Four Tips on Gamifying Journalism From Al Jazeera’s Juliana Ruhfus

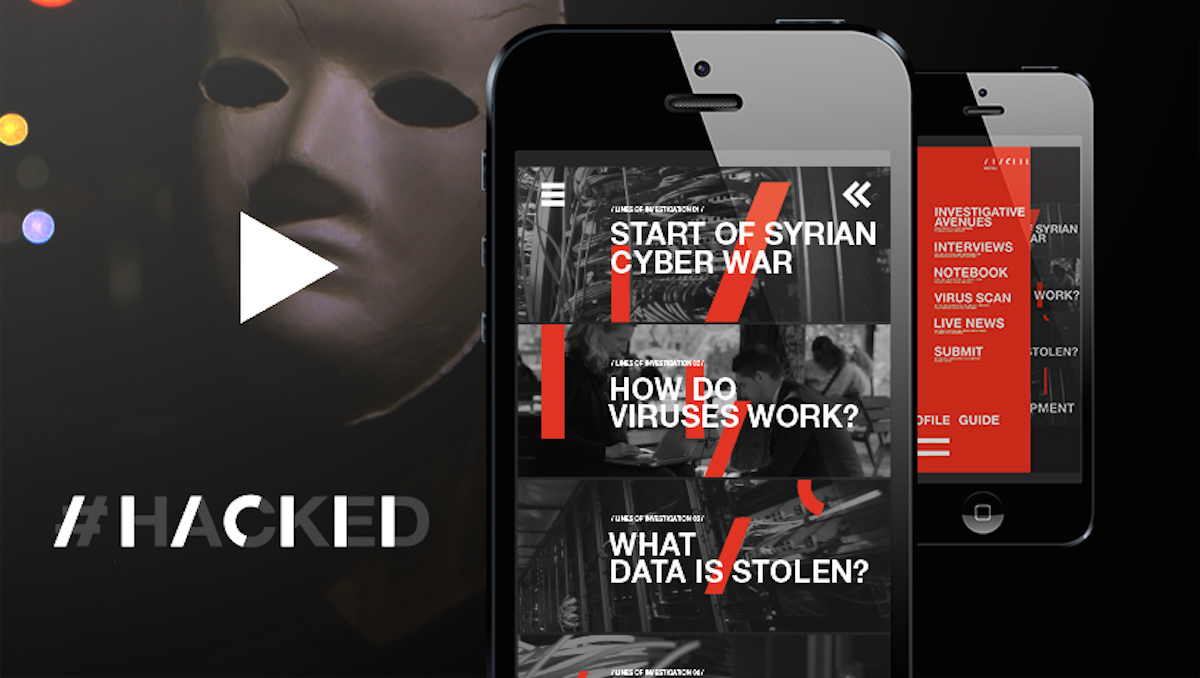

Last summer, Al Jazeera English’s People & Power program aired an investigation called “Syria’s Electronic Armies” about the men and women fighting for control in the country’s information war. Today, that investigation re-launches as an interactive mobile app called #Hacked.

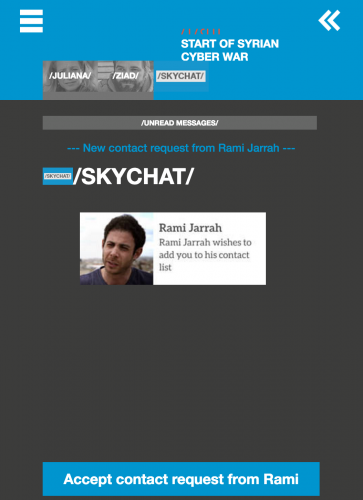

The news game, which is modeled after a messaging platform, challenges users to collect data on a cyber conflict while protecting their sources. Information is gathered by watching footage from the original investigation as well as exploring websites and social media accounts of real-life hackers in the Syrian conflict.

The news game, which is modeled after a messaging platform, challenges users to collect data on a cyber conflict while protecting their sources. Information is gathered by watching footage from the original investigation as well as exploring websites and social media accounts of real-life hackers in the Syrian conflict.

The decisions facing players — whether or not to pay hackers for information, when to go undercover, and whether or not to open files that could be infected with malware — mirror those faced by People & Power’s senior reporter Juliana Ruhfus, who led the investigation last summer.

But if recreating the world of an investigative journalist felt natural for Ruhfus, navigating the ethics of news gamification required an entirely new skill set.

“Part of the thinking process was, is there a danger at any stage that the game mechanics become so dominant that it will kill the journalism?” she said.

Storybench sat down with Ruhfus to talk about gamifying an investigation without compromising journalistic principles.

1. Make interactions meaningful

#Hacked wasn’t Ruhfus’s first experiment in news gamification. Two years ago, her team debuted the award-winning interactive investigation Pirate Fishing, which delves into the lives and practices of illegal fishermen operating in Sierra Leone and was co-developed with Italy’s multimedia production house Altera Studio.

While the response to Pirate Fishing was overwhelmingly positive, Ruhfus said one of the biggest lessons from the project was the need to develop consequences of user interaction.

“I wanted to do something with a clear sense of where you succeed and where you fail,” she said. “The choices in Pirate Fishing weren’t meaningful because the gamification didn’t change the outcome of anything. I think in general, this is what interactive projects don’t do enough of. We give people interaction but their click doesn’t mean anything.”

“With #Hacked, we wanted to make people think, because that’s the beauty of introducing game elements. Rather than just being a passive consumer, you think about a choice that you’re making and the consequences. If you were to just watch the film, I don’t think you’d ever look at it that way.”

Because #Hacked users take on the role of an investigative reporter, their choices lead to real-life penalties for compromising source confidentiality, failing to run virus scans and placing trust in the wrong sources.

“As a journalist, for example, you have to consider whether you can accept the terms of the interviewee,” Ruhfus said. “At what point do you say no because your journalistic integrity and freedom is compromised? The users and players of #Hacked will also have to consider what choices they make to gain access or lose access to information.”

“But we also wanted to make all the information accessible and for people to learn as much about the cyber war as possible. We talked a lot about winning and losing, and we ultimately came up with two metrics — data and time — so you have to collect the maximum amount of data,” she said. “If you make the wrong choices and are too lazy to watch background videos, then you don’t collect data. You can also face time penalties if you have to double back and redo a part of the investigation.”

2. Define your rules

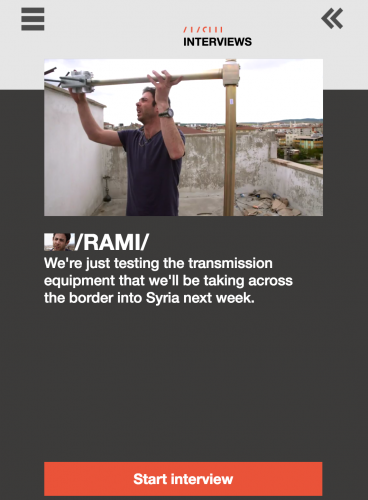

To introduce users to “Black Hackers” and local fixers, Ruhfus had to work from textual documents and her own knowledge of how reporting missions unfold. But in order to preserve the game’s integrity as a piece of journalism, she also needed a set of clear-cut rules for distinguishing between reality, fiction and the conditions of the game.

“I felt that at some stage, it wasn’t intuitive what was real and what was not real,” she said. “Some of the real characters, like Peter Fein from Telecomix, seem so off the wall because he’s an activist that’s trading cat pictures. You find out about a group that’s published a hack revealing how American surveillance technology was used by the President Assad government and realize you’re also dealing with a guy who’s trading cat pictures.”

“Everybody thinks, ‘well surely that must be fiction, you guys are ridiculous and now you’ve taken the game a bit too far’, but this was real. And then you have characters like your local producer or academic, and they’re totally straight and everybody presumes they are real. It was a whole problem of fact being stranger than fiction.”

Ruhfus drew the line between fact and fiction by teaming up with John Lau, a postgraduate student from the National Films and Television School School’s Games Design course, who helped her develop a set of in-game and out-of-game rules.

Ruhfus drew the line between fact and fiction by teaming up with John Lau, a postgraduate student from the National Films and Television School School’s Games Design course, who helped her develop a set of in-game and out-of-game rules.

“Everything that’s taking place in the messages is an in-game experience, and all the in-game talk is 100% strict journalism plus the hacks,” Ruhfus explained. “And then we have out-of-game, which is actually the notifications and the messages that we send. Those will tell you about what the rules of the game are, how you waste time, what you should’ve done differently.”

“For me personally, the achievement that everything in it is journalism is immense. Every hack in the app is based on a real hack that has taken place. When you read texts from hackers, those have been taken from court documents. When you look at the social engineering on how we’re trying to come at you, how we’re creating an avatar that’s enticing you to click on something, that’s what has happened during Syria’s cyber war.”

In order to stick to her in-game and out-of-game guidelines, Ruhfus had to kill some darlings. She vetoed technically impressive hacking simulations to follow her rule that all linked websites and social media accounts must be real. She also introduced greater transparency about which characters were entirely real and which were fictional, but based on her investigation. The only exception is her own character, who sometimes crosses the boundaries between the two when giving feedback and guidance to users.

“For me, the biggest learning process was that if you establish really clear gaming rules, then that really resolves the fact and fiction thing. By separating the in-game from out-of-game communication, it suddenly went back to being journalism,” she said. “I would think about rules the whole time.”

3. Seek feedback early and often

Finding sounding boards at each stage in the process helped Ruhfus navigate the ethical challenges of gamification. When developing fictionalized characters like the Black Hackers, she consulted “White Hacker” Ali Haider on building interactions that stayed true to reality.

“We were very lucky to work with Ali Haider. He has investigated a lot of the hacks during the Arab Spring and has first-hand knowledge, and he helped a lot keeping the hacks real. He would read through some of the scripts I wrote for the Black Hacker to make sure that it’s correct both factually but also that it feels right.”

After writing the message exchanges, Ruhfus sent her scripts to sources from the investigation for approval. She also solicited design advice from her target demographic: millennial audiences. Students from Birmingham University and City University, as well as the National Films and Television School, helped test the app and provided insight into game development.

“The best thing I probably did right from the beginning was I decided I would work with students from the National Films and Television School Games Design and Development course. From the pre-production to the final production and they had all these great ideas, and also they’re of an age and demographic that I’d like to reach,” said Ruhfus.

“My big lesson learned from Pirate Fishing is bounce it off people. That is the way I like to work now. Get feedback as you go along,” she said.

4. Build cheaply and fail fast

Ruhfus’s team was able to put #Hacked together in approximately three months using Conducttr, a tool for integrating interactive storytelling and gaming.

“My goal is to do things cheaply and quickly, so we learn fast, fail fast. Because everything is moving so quickly and there aren’t any templates or models, I think it’s really important that we learn from our mistakes and keep reinventing new formats until we hit on something that works,” Ruhfus said. “I also wanted to do something you could use on mobile, and Conductrr ticked all of those boxes.”

Read more about the building of #Hacked from Juliana at Medium.

This post has been updated to correct the spelling of Conducttr.

- Four Tips on Gamifying Journalism From Al Jazeera’s Juliana Ruhfus - October 4, 2016

- Tips and Tutorials from London’s Journocoders Meetup Group - September 1, 2016

- How one digital humanist visualized the shapes of 50,000 novels - August 10, 2016