viral

Your photos have weight. This can’t be overstated. Once you’re able to shoot with emotion, you need to go one step further and think about how your composition tells the story and how the public will receive it. What does Lee’s picture of the grandmother say about her? That she’s vulnerable, that she’s weak? Does ensuring that the photos in her hand make it in frame change the photo? The answer is absolutely. Your photos have weight. Don’t just shoot to your own understanding. You wouldn’t do that when you write, so don’t do it with photography. Shoot while considering how the average audience member will interpret the photograph.

9. There’s always something more to learn

“I can’t tell you how many interns will come under my wing and I say one thing about aperture, or shutter speed, and I get, ‘I know, I know, I know,’” said Lee. “Listen as if you know nothing. Whether you’re photographing the vulnerable or not, you may learn a thing or two if you just wait. The fruit of my points to young photographers has always been at the end. Be patient like a dry sponge!”

10. Don’t seek controversy, seek the truth

The pressures of buyouts, mergers and the shuttering of countless news organizations has put photojournalists and writers under duress. Yet, if the last nine examples haven’t made it yet clear, your shots matter… to everyone. Controversy does not connote success. If your photo is not instructing society, revealing some truth, or spotlighting an injustice for the greater good, then you need to ask yourself why you’re doing it.

“Try to remove yourself from the awards and hoopla too,” says Grossfeld, referring to the Pulitzer Prize. “The scandal sells, but I think the real people that are the giants in this industry are beyond reproach because they are so honest and caring.”

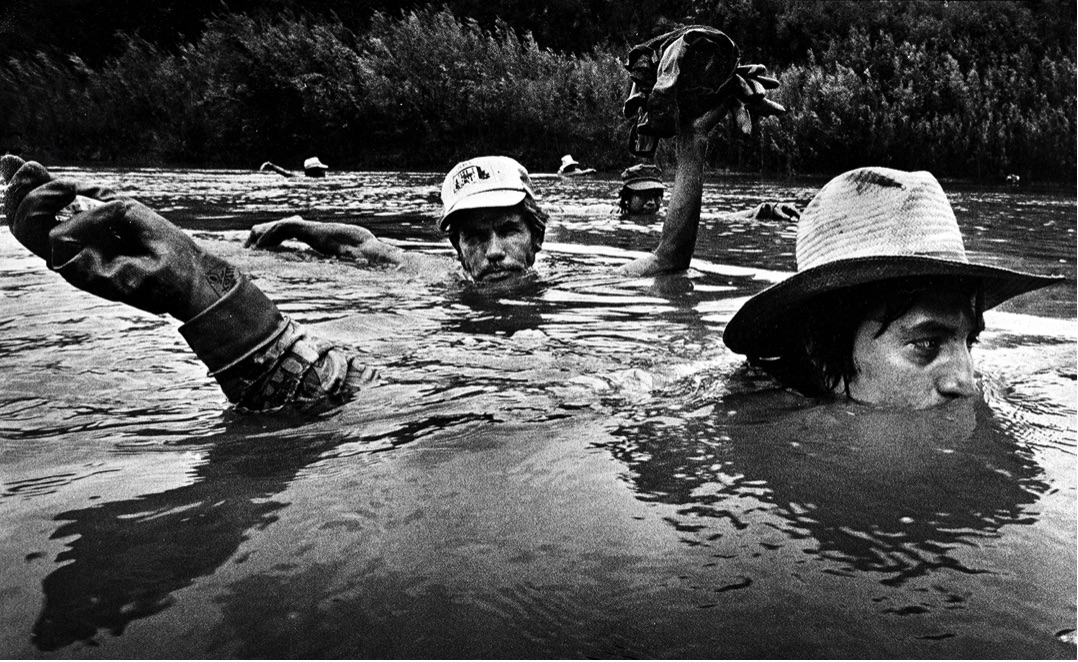

Cover photo: Migrant workers cross the Rio Grande River. Credit: Stan Grossfeld.

- Emily Atkin is pissed off about climate change. Her new newsletter Heated says we all should be - October 1, 2019

- How to grow your brand as a photojournalist and commercial photographer - August 1, 2019

- Six digital skills all new journalists should consider learning and a road map to unlocking them - July 15, 2019