Telling the story of plastic bags, plastic forks and “microplastics” polluting our planet

“The average plastic bag is used for only 12 minutes before it is discarded,” writes journalist Konstantin Kakaes in “A Hundred Million Invaders,” a project on plastic pollution published today by NY/NJ Baykeeper, a conservation organization dedicated to protecting the New York-New Jersey harbor and estuary.

And much of that plastic ends up as floating debris bobbing along the New York Harbor, Kakaes writes, his text accompanied by animated illustrations designed by Joe Alterio and Tim Lillis of Primer Stories . The Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation funded the project.

With “A Hundred Million Invaders,” Baykeeper partnered with Groundsource, a text messaging platform to start a conversation with the communities affected by the plastic pollution in New York and New Jersey’s waterways. Baykeeper helps citizen groups to help protect and restore the waterways. The idea is that Groundsource will help them recruit more people to the cause while raising awareness of the pollution. But to launch the project and tell the story in a compelling way, Baykeeper asked the Dodge Foundation’s Molly de Aguiar for help finding someone to lead the project’s design and art direction. Alterio and Lillis were then brought on.

Storybench spoke to the three of them to understand how the project was pulled off.

How did Dodge find Primer Stories and what kind of story did you want to tell for Baykeeper?

Joe Alterio and Tim Lillis: Molly from Dodge had taken notice of what we were up do and had been complimentary to us on Twitter about a story we had published. After reading a bit more about her and her strong advocacy for new medium exploration in service of communicating important ideas, we reached out. We had a great few conversations and found we were aligned in many ways about the potential for web storytelling, and she offered to work with us and another of Dodge’s clients, Baykeeper, to see if something could be created in collaboration.

Dodge knew they wanted to use Groundsource’s technology to be able to connect readers with Baykeeper’s cause. There’s no doubt that a piece chronicling Baykeeper’s activities would be great, highlighting the important work they are doing, but if we didn’t provide a way to connect with the folks who’ll be reading it, it would be a missed opportunity. There’s no better time to call folks to action then when they are actively engaged in a topic — the knowledge is fresh, and so is the outrage. In terms of visuals that that they were looking for, there were no specific requests, but the goal of creating a compelling immersive experience that was in line with Baykeeper’s values was certainly top of mind.

Dodge knew they wanted to use Groundsource’s technology to be able to connect readers with Baykeeper’s cause. There’s no doubt that a piece chronicling Baykeeper’s activities would be great, highlighting the important work they are doing, but if we didn’t provide a way to connect with the folks who’ll be reading it, it would be a missed opportunity. There’s no better time to call folks to action then when they are actively engaged in a topic — the knowledge is fresh, and so is the outrage. In terms of visuals that that they were looking for, there were no specific requests, but the goal of creating a compelling immersive experience that was in line with Baykeeper’s values was certainly top of mind.

Molly de Aguiar: I have clearly witnessed through our Arts Education work at Dodge that people learn in many different ways. Some kids who think they’re no good at math, for example, will have breakthroughs when taught math concepts by using dance or music techniques. So while a person may have trouble comprehending issues around microplastics by reading an article about it in the newspaper or on a website, what if they were told a memorable story, with memorable visuals to help them understand? Or a story that simply captures their attention better and results in deeper comprehension?

I’m interested in the intersection between sharing more power with the community – building something with them, not for them, as LaurenEllen McCann would say – and using creative engagement and storytelling to make the work even more impactful. That’s why I invited Primer Stories into the already fruitful partnership between GroundSource and Baykeeper. In terms of the kind of story I wanted to tell, I guess I’d say that it wasn’t really about what I wanted – it’s what would be most powerful for Baykeeper to advance their work. But I will say that I love good visual design and I take every opportunity I can get to work on creative design projects. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”says @mollydeaguiar”]Good design is dramatically underrated and underused in the nonprofit sector[/inlinetweet]. I believe it has tremendous power to advance our missions.

How did Primer start planning, sketching out and then building a story as complex as this one?

Alterio and Lillis: As we immersed ourselves in Baykeeper’s mission, it quickly became evident that some on-the-ground reporting would be essential in telling the story properly. We were fortunate to be introduced to veteran journalist Konstantin Kakaes, and we talked with him quite a bit about story ideas and the tone of the piece — how do we give a broad view to include enough context of the past and future of plastic without obfuscating the work of Baykeeper, and still allowing space for a call to action for readers.

