Why understanding what it truly means to be digital is critical for long-term success

The second in a series of posts. You can read the first post here.

My favorite interview question to ask job candidates is, “What do you think it means to be digital?” The answer reveals a lot about how the individual thinks about being a journalist today.

The goal of every great journalist is to find a way, despite any obstacles, to reach their audience. Today’s journalists must understand that we are not defined by a platform — be it print, broadcast, web, or social — but rather that our goal is to reach an audience, whatever platform they choose to be on. Because so many of our platforms are increasingly digital, we have conflated doing digital with being digital.

So, what does it mean to be digital today?

Traditionally, “digital” is a platform classification reserved for those involved on the periphery of news gathering (doing digital), whether in social media, product, design, development, or analytics. This is the result of the decision publishers made to replicate their print operations for a digital world, rather than create new workflows that better reflected digital realities.

Fortunately, we now increasingly understand that digital is not a platform, or a department, or a priority. Rather, it is a philosophy focused on putting your user first.

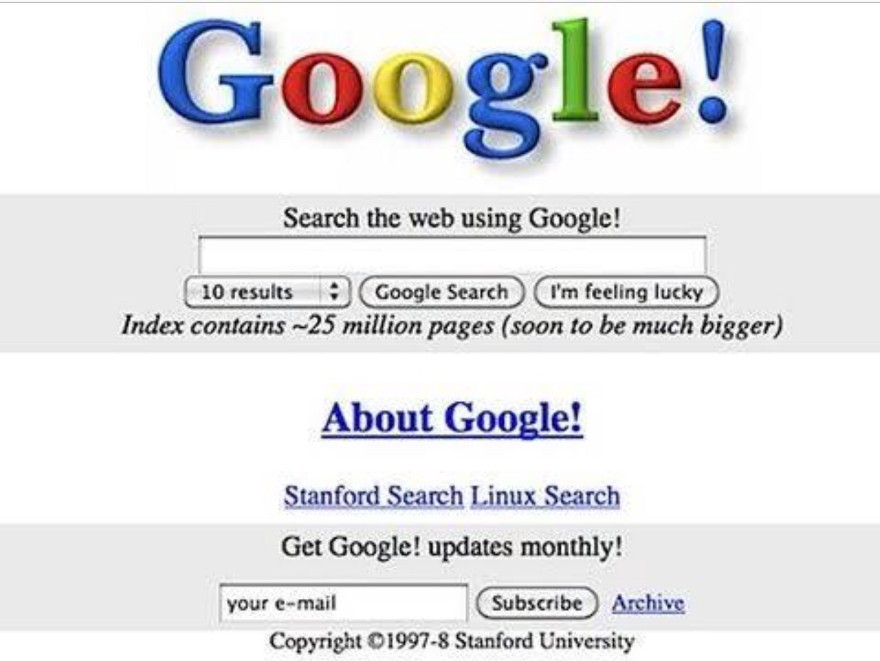

A great example of this digital philosophy in action is Google’s homepage. If you visited Google.com’s homepage when it launched, you would see that it looks quite different than it does today.

And yet, most people would be hard-pressed to identify a time when Google re-launched its homepage. That’s because over 20 years, Google has iterated the page incrementally to optimize it for their users. Their goal is to make Google more accessible and useful around the world. They’ve put their users at the centre of their decision-making conducting A/B tests continuously. Asking questions like, “Will increasing the size of the search bar by x result in more people doing searches?”

If so, then Google would refresh the design of the homepage.

This iterative approach puts users at the centre of all decision-making. It wasn’t done for altruistic reasons; it is also a cheaper approach to product launches. Instead of spending millions of dollars to launch something that could immediately fail, digital organizations approach their work through the ‘MVP: Minimum Viable Product’ lexicon popularized by Eric Ries in The Lean Startup. This means putting something out that’s good enough, learning from users what works and doesn’t, then iterating and improving until it works.

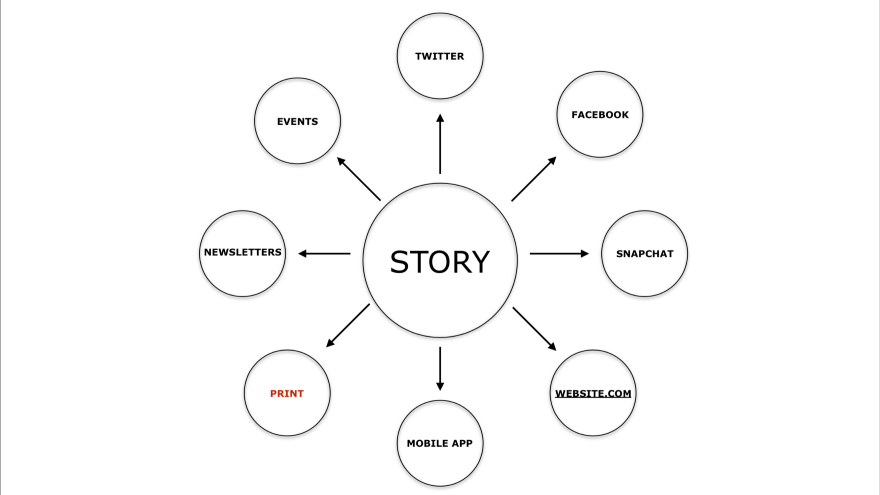

Journalistically this means defining your editorial and product strategy not by a platform but by the stories, topics, and questions that you choose to pursue for your community, then optimizing those stories for their desired platforms, listening to your readers and adapting.

A recent example of this approach was the reporting on the Trump Foundation conducted by the Washington Post’s David Fahrenthold in 2016. As outlined in the Nieman Lab for Journalism at Harvard University*, Fahrenthold was having trouble finding evidence of Donald Trump’s charitable donations. He turned to crowdsourcing through Twitter and the social media dialogue resulted in a series of print and online stories that ultimately played a role in Trump’s decision to shut down the foundation.

Whether intentionally or not, Fahrenthold understood that the best way for him to tell the Trump Foundation story wasn’t primarily through written articles. In this instance, it was through opening up the journalism to the community through another platform.

Approaching your editorial and product strategy this way changes the questions that you ask upfront. The question is then twofold. First, what is the story? Second, what is the best way for me to tell that story, be it on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Youtube, online or in print?

For the most part, content’s relevance originates at the story level, not the platform level. Politicos don’t care about whether they’re reading about Donald Trump’s Presidency in print, on a tablet, or on Twitter. They just want the Washington Post to continue its coverage.

This doesn’t mean that all original journalism should be outsourced to third-party platforms. Sometimes, a story may best be told in a 30-second video exclusively on Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram. Sometimes a story is best told in 1,500 words only in print or on the website. Sometimes, a story may work for all platforms. This is why having a team of specialists, comprised of social media, analytics, design, photo, video, and SEO experts, who can help you understand how to present, program, and edit the journalism, is so critical.

One misconception this creates is that you’re now giving away all of your journalism and intellectual property to third-parties for free. This is dependent on the types of business model your organization pursues. If you’re a subscription business, then distributed journalism should be considered an acquisition expense. If you’re an advertising business, then distributed journalism should be considered a scale and impressions play.

Above all, it’s about relevance. For most organizations there is very little overlap in audiences across the platforms. Reaching more audiences increases overall relevancy, allows for new opportunities and revenue streams to surface, and is tremendously exciting for anyone who cares about journalism and the role it serves in our communities.

The thornier question is how to financially support this approach to journalism.

On the revenue side, a story-centric approach opens up new avenues for business model innovation. Today, because of the historical precedents described earlier, most revenue teams approach their revenue opportunities at the platform-level.

Print sales team sells ads for the printed product, digital sales teams do the same for online, and circulation teams sells subscriptions to the print (and sometimes digital) product. Trying to capture revenue through all these platforms individually is expensive and makes it very hard to pivot. If any new platforms arise, the publisher has to hire, train or build out a sales or circulation team to capture revenues from that specific platform.

This limits an organization’s ability to continually transform their business based on user habits and market opportunity. Yesterday’s MySpace is today’s Twitter. Today’s smartphone is tomorrow’s voice-activated home system. If an organization overcommits its workflows, production, and revenue teams to any one platform, it limits their ability to pivot on to the next platform when it invariably arises.

Aligning workflows with stories or topics instead of the platform allows sales and circulation teams to sell integrated sponsorships and subscriptions around those stories and topics, not limiting them to selling ads or paywalls adjacent to the content on specific platforms.

A publisher’s combined print, tablet and website audience on a daily basis pales in comparison with their potential reach across all platforms. This creates a market opportunity for advertiser and consumer revenue. The more that a brand is in the discourse, the more opportunities for a value-exchange with customers can exist, centered around topic and question-specific revenue streams. Perhaps an ongoing topic such as the Trump Foundation reporting by the Washington Post could result in a sponsorship deal around a weekly newsletter on the issue, or a sponsored speakers forum on the topic? Display ads in tablet, print and on the website? Or maybe it results in a paid niche product or a pay-walled content strategy?

When the reader is at the center of decision-making it allows for more testing around new models at a fraction of the cost of launching new platform specific businesses.

My first job in journalism was in radio news. My second and third jobs in journalism were in television news. My fourth job in journalism was on a website and my fifth job in journalism was in print. In all those jobs I’ve tried to reach the right people with quality journalism in order to educate, inform and influence their communities, or public policy when required. It didn’t matter to me which platforms I had to learn. What always mattered was understanding where my audience lived, and how I could reach them.

I used to think this way as an individual journalist, and I believe the same mantra applies to news organizations. In my next post, I’ll attempt to work through how organizations could find sustainability, and even profitability, in the current journalism landscape.

*Full disclosure: I was a 2012 Nieman Fellow and have contributed to their publications.

This post originally appeared on Medium.