With Konstantin’s first draft in place, we were able to hit the ground running and begin to fill in some of the blanks. Using his act structure as a guide, we broke the story into visual “scenes” as a film director would, and began iterating in earnest. We always start by trading pencil sketches internally and choosing the ideas that generate the best possible narrative, leveraging visuals to go beyond what the words are saying. The images should complement the copy, but also tell a story all their own.

This project, with its interactive aesthetics and long roster of producers, must have taken months and considerable funding to complete. What can you tell us about how much it cost and the challenges it faced?

De Aguiar: The project wasn’t as big, perhaps, as you might think. The real challenge was trying to get it done while also juggling all of the other things on our to do lists, including Joe and Tim’s new season of stories (revolving around the theme of “change”) at Primer Stories. I think we kicked off the project late last summer in August or September. The first order of business was finding a science journalist who could work with Baykeeper to tell the microplastics story in a compelling way, which I think Konstantin Kakaes did beautifully.

Once we had a text draft of a story and went through a couple rounds of edits, Tim and Joe got to work on developing the visual story. At some point, we also had a discussion about integrating GroundSource into the story, to give people a way to take action if they felt inspired. We went through a few rounds of edits on the visual stories, and then we spent some time thinking about how to share it with the world before finally unveiling it to the public. All in all, I guess it took about five months, and it cost less than $20,000, which Dodge paid for.

Can you give us some insider tips on how you designed one or more of the illustrations?

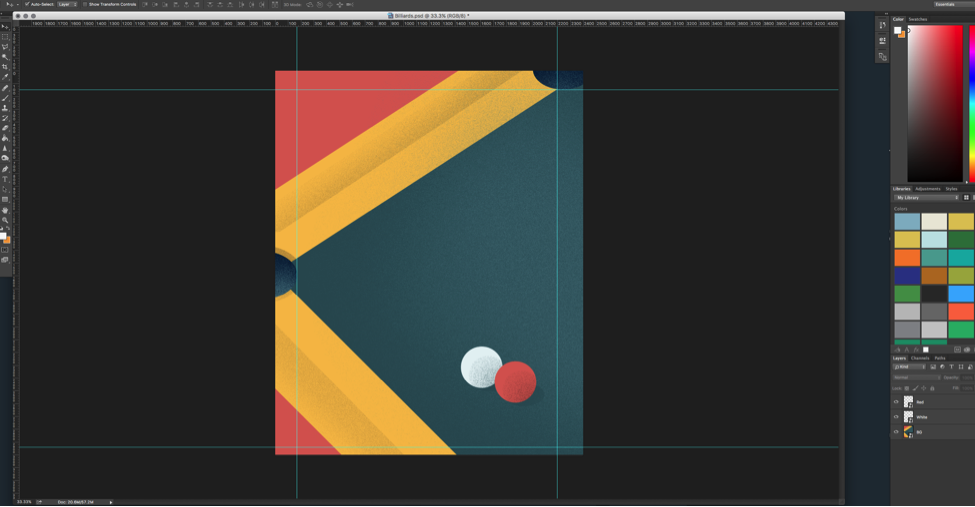

We use a mix of AI, PS, and AE to make most of our graphics. For the billiards gif, we made the elements in Photoshop:

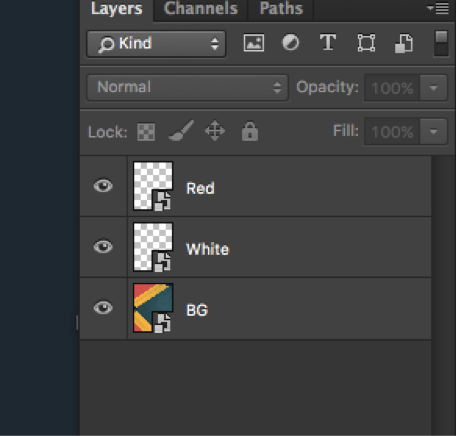

Making sure to create a set of smart objects that and a background that have no top-level layer styles on them, as that would confuse an AE import:

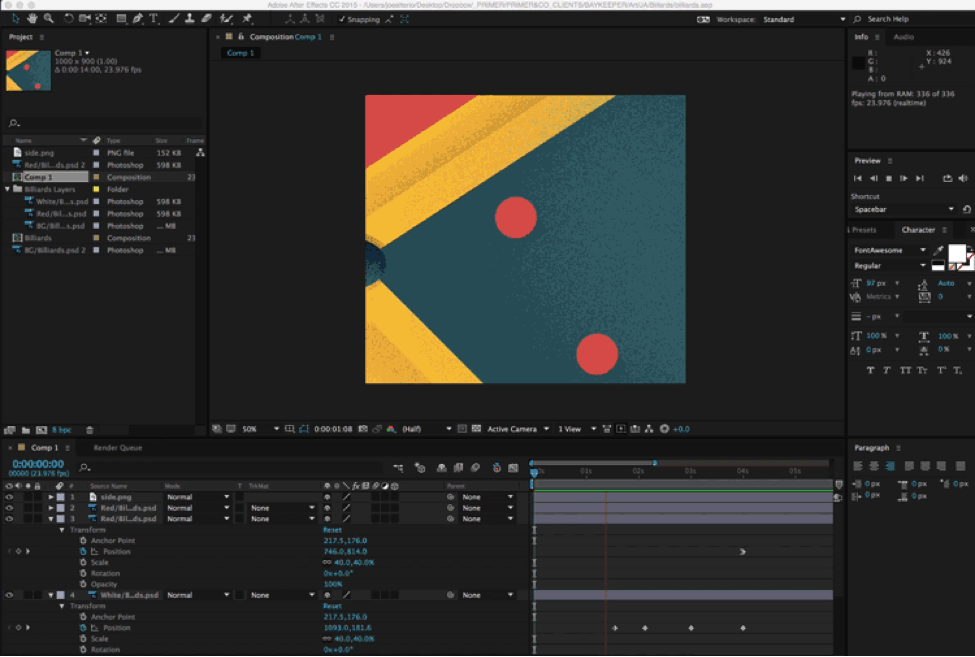

Then, we bring each piece into AE as footage, and animate in AE, making judicious use of the Easy Ease function to replicate that momentum of the billiard balls just right.

It took a while to get physics looking correct. Then, we export as a .mp4, a small enough size so that it’s usable on the web. For the mobile breaks, we used Gifrocket to convert the mov to a gif:

What advice do you have for people who want to approach a foundation like Dodge for help telling a similar story?

De Aguiar: I would encourage nonprofits who want to tackle more creative storytelling to sit down with their existing funders and have an honest conversation about the costs associated with better communications – that it requires extra dollars to test some ideas and formats. Philanthropy can play an extremely valuable role in providing experimental dollars to nudge nonprofits to try new things. And we as funders should not expect grantees to take the money out of existing budgets. Baykeeper would not have taken the money out of their budget to partner with Primer Stories.

I would also encourage nonprofits to start building more communications dollars into their proposals, and call it out in their proposals, while also continuing to have one-on-one conversations with funders. Taking these steps would help elevate the awareness and importance of funding good storytelling.

How has Primer Stories grown and what’s next?

Alterio and Lillis: Our ever-expanding cast of contributing writers has certainly helped us reach new audiences. The topics they write about, and their perspectives, help ensure that there truly is something interesting for almost everyone on our site. As a result of our track record of giving a broad range of topics custom treatments, each their own, we’re getting a lot more readers who are thinking about new ways to tell their stories. We’ve talked with an equally broad range of potential clients, and whether it’s folks in sustainable food, healthcare, the arts, government, tech services, activism, aerospace, or another field, our thought when we started Primer Stories bears out — people want unique, authentic web experiences that make the best of what’s possible on the web today.

To that end, what’s next for us is really cultivating relationships under the banner of Primer & Co. where we team up with organizations to tell their stories artfully, with visuals that reinforce and enrich the story, enabling better experiences for readers. They know their audiences expect a lot from them, and they want to create beautiful narratives that respect the intelligence of their readers. All this means that the Stories side of the project has become more of a display case to show our wares, while the studio side is how we pay the bills. We’re still committed to making ad-free interactive awesomeness for our audience, and we’ve got a bunch of great projects that will be rolling out over the next few months; everything from a game about climate change and time travel to more videos and one-offs. And of course, we’ve starting to plan Season 5. (Also, we’re hiring! If you’re a developer, designer, or project manager who is interested in what we’re doing, please reach out to us.)

This post has been updated to correct the cost of the project